A 5,000-year-old rock inscription decoded by a University of Bonn Egyptologist offers rare insight into ancient Egyptian colonial domination in the Sinai Peninsula

A remarkable archaeological discovery in the southwestern Sinai Peninsula is reshaping our understanding of early Egyptian expansion and colonial power. A rock inscription dating back nearly 5,000 years has been identified as one of the oldest known visual representations of political domination in human history. Decoded by Egyptologist Professor Ludwig Morenz of the University of Bonn, the scene dramatically depicts the subjugation of the local Sinai population by early Egyptians, revealing how economic ambition, religious authority, and violence intersected at the dawn of civilization.

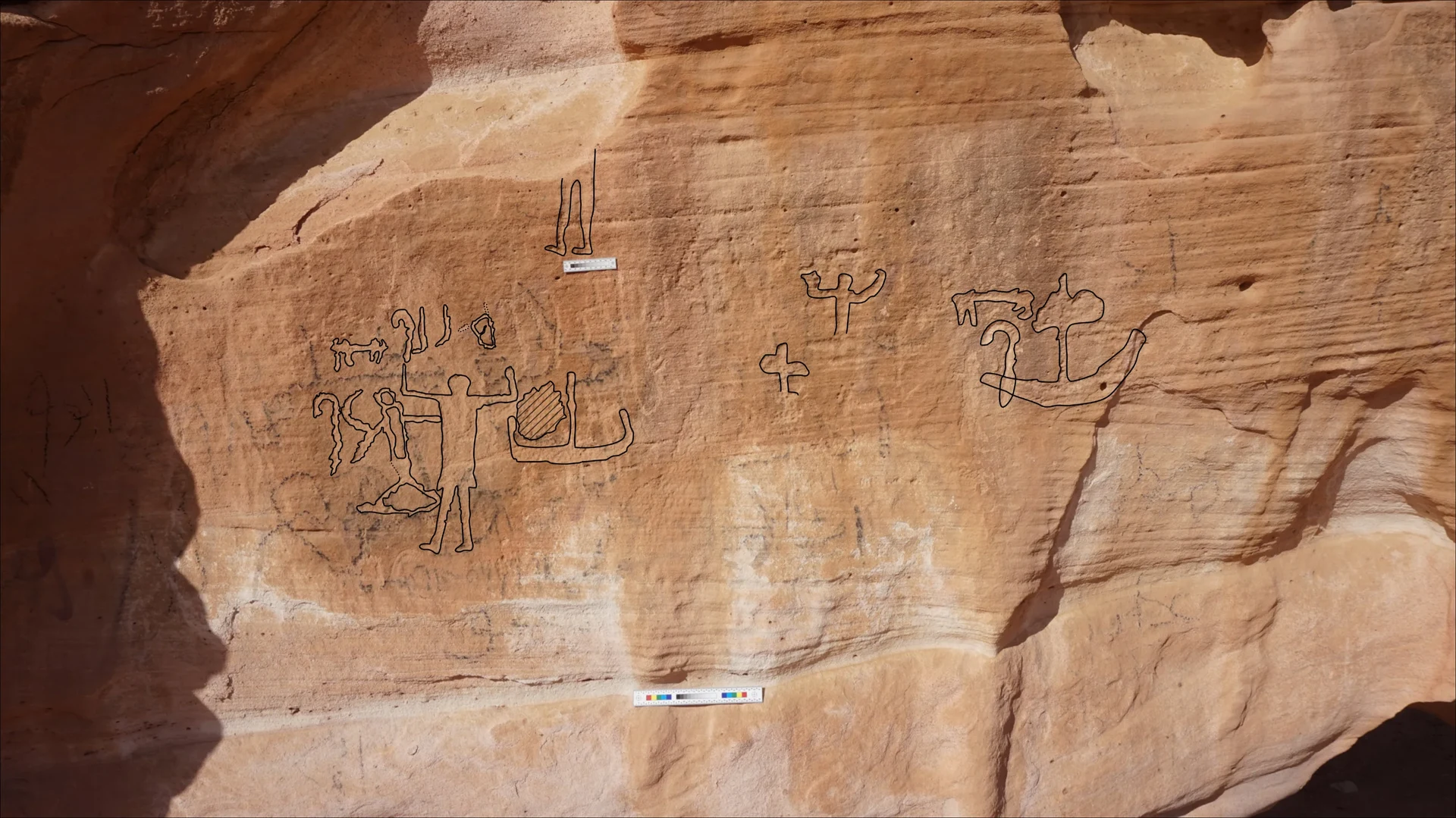

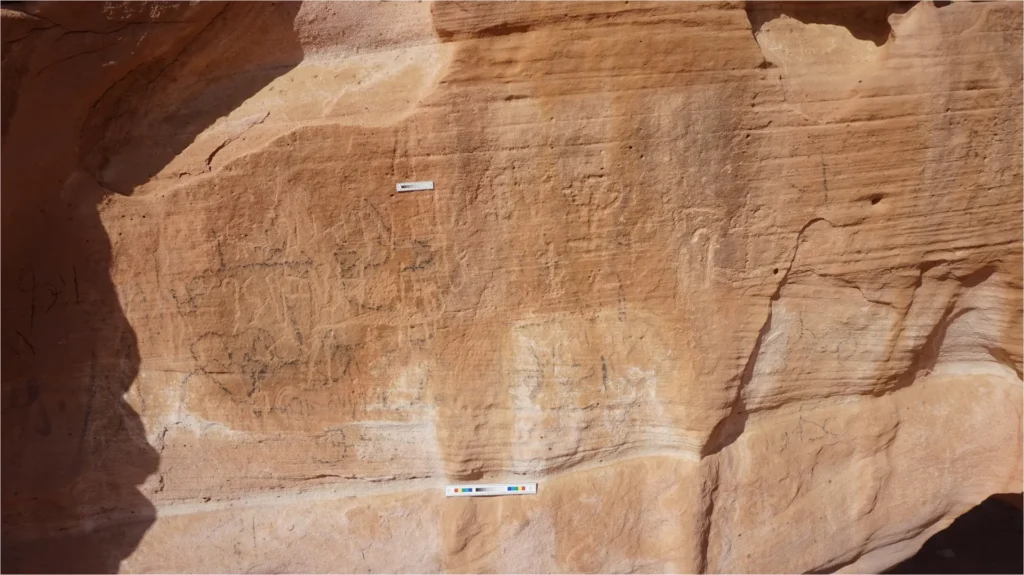

The inscription was discovered in Wadi Khamila, a dry valley in the southwest Sinai, by Mustafa Nour El-Din, an inspector from the Aswan branch of Egypt’s Ministry of Antiquities. Carved prominently onto a smooth and highly visible rock surface, the scene shows a towering male figure with raised arms—interpreted as either an Egyptian ruler or the god Min—standing triumphantly over a kneeling local inhabitant pierced by an arrow. The imagery leaves little doubt about its message: Egyptian dominance was absolute and intentionally displayed.

One of the Oldest Known Domination Scenes

According to Professor Morenz, the newly identified inscription is among the earliest known “smiting scenes”—iconic representations of victory and domination—accompanied by pictorial annotation. Such scenes later became a central motif in Egyptian royal ideology, but this discovery pushes their origins back to the late fourth millennium BCE.

“The southwestern Sinai is a region where we can clearly trace an economically motivated colonization by Egypt through images and inscriptions more than 5,000 years old,” Morenz explains. The scene in Wadi Khamila, he notes, was designed to instill fear and to visually proclaim Egyptian authority over a region that lacked writing systems or centralized political organization at the time.

📣 Our WhatsApp channel is now LIVE! Stay up-to-date with the latest news and updates, just click here to follow us on WhatsApp and never miss a thing!!

Economic Motives Behind Early Colonization

The Sinai Peninsula held immense strategic value for early Egypt. Rich in natural resources such as copper and turquoise, the region attracted Egyptian expeditions seeking raw materials critical for technological and symbolic purposes. The local inhabitants, who lived without a state structure or written language, were socio-culturally disadvantaged when confronted by these organized expeditions.

Until now, Wadi Khamila had only been known to researchers for much later Nabataean inscriptions, dating around 3,000 years younger than the newly discovered carving. The presence of such an early Egyptian inscription in this location was completely unexpected and significantly expands the known geographical reach of Egypt’s earliest colonial activities.

Dating the Inscription: A Scientific Challenge

Determining the precise age of rock inscriptions is notoriously difficult, but in this case, researchers relied on a combination of iconography, stylistic analysis, and epigraphy. The way the figures are carved, the posture of the dominant figure, and the symbolic elements all correspond with known Egyptian artistic conventions from the late fourth millennium BCE.

Cultural context further supports this dating. Historical evidence shows that Egyptian expeditions were already active in the southwest Sinai during this period, primarily for economic purposes. The inscription aligns closely with similar early Egyptian rock art found in Wadi Ameyra and Wadi Maghara, suggesting a broader system of territorial marking.

A Network of Colonial Symbols

Taken together, the inscriptions from Wadi Khamila, Wadi Ameyra, and Wadi Maghara point to what Morenz describes as a colonial network. These sites were carefully chosen: they are located along traditional travel routes, near resting places, and on rock surfaces that are highly visible within the landscape.

“Historically, places with prominent rock inscriptions often attracted repeated writing or even overwriting,” Morenz notes. The Wadi Khamila inscription itself bears traces of multiple later additions, including recent Arabic graffiti, demonstrating how such locations remain culturally significant across millennia.

Religion as Colonial Justification

One of the most striking aspects of the discovery is its explicit religious dimension. The dominant figure in the scene is closely associated with the Egyptian god Min, who served as the divine patron of early Egyptian expeditions during the fourth and early third millennia BCE.

“Although these inscriptions are often very short, religious justification played a crucial role in legitimizing colonization,” Morenz explains. By invoking Min, the inscription frames Egyptian dominance as divinely sanctioned. This religious authority was a defining feature ofwhat Morenz terms early Egyptian paleo-colonialism in the Sinai. In later periods, other deities such as Sopdu would assume similar roles.

A New Starting Point for Research

Compared to regions like Aswan, early inscriptions in Wadi Khamila are extremely rare, making this discovery all the more significant. Professor Morenz, who is also affiliated with the Bonn Center for Dependency & Slavery Studies, sees the find as a major turning point.

He plans further exploration of the area in search of additional early graffiti and inscriptions. Initial discussions with Egypt’s antiquities authorities are already underway to contextualize and protect the site.

“This discovery opens an entirely new chapter,” Morenz says. “It forces us to reconsider how early states used imagery, religion, and violence to assert control beyond their core territories.”

The 5,000-year-old rock inscription in Wadi Khamila stands not only as an archaeological treasure but also as a powerful reminder: the roots of colonial domination reach far deeper into human history than previously assumed.

Cover Image Credit: M. Nour El-Din/Umzeichnung: E. Kiesel