Archaeologists have found menorah artifacts and Hebrew inscriptions that may prove a 4th-century church was actually a Roman-era synagogue.

Archaeologists in southern Spain have uncovered compelling evidence suggesting that a Roman-era building—long believed to be an early Christian church—may, in fact, have been a synagogue serving a small, now-forgotten Jewish community. The discovery, made in the ancient Ibero-Roman town of Cástulo near modern-day Linares in Andalusia, could represent one of the oldest known synagogues on the Iberian Peninsula.

The findings were made during ongoing excavations led by Bautista Ceprián and his team from the Cástulo Sefarad Primera Luz project, which is dedicated to uncovering traces of Jewish history in the region. While the building had originally been classified as a 4th-century Christian basilica, a growing body of archaeological evidence now challenges that assumption.

Artifacts Tell a Different Story

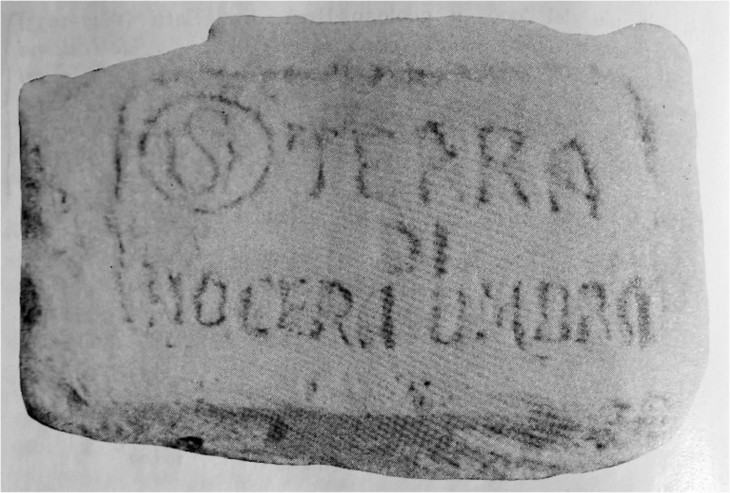

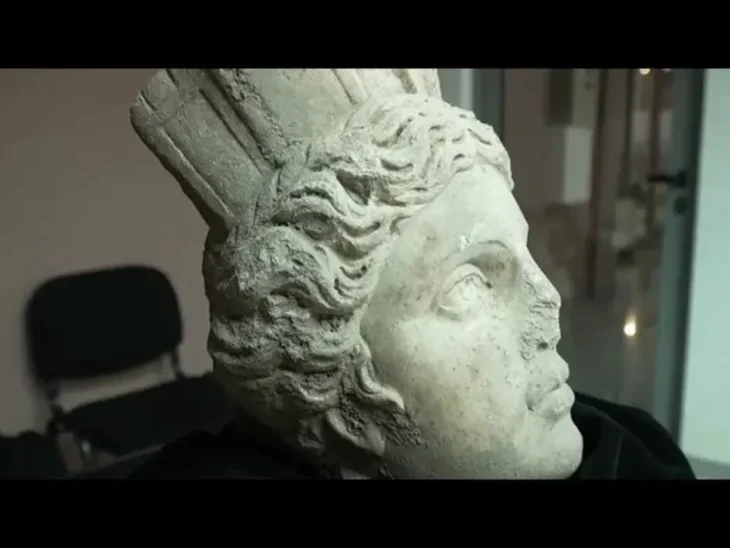

The breakthrough came with the unearthing of several artifacts: three oil lamp fragments adorned with seven-branched menorahs, a roof tile featuring a five-branched menorah, and a piece of a conical jar lid inscribed with Hebrew text. Experts remain divided over the translation—some suggest it reads “light of forgiveness,” others interpret it as “Song to David”—but all agree that the inscription signals the presence of a Jewish population previously undocumented in historical records.

“We first found the roof tile with the five-branched menorah during excavations in 2012–2013,” said Ceprián. “But only now, with the addition of these recent finds, are we able to suggest that a small Jewish community likely lived here.”

