An 8,500-year-old micro-carved bead and a 10,000-year-old skull room uncovered at Sefertepe reveal a remarkably complex symbolic world in Neolithic Anatolia.

When archaeologists returned to Sefertepe for the 2025 field season, few expected that two of the smallest objects uncovered—one carved into a pebble-sized bead, the other into a modest limestone block—would upend assumptions about the symbolic imagination of early Neolithic communities. Yet on a low rise overlooking the plains of Viranşehir, the easternmost edge of Türkiye’s vast Taş Tepeler region, a pair of faces and a room filled with ancient skulls have pushed Sefertepe into the center of scholarly attention.

Situated roughly 10,000 years ago within the Pre-Pottery Neolithic landscape, Sefertepe has often stood in the shadow of its monumental neighbors: Göbeklitepe’s towering pillars, Karahantepe’s sculpted chambers, and Sayburç’s enigmatic reliefs. But recent discoveries show that Sefertepe’s significance lies not in architectural grandeur, but in the meticulous, intimate symbolism crafted into its stones, beads, and mortuary practices.

A Stone Block with Two Stories to Tell

The first major discovery of the season emerged from a partially exposed terrace wall: a small stone block bearing not one, but two human faces. Although they sit side by side, the sculptor clearly intended them to be perceived differently. One face is carved in high, confident relief; the other in a shallower, almost ghostlike form.

At first glance, the difference may appear technical. But the excavation team quickly realized the stylistic contrast was deliberate. The two faces may represent separate identities, social roles, or cosmological states—perhaps even shifting statuses in life and death. Unlike the stylized heads found at Karahantepe or the abstracted expressions at Göbeklitepe, these faces show a more experimental aesthetic, suggesting Sefertepe nurtured its own artistic tradition.

📣 Our WhatsApp channel is now LIVE! Stay up-to-date with the latest news and updates, just click here to follow us on WhatsApp and never miss a thing!!

Their placement on a single stone invites interpretation. Were they meant to be seen together, as dual aspects of a single story? Or did the block once mark a threshold through which two symbolic realms intersected? For now, the stone keeps its secrets.

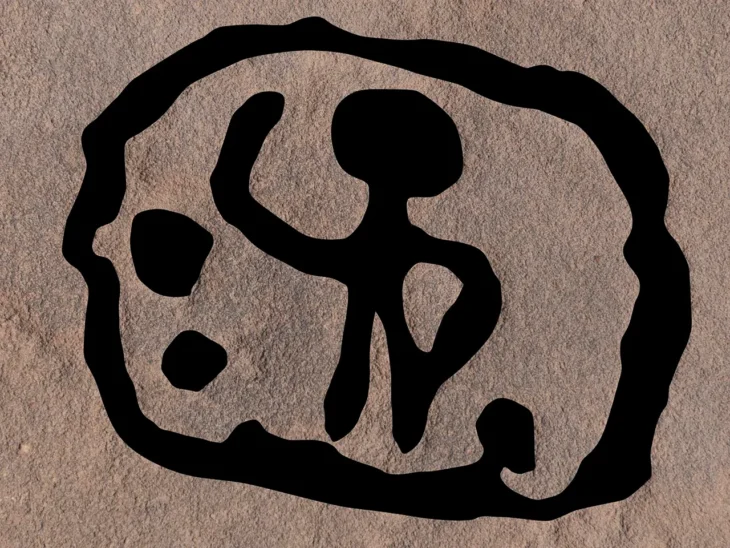

The Double-Faced Basalt Bead

If the twin-faced block introduces the season’s theme of duality, a far smaller artifact embodies it even more directly. Among the dozens of beads recovered this year, one stands out: a tiny, polished bead carved from dense black basalt, bearing two human faces—one on each side.

Such craftsmanship is extremely rare in the early Neolithic Near East. Only a few centimeters in size, the bead required remarkable precision to carve. Its presence raises immediate questions: was it worn on the body? Carried as a protective amulet? Passed between individuals during rituals?

