The quiet waters of Lake Mendota have concealed something far more sophisticated than a scattering of lost boats: archaeologists have now mapped 16 ancient dugout canoes, revealing a structured canoe-sharing system used by Indigenous communities thousands of years before the rise of cities in the Old World. New radiocarbon dates push the earliest of these vessels back 5,200 years, older than the Great Pyramid of Giza, making it the most significant prehistoric canoe cluster ever documented in the Great Lakes region.

A Prehistoric Transportation Hub Hidden Under Modern Madison

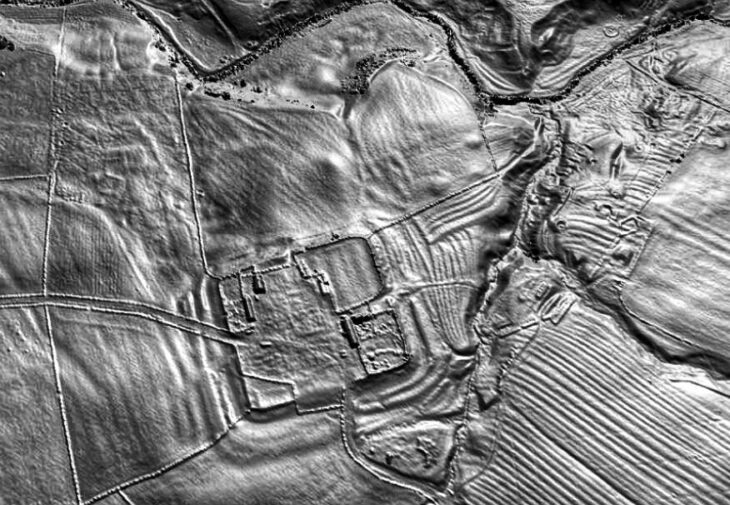

The concentration of canoes sits just offshore from a network of ancient Indigenous trailways that once crisscrossed the Madison isthmus. According to Wisconsin Historical Society maritime archaeologist Tamara Thomsen, the pattern is deliberate: this was not a random accumulation but a designated canoe cache, a place where travelers could leave a canoe and continue on foot or pick up another on their return.

“It’s a parking spot that’s been used for millennia,” Thomsen noted—an efficient, community-managed transport node that would put today’s bike-sharing systems to shame.

The cache sits within Lake Mendota’s western shallows, a section of the lake that would have been only about a meter deep between 7,500 years ago and 1000 BCE, when a long drought reshaped regional landscapes. For travelers, it was the ideal depth to bury canoes so they would remain waterlogged, preserved, and ready for reuse.

From One Discovery to Sixteen

The investigation began modestly in 2021, when Thomsen documented a remarkably intact 1,200-year-old oak canoe resting 24 feet below the surface. That alone would have been a landmark find—but a year later, a second canoe dated to 3,000 years ago was identified, lying directly above a 4,500-year-old craft. A 2,000-year-old vessel was found nearby.

📣 Our WhatsApp channel is now LIVE! Stay up-to-date with the latest news and updates, just click here to follow us on WhatsApp and never miss a thing!!

At that point, the time-stacked layering made it obvious that Mendota held something more elaborate than sporadic accidents.

Working with UW-Madison professor Sissel Schroeder, along with preservation officers from the Ho-Chunk Nation and the Bad River Band of Lake Superior Chippewa, Thomsen expanded the survey. The result: twelve additional canoes, each trapped in its own sediment pocket, forming a multi-period record of repeated, structured use.

Engineering Choices that Precede Written Science

Half the canoes were built from red or white oak, according to a wood analysis by the U.S. Forest Products Laboratory. Oak is not a random choice. Researchers now think Indigenous canoe builders deliberately exploited a botanical advantage: tyloses, the wax-like cellular growths that make wood more resistant to water and rot.

In white oak, tyloses occur naturally. In red oak, however, they appear when a tree is stressed or wounded—raising a bold hypothesis: ancient builders may have intentionally wounded red oak trees generations before harvest, effectively bioengineering superior boat timber long before modern forestry science existed. The canoe cache at Mendota may therefore preserve not only travel infrastructure but also a record of early applied botanical engineering.

Routes Toward Sacred and Economically Vital Landscapes

Archaeologists believe travelers using these canoes often moved toward Lake Wingra, home to springs considered sacred by the Ho-Chunk Nation. One spring is traditionally viewed as a portal to the spirit world. The transportation network connecting Mendota, the isthmus, and Wingra would have supported both spiritual travel and regional commerce.

“The canoes remind us how long our people have lived in this region and how deeply connected we remain to these waters and lands,” said Bill Quackenbush, Tribal Historic Preservation Officer for the Ho-Chunk Nation.

The find also raises the possibility that older vessels remain buried deeper in the lakebed. If drought-era water levels encouraged canoe caching, and if younger boats lie atop older ones, Thomsen argues a 7,000-year-old canoe may still be waiting beneath the silt—evidence of human presence that predates historically documented tribal groups.

Preservation Efforts and Federal Investment

Two of the recovered canoes are currently undergoing conservation. The Wisconsin Historical Society recently secured a $113,912 Save America’s Treasures grant from the National Park Service to fund transport and freeze-drying at a Texas conservation facility. The 1,200-year-old canoe will eventually be displayed in the Wisconsin History Center, where it is expected to become a signature piece of the state’s early cultural history.

For Thomsen—whose career normally revolves around mapping Great Lakes shipwrecks—the canoe project carries a deeper emotional weight. Working directly with Wisconsin’s First Nations has reframed the excavation not as an isolated archaeological task, but as a collaborative uncovering of living heritage.

“Each one of these canoes gives us another clue to the story,” she said. “This work feels like it’s making a difference.”

Cover Image Credit: Wisconsin Historical Society via Facebook