📣 Our WhatsApp channel is now LIVE! Stay up-to-date with the latest news and updates, just click here to follow us on WhatsApp and never miss a thing!!

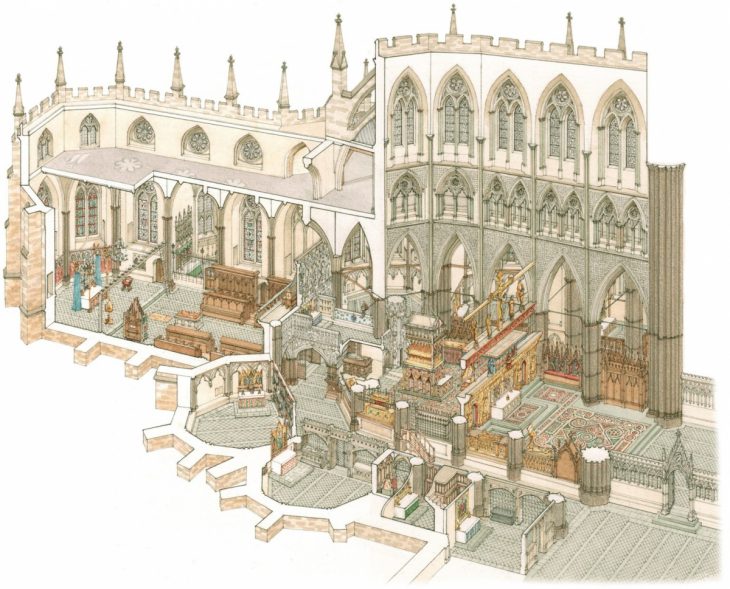

Architectural Clues Align with Synagogue Design

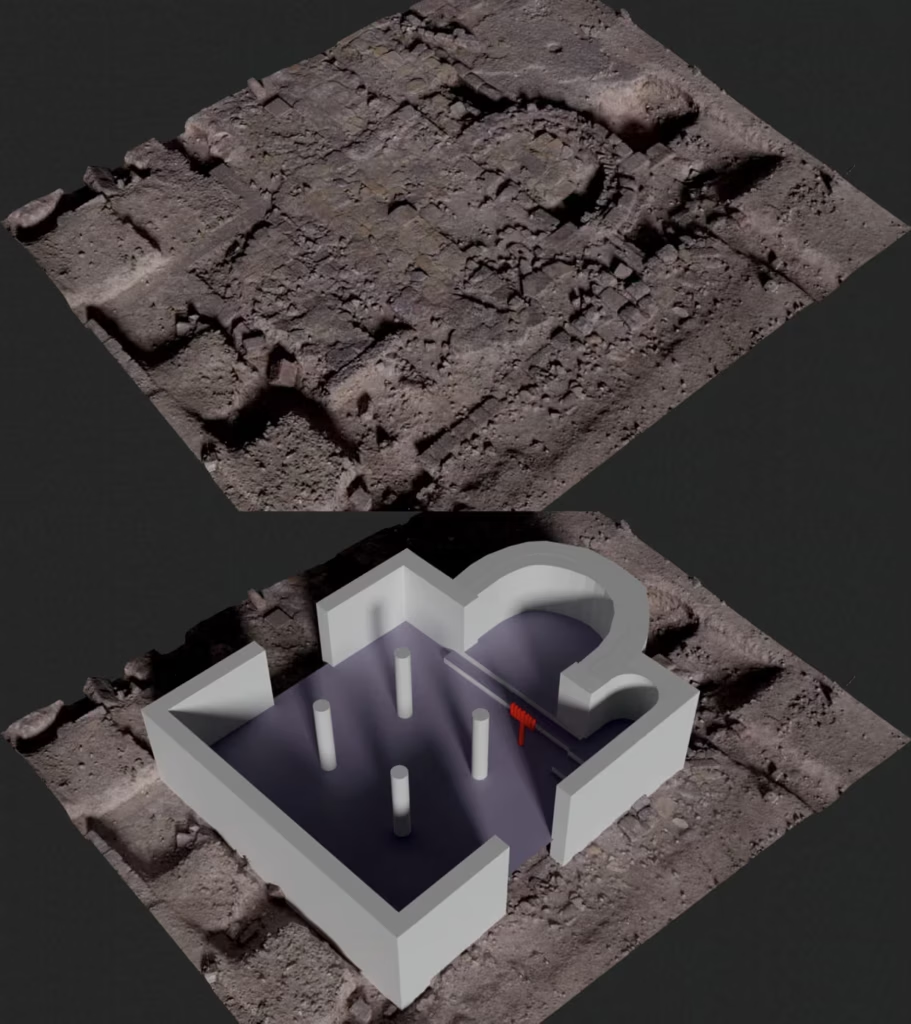

In addition to the artifacts, the building’s structure further supports the synagogue hypothesis. The layout is squarer than the elongated design typical of early Christian churches. At its center, archaeologists identified the foundations of a raised platform—likely a bimah, used in Jewish worship for Torah readings—rather than the apse-centered layout of Christian liturgical spaces.

One notable feature is a possible socket where a large menorah may have once stood, and the absence of tombs within or near the building is especially telling. Early Christian churches often included burials, but Jewish religious law forbids burial within close proximity (about 23 meters) to residential or religious structures.

“The absence of Christian iconography, relics, or human remains inside the structure contrasts sharply with other confirmed Christian sites nearby,” Ceprián noted. “This, combined with the menorah-decorated artifacts, leads us to believe the building functioned as a synagogue.”

Location Offers Additional Insight

The site’s location on the outskirts of the ancient city, near a now-defunct Roman bathhouse, offers additional context. In the 4th and 5th centuries, bathhouses were often regarded by Christians as remnants of paganism—spaces to be avoided or even demonized. This positioning could have offered a discreet, less-traveled area suitable for a minority religious group practicing in a dominantly Christian environment.

Interestingly, Ceprián suggests that local bishops may have deliberately allowed the synagogue’s proximity to the former bathhouse to link Judaism with pagan practices—possibly to discredit the Jewish faith as Christianity’s influence expanded.

A Silent Community in the Historical Record