Whatever its function, the bead reveals two crucial insights. First, Sefertepe’s artisans were as skilled in micro-carving as the region’s more famous builders were with monumental stone. Second, the community’s symbolic lexicon extended beyond architecture into personal ornamentation, hinting at the intimate, portable dimensions of Neolithic belief.

Other beads unearthed this season deepen this picture. Crafted from jade, labradorite, and limestone, several exhibit snake-head shapes, while others bear geometric incisions. Jade and labradorite are not native to the local geology, indicating long-distance exchange networks or wandering procurement routes. “Sefertepe’s bead assemblage clearly shows that this was not an isolated settlement,” notes excavation director Assoc. Prof. Emre Güldoğan. “People here were connected—and they expressed those connections in the materials they chose.”

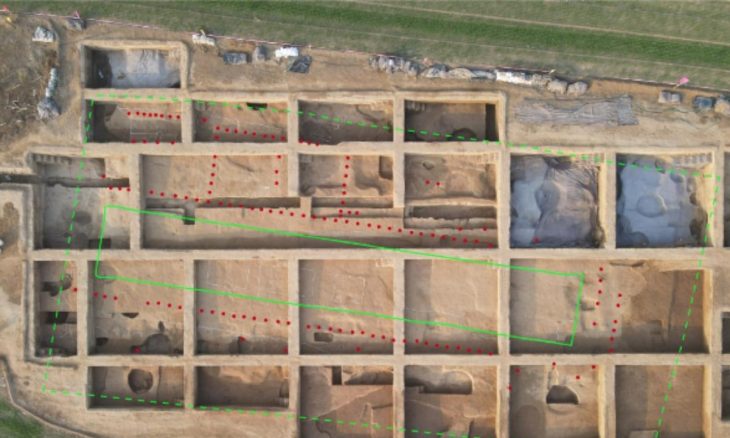

Inside the 10,000-Year-Old Skull Room

Yet the most haunting discovery lies not in ornament, but in death. During the 2024 season, archaeologists uncovered a small chamber where 22 human skulls had been deliberately placed. Most lacked mandibles, and no additional bones were found—signs of intentional selection rather than random deposition. The team named the space the “skull room.”

Just meters to the north, excavators encountered a contrasting mortuary pattern: seven skulls interred together with their full skeletal remains. The juxtaposition of these two burial modes suggests a layered ritual landscape in which skulls held shifting symbolic roles. Some individuals were curated long after death, their skulls gathered into communal memory spaces. Others were left intact, perhaps preserving familial identity or social belonging.

Across the Taş Tepeler region, human skulls often feature in symbolic architecture, but Sefertepe’s dual mortuary system appears unique. Here, fragmentation and wholeness coexisted. Selection and preservation coexisted. Memory and anonymity coexisted. The skull room, with its careful arrangement, may have functioned as a ritual archive—one that recorded ancestors not through writing, but through the human head itself.

A Settlement Defined by Subtlety

Viewed together, the season’s discoveries show that Sefertepe’s symbolic world operated at multiple scales. Reliefs carved into stone blocks conveyed layered meanings. Micro-carved beads embodied personal identity or ritual function. Human skulls, curated and arranged with intention, shaped relationships between the living and the dead.

Rather than standing in the shadow of its monumental neighbors, Sefertepe is proving to be an essential component of the Taş Tepeler cultural mosaic. It is a site where artistry was expressed through tiny, precise carvings; where ritual practice navigated the boundary between the individual and the collective; and where symbolism extended beyond enclosures into the objects people wore and carried.

As excavation continues, Sefertepe is expected to play a larger role in understanding the diversity of early Neolithic belief systems. Its micro-carved bead and its ancient skull room now stand as powerful reminders that some of the most profound expressions of meaning in the ancient world were neither the largest nor the most visible—but the most intentionally crafted.

As the Taş Tepeler project continues to map the world’s earliest ceremonial landscapes, Sefertepe stands as a reminder that Neolithic symbolism was not a monolith. It was a mosaic—one in which even the smallest object could carry the weight of two faces, two stories, and two worlds.

Cover Image Credit: Human face reliefs from Sefertepe. Republic of Türkiye Ministry of Culture and Tourism.