First tangible evidence of Greek theater in the Black Sea colony sheds light on the cultural life of the Bosporan Kingdom

Archaeologists excavating the ancient Greek city of Phanagoria on Russia’s Taman Peninsula have uncovered the first concrete evidence of a classical theater in the settlement. The discovery—a fragment of a terracotta actor’s mask depicting a satyr, a mischievous companion of Dionysus—dates to the 2nd century BCE and represents a milestone in understanding the cultural and religious life of one of the largest ancient Greek colonies in the Black Sea region.

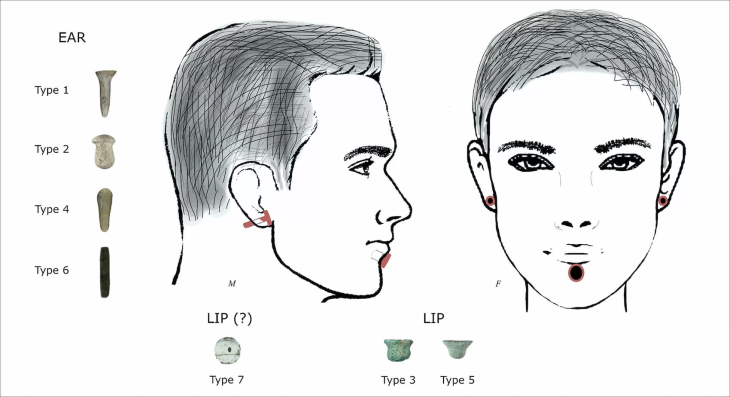

The find was made by the Phanagoria Archaeological Expedition, supported by the Oleg Deripaska “Volnoe Delo” Foundation. Measuring nearly 30 centimeters in length, the mask fragment preserves the left side of the satyr’s face, complete with exaggerated cheekbones, a large ear, and thick beard. The painted details are still visible: a blue-outlined eye and reddish beard and mustache, characteristic features of masks used in New Comedy performances.

According to researchers, the size, stylistic details, and perforations for straps confirm that this was a genuine theatrical prop rather than a miniature votive mask.

Theatrical Culture in Ancient Phanagoria

Greek actors traditionally used masks to embody different roles and to project emotions to audiences in large open-air theaters. Distinctive colors and facial exaggerations helped identify characters: a fiery red beard, for instance, signaled hot temper and unruly nature. The satyr mask fragment aligns with the well-known iconography of Dionysus’s goat-footed attendants, depicted with disheveled hair and horseshoe-shaped mustaches.

📣 Our WhatsApp channel is now LIVE! Stay up-to-date with the latest news and updates, just click here to follow us on WhatsApp and never miss a thing!!

The discovery suggests that Phanagoria, like other poleis of the Bosporan Kingdom, maintained a vibrant cultural life that included theatrical performances and Dionysian festivals. Theater was not merely entertainment—it was deeply tied to religious rituals honoring Dionysus, god of wine and ecstatic transformation. During Mithridates VI Eupator’s reign (120–63 BCE), when the king embraced Dionysus as his divine patron, the cult flourished in Phanagoria. Theatrical masks, processions, and imagery of Dionysus and his companions appeared widely on coins, ceramics, and votive objects of the era.

Archaeological Context and Previous Finds

The satyr mask fragment was unearthed in the central part of the ancient city, near what researchers believe could have been the location of the theater. Smaller ritual masks, no more than 10 centimeters in height, had previously been recovered from shrines in Phanagoria—two depicting satyrs and one a comic actor. These miniature masks were affixed to wooden posts and offered to the gods with prayers for healing and other favors.

However, the newly discovered large-scale mask marks the first direct archaeological evidence of a functioning theater in Phanagoria. Ancient sources had hinted at the presence of theaters in the Northern Black Sea. The Greek writer Polyaenus, in the 4th century BCE, described how the general Memnon sent a singer named Aristonikos to the Bosporus. The local population, rushing to theaters to hear him, inadvertently revealed their numbers and military strength.

Dr. Vladimir Kuznetsov, head of the Phanagoria Expedition, emphasized:

“There is no doubt that Phanagoria had a theater. We suggest it was located on a hill with a commanding view of the sea and the city of Panticapaeum—modern Kerch—the capital of the Bosporan Kingdom.”

Phanagoria: The Forgotten Metropolis of the Black Sea

Founded around 543 BCE by Greek colonists from Teos, Phanagoria rapidly became one of the most important settlements on the Taman Peninsula, strategically positioned between the Black Sea and the Sea of Azov. It was a thriving hub of trade, politics, and culture, at times rivaling Panticapaeum on the opposite side of the strait.

During the Hellenistic period, Phanagoria became a key city of the Bosporan Kingdom, maintaining connections with both Greek and local Scythian populations. In 63 BCE, it became a stronghold of Mithridates VI Eupator, who made it his capital during his final resistance against Rome.

Archaeological excavations have been ongoing since the 19th century, but the modern Phanagoria Expedition, led by the Russian Academy of Sciences with support from the Volnoe Delo Foundation, has dramatically expanded knowledge of the site. Major discoveries include the remains of a royal palace linked to Mithridates, early Christian basilicas, extensive necropoleis, and inscriptions shedding light on governance and daily life. The theater mask adds a new dimension to the city’s cultural profile.

Broader Implications

The find reinforces the view that Greek cultural traditions took deep root in the Black Sea colonies, blending with local practices and influencing subsequent civilizations. Theatrical life in Phanagoria demonstrates that even at the empire’s periphery, Hellenistic art, literature, and religion were actively practiced and adapted.

Moreover, the mask’s Dionysian symbolism underscores the city’s close identification with the cult of the god of wine, fertility, and transformation—a cult that not only celebrated ecstasy but also played a political role in legitimizing rulers like Mithridates VI.

For archaeologists, the satyr mask is not just an artifact—it is a piece of living theater history, bridging the gap between written sources and material culture.

Echoes of a Forgotten Stage

The satyr mask from Phanagoria is more than a fragment of terracotta — it is the echo of voices, music, and ritual that once animated a theater on the shores of the Black Sea. For the first time, archaeology has turned literary hints into tangible proof, showing that the people of Phanagoria laughed, wept, and worshipped through the same performances that shaped the wider Greek world.

Rather than a silent ruin, the city now emerges as a stage where religion, politics, and art converged. As future excavations continue to peel back its layers, each discovery brings us closer to hearing the forgotten chorus of a cosmopolitan metropolis that thrived far from Athens, yet beat in rhythm with it.

Cover Image Credit: Artistic reconstruction of the satyr theater mask discovered in Phanagoria. Oleg Deripaska’s Volnoe Delo Foundation