Despite the physical evidence, one glaring omission remains: there are no known written records mentioning a Jewish community in Cástulo. This gap has led scholars to proceed with cautious optimism.

“We acknowledge the criticism and questions that may arise from the lack of textual corroboration,” said Ceprián. “But the evidence we’ve uncovered—architectural, symbolic, and material—strongly supports our hypothesis.”

Some historians speculate that the community may have vanished under social or religious pressures. Unlike other regional towns listed in anti-Jewish legislation by Visigoth King Sisebut in the early 7th century, Cástulo goes unmentioned—suggesting its Jewish population may have dissolved or dispersed long before.

Broader Implications for Iberian Jewish History

If definitively confirmed, the Cástulo synagogue would be among the earliest on the Iberian Peninsula, predating the more famous medieval synagogues in Toledo, Córdoba, and Girona by centuries. The most recently discovered synagogue in Andalusia, located in Utrera, dates to the 14th century—over a millennium later.

Professor Elisa Morera of King Juan Carlos University in Madrid called the discovery “extraordinary,” noting that it confirms a deeper, older Jewish presence in Spain than commonly understood.

Looking Forward: Preserving a Forgotten Past

Excavations at the site are ongoing, and the team hopes to open it public in the near future. Ceprián and his colleagues believe further research could reveal even more conclusive evidence—and perhaps shed new light on the daily life, worship, and eventual fate of the forgotten Jewish community of Cástulo.

“At its core, this is a story of coexistence—however brief—and of a lost voice in Spain’s diverse historical tapestry,” Ceprián said. “As we continue digging, we’re not just uncovering stones—we’re recovering memory.”

Expósito Mangas, D., Ortega Díez, J. C. & Ceprián, B. (2025). Una posible sinagoga tardoantigua en Cástulo. Estudio del Edificio S de la ciudad. Vegueta, 25(2). https://doi.org/10.51349/veg.2025.2.17

Cover Image Credit: Francisco Arias