Ancient textiles from the Judean Desert reveal that many Roman-era “purple” garments were not dyed with costly murex but with a clever blend of madder and woad, exposing a widespread fake-luxury industry 2,000 years ago.

The latest analyses of Roman-era textiles from the Judean Desert have uncovered a remarkably human story: social climbing, strategic imitation, and an ancient version of “luxury for less.” Research led by the Israel Antiquities Authority shows that many garments once thought to be dyed with the prestigious murex purple were, in fact, colored using a clever blend of cheaper plant-based dyes. The findings suggest a widespread market for convincing imitations—an early “Prada for the masses,” as one researcher put it—long before fast fashion and counterfeit brands reshaped the modern economy.

Prestige in a Thread: Why Color Mattered in the Roman World

Clothing in antiquity was never just functional. It was a declaration of identity, wealth, and ambition. Fabric quality mattered, decorative motifs mattered, and above all, color mattered. A single hue could mark the boundary between elites and everyone else.

No color carried more prestige than royal purple. Extracted from murex trunculus and related Mediterranean marine snails, the dye was infamous for its rarity, high cost, and slow multi-stage production process. Its brilliant spectrum—from deep violet to reddish burgundy—was associated with royalty, high-ranking officials, and religious elites.

“Dyeing with murex was an arduous process that took several days and required large quantities of snails,” says Dr. Naama Sukenik, curator of organic materials at the Israel Antiquities Authority and a leading expert on ancient dyes. “Today we can identify the unique molecular signature of murex, allowing us to determine with high confidence whether a textile was truly dyed with the most prestigious dye of the ancient world.”

📣 Our WhatsApp channel is now LIVE! Stay up-to-date with the latest news and updates, just click here to follow us on WhatsApp and never miss a thing!!

The Surprise: Most ‘Purple’ Garments Were Not Purple at All

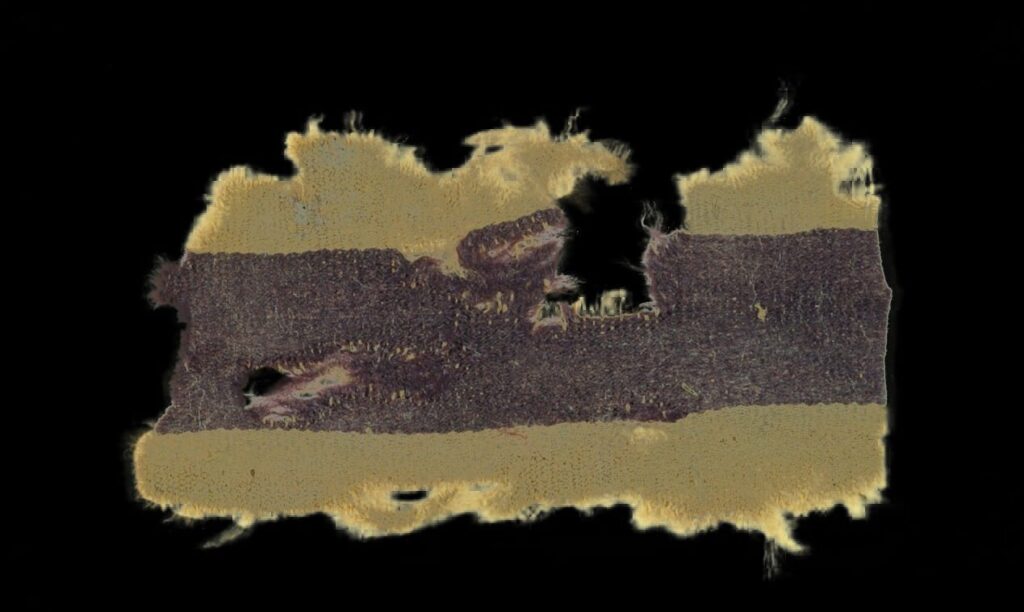

When dozens of 2,000-year-old textile fragments recovered from Judean Desert caves were tested, expectations were high. The fabrics were decorated in purple-like tones, and some had long been assumed to contain genuine murex dye.

What emerged instead was a clear pattern: the majority of these textiles were not dyed with murex at all.

Laboratory analysis showed that the deep purplish hues came from double dyeing with two plants commonly used in the ancient Near East:

Madder (Rubia) — producing a red dye from its roots

Woad (Isatis tinctoria) — producing a blue dye often described as the “Near Eastern indigo”

By carefully immersing the cloth in a madder dye bath and then a woad bath (or vice versa), ancient dyers produced a rich, blended hue visually similar to royal purple. The process required skill but no sea snails, no complex chemical extractions, and no days-long preparation.

“Double dyeing achieved a sophisticated imitation that could easily pass for authentic royal purple,” Dr. Sukenik explains. “Madder and woad were widely available, far cheaper, and far easier to work with than murex snails. Their use points to a deliberate strategy—creating prestige at a fraction of the cost.”

An Ancient Marketplace of Imitations

The discovery highlights a phenomenon that feels strikingly modern: fake luxury, tailored for people who wanted to display status without paying elite prices.

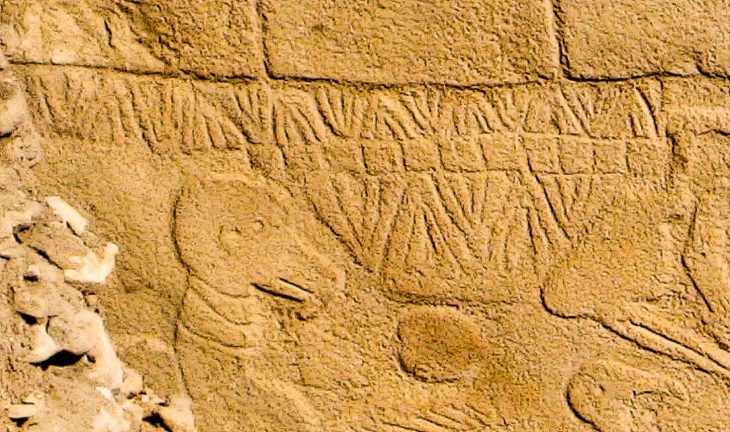

These plant-dyed textiles reveal that imitation was not a marginal practice—it was widespread, normalized, and accepted. And it was not a Roman invention. A Babylonian cuneiform tablet from the 7th century BCE already describes a dyeing “recipe” designed to mimic expensive purple.

“Human nature has not changed,” says Dr. Sukenik. “Even in antiquity, people wanted to appear as though they belonged to a higher social class. The use of imitation dyes made that possible.”

Archaeology Meets Social History

The textiles analyzed came from desert caves whose dry microclimate allowed fragile organic materials to survive. Each scrap of cloth helps reconstruct a social ecosystem where appearance, aspiration, and technology intersected.

The findings also reveal something about the ancient dyeing industry in the Land of Israel. Madder and woad were both cultivated regionally and frequently mentioned in Jewish sources. Their importance reflects not only economic pragmatism but also the technical proficiency of dyers who mastered color manipulation long before synthetic dyes were imagined.

A New Publication and Online Event

The research coincides with the launch of Thread and Color in the Textiles of the Land of Israel, a new book exploring the region’s textile heritage—from tekhelet (blue) to scarlet and genuine murex purple.

An online event hosted in partnership with Yad Yitzhak Ben-Zvi will take place this Thursday on Zoom, offering the public an opportunity to hear more about the dyes, traditions, and technologies behind these discoveries. Participation is free with prior registration.

Cover Image Credit: Clara Amit and Yuvaly Schwartz, courtesy of the Israel Antiquities Authority; Shahar Cohen, courtesy of Prof. Zohar Amar, Bar-Ilan University.