Archaeologists in Switzerland have uncovered compelling evidence that reshapes our understanding of everyday life in Roman-era Europe: camels — yes, camels — once lived and worked in Basel nearly 1,700 years ago. Recent findings from the Archaeological Research Office of Basel-Stadt reveal that bones discovered beneath the modern city belonged to a rare hybrid camel used by the Romans for transport, logistics, and military activities. This remarkable discovery not only broadens our knowledge of Roman trade and mobility, but also highlights Basel’s surprising role within the vast, interconnected network of the Roman Empire.

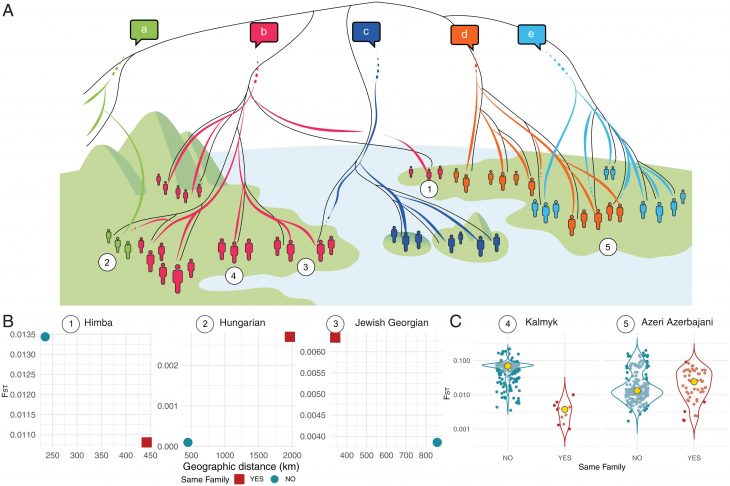

The findings are presented in the 2024 Annual Report of the Archaeological Research Office of Basel-Stadt, in a detailed study authored by archaeologists Barbara Stopp, Sabine Deschler-Erb, Claudia Gerling, and Andrea Hagendorn. In their illustrated report, the researchers analyze the so-called “desert ships on the Rhine,” combining zooarchaeology, isotope analysis, and historical context to confirm that the remains belong to a rare hybrid camel transported to Basel during the Roman period.

A surprising discovery beneath the streets of Basel

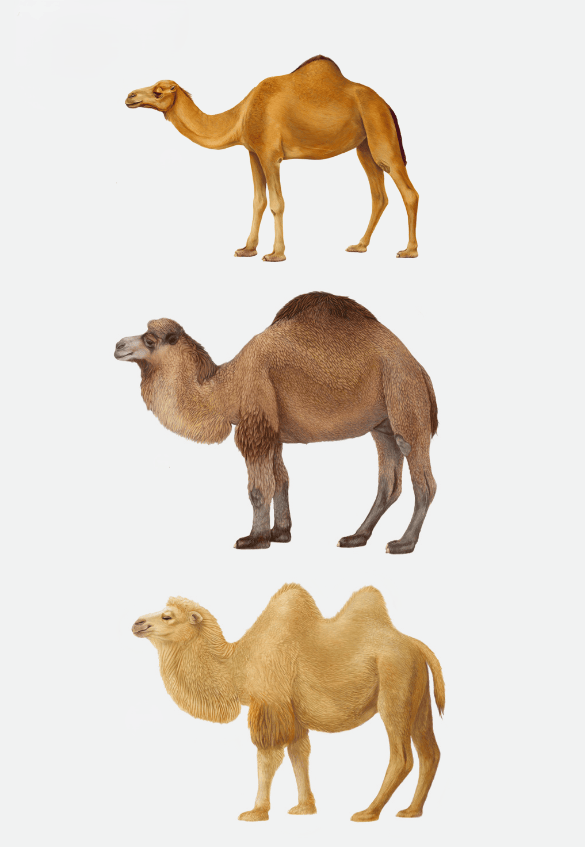

The story begins with the study of a fragmented animal mandible unearthed during excavations near the Spiegelhof area in central Basel. At first glance, the bone seemed unremarkable — one of many animal remains commonly found at Roman archaeological sites. But detailed scientific analysis transformed this ordinary-looking jawbone into an extraordinary historical clue. The teeth and bone structure revealed that the animal was a hybrid camel, created by cross-breeding a single-humped dromedary with a two-humped Bactrian camel.

Such hybrids were highly valued in antiquity. They combined the strength and endurance of Bactrian camels with the speed and adaptability of dromedaries, making them ideal for transporting heavy loads across diverse terrain. Even more revealing was the isotope analysis of the tooth enamel, which showed that the animal did not originate in Europe and had changed regions at least twice during its lifetime. This indicates a long journey — most likely from North Africa or the Arabian Peninsula — before eventually reaching the northern frontier of the Roman Empire along the Rhine.

Additional bone fragments discovered during excavations in both 1939 and 2018 suggest that more than one camel may once have been present in Basel. Together, these remains represent the westernmost archaeological evidence of hybrid camels in Europe discovered so far.

📣 Our WhatsApp channel is now LIVE! Stay up-to-date with the latest news and updates, just click here to follow us on WhatsApp and never miss a thing!!

Why were camels brought to Roman Switzerland?

Although camels are typically associated with desert landscapes rather than Central European river valleys, they played a documented role in the Roman world. Roman military units especially in eastern and African provinces relied on camels as efficient pack animals capable of transporting supplies over long distances and challenging terrain. Historical sources even mention specialized camel-rider units known as Dromedarii, who supported frontier defense, logistics, courier services, and communication across remote regions.

Hybrid camels were particularly practical for deployment in northern Europe. Unlike pure dromedaries, these hybrids could better withstand cold, wet climates and muddy ground, conditions common along the Rhine frontier. Their resilience made them well-suited for travel between forts, supply depots, and major routes within the Roman road system.

The camel bones in Basel were discovered along the course of a Roman road that connected the fortified settlement on the Münsterhügel with broader international transport routes. This same road passed through Augusta Raurica, another significant Roman settlement where camel remains have also been found. Archaeologists believe that the same Roman legion responsible for construction and reinforcement projects in both locations — the Legio Prima Martia — may also have facilitated the arrival of these animals in the region.

Basel’s strategic role on the Roman frontier

The camel remains have been dated to the fourth century CE, a period marked by military consolidation along the Rhine. During this era, the Roman commander and later emperor Valentinian I stationed his army in Basel, strengthening fortifications and organizing campaigns against Germanic groups across the river. It was also at this time that a small fortress in Kleinbasel — described in ancient texts as “Munimentum prope Basiliam” — provided one of the earliest recorded mentions of the name Basel.

In this strategic context, the presence of camels becomes easier to understand. Rather than exotic curiosities, they were almost certainly working animals integrated into military logistics, helping transport equipment, food supplies, and construction materials essential to frontier defense.

Evidence of global connectivity in antiquity

This discovery offers more than a fascinating local anecdote — it provides powerful proof of the long-distance connections that shaped the Roman Empire. The camel’s journey from desert regions to the Rhine valley reflects sophisticated trade networks, military supply systems, and cross-regional exchanges linking distant provinces.

Roman forces rarely bred camels themselves. Instead, they typically purchased animals from professional breeders and traders in North Africa and Southwest Asia. That means the Basel camel was oncepart of a commercial and logistical system stretching across continents — a vivid reminder that mobility and globalization are not purely modern phenomena.

The choice of hybrid camels also demonstrates strategic adaptation. Rather than forcing animals into unsuitable environments, the Romans deliberately selected species that were better suited to European weather and terrain, reflecting advanced knowledge of animal husbandry and resource planning.

Why this discovery matters today

From an archaeological viewpoint, the Basel camel findings enrich our understanding of mobility, infrastructure, and environmental adaptation in late Roman Europe. They challenge assumptions that camels were limited to desert regions and reveal instead how the empire repurposed resources from across its territories to meet local needs.

For the city of Basel, the discovery reinforces its identity as a historic crossroads of cultures, trade, and military activity stretching back nearly two millennia. It also invites the public to re-imagine the past — to picture Roman soldiers and laborers leading sturdy hybrid camels along muddy roads that still influence the city’s urban layout today.

Looking ahead: uncovering more of Basel’s hidden past

Ongoing archaeological research in Basel continues to shed light on settlement history from prehistoric times through the Middle Ages. As scientists refine dating methods and analyze additional material, new insights may emerge about how many camels once lived in the region, how they were used, and how they fit into broader networks across Roman Switzerland.

What we already know, however, is extraordinary: during the Roman era, camels really did live in Basel — and their story is helping rewrite the history of Europe’s northern frontier.

Archaeological Research Office of Basel-Stadt

Cover Image credit: The jawbone of a hybrid camel that came to rest beneath today’s Spiegelhof around 1,700 years ago. The lighter bone fragments were discovered in 1939, while the darker ones were only found in 2018. Archaeology Basel-Stadt; P. Saurbeck.