Deep inside a limestone cave on the Indonesian island of Sulawesi, faint red handprints sprayed onto rock walls nearly 70,000 years ago are forcing scientists to rethink when, where, and how modern humans first expressed symbolic thought.

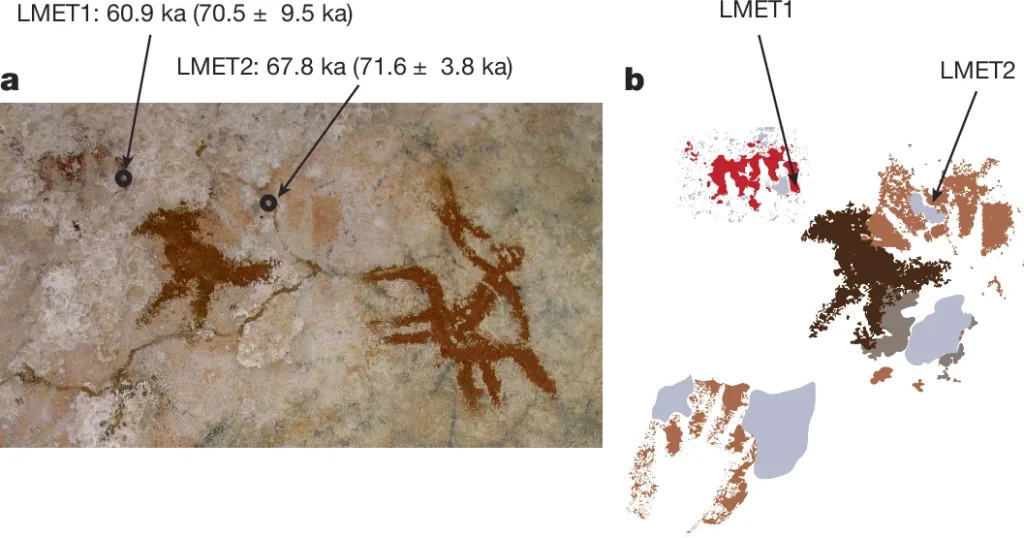

An international team of archaeologists has identified the oldest known hand stencil rock art in the world, dated to at least 67,800 years ago, at the cave site of Liang Metanduno in Southeast Sulawesi. The discovery, published in Nature, predates Europe’s earliest known cave art and places Indonesia at the very centre of the story of human creativity.

These ancient hand stencils—negative impressions created by spraying pigment around an outstretched hand—are more than simple marks on stone. According to researchers, they represent some of the earliest evidence that humans used art to communicate identity, presence, and meaning.

Older Than Europe, Older Than Expected

Using advanced laser-ablation uranium-series dating, scientists analysed calcium carbonate deposits that formed naturally over the paintings. The results showed that one hand stencil was created at least 67.8 thousand years ago, while another nearby stencil dates to more than 60,000 years ago. These ages make the Sulawesi hand stencils older than famous European cave art traditionally associated with the dawn of human creativity.

Until recently, many scholars believed symbolic art emerged first in Europe around 40,000 years ago. The Sulawesi discoveries challenge that long-held assumption.

📣 Our WhatsApp channel is now LIVE! Stay up-to-date with the latest news and updates, just click here to follow us on WhatsApp and never miss a thing!!

“This is the earliest securely dated evidence for hand stencil art anywhere in the world,” said Professor Adam Brumm of Griffith University, one of the study’s senior authors. “It shows that humans in Island Southeast Asia were producing complex symbolic art tens of thousands of years earlier than previously thought.”

A Global First for Hand Stencil Rock Art

Hand stencils are among the most widely distributed forms of prehistoric art, appearing on cave walls across Europe, Asia, Australia, and the Americas. However, until recently, most of the earliest dated examples were thought to come from Europe and to be around 40,000 years old.

The Sulawesi hand stencils fundamentally change that picture. At Liang Metanduno, one stencil was dated to a minimum age of 67.8 thousand years, while another nearby stencil indicates repeated artistic activity at the site over tens of thousands of years.

These findings suggest that symbolic behaviour—using images to mark presence, identity, or meaning—was already well established among early humans in Island Southeast Asia during the Late Pleistocene.

Distinctive Hand Shapes and Cultural Traditions

One of the most unusual aspects of the Sulawesi hand stencils is their distinctive finger morphology. Several examples show narrowed or modified fingers, a feature rarely documented elsewhere in the prehistoric art record.

The repeated appearance of this trait suggests it was intentional rather than accidental, pointing to shared cultural conventions among the artists. Researchers note that this stylistic tradition appears to have persisted for a long period, indicating cultural continuity rather than isolated acts of decoration.

These artistic traditions align with archaeological evidence from nearby sites showing long-term human presence and repeated use of caves as meaningful places within the landscape.

Sulawesi’s Deep Human History

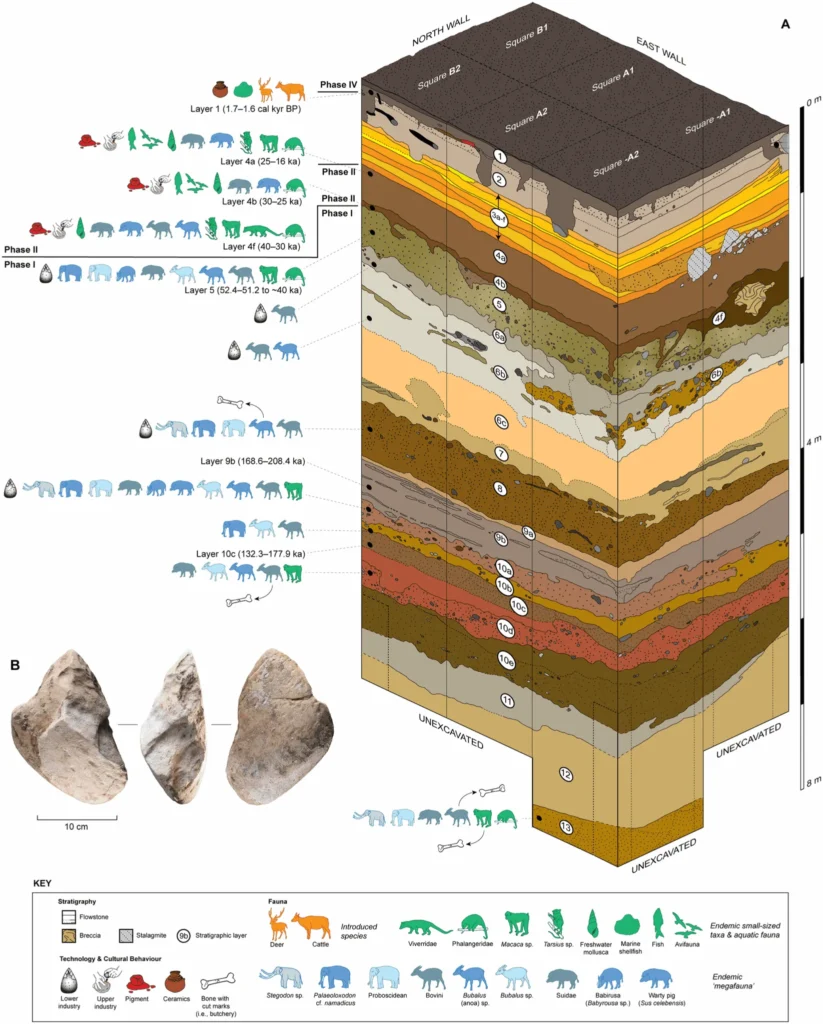

The hand stencil discoveries gain additional significance when viewed alongside archaeological excavations at Leang Bulu Bettue, a cave site in South Sulawesi that preserves one of the deepest and most continuous records of human activity in Wallacea.

Excavations at Leang Bulu Bettue have revealed archaeological deposits extending more than eight metres below the current ground surface, with evidence of human occupation dating to at least 132,000–208,000 years ago. These early layers contain stone tools, animal remains, and signs of systematic butchery that predate the arrival of modern humans on the island.

“The depth and continuity of the cultural sequence at Leang Bulu Bettue now positions this cave as a flagship site for investigating whether these two human lineages overlapped in time,” said Basran Burhan, a PhD candidate from South Sulawesi who led the excavations under the supervision of Professor Adam Brumm from Griffith University.

Previous research has shown that archaic hominins occupied Sulawesi from at least 1.04 million years ago, while Homo sapiens are thought to have reached the island sometime before the initial peopling of Australia around 65,000 years ago.

A Major Cultural Transition

Archaeological evidence from Leang Bulu Bettue indicates a dramatic cultural shift around 40,000 years ago. Earlier occupation layers dominated by cobble-based stone tools and animal remains—particularly dwarf bovids known as anoas and now-extinct Asian straight-tusked elephants—were replaced by a new technological and cultural phase.

“This later phase featured a distinct technological toolkit, and the earliest known evidence for artistic expression and symbolic behaviour on the island – hallmarks associated with modern humans,” Mr Burhan said.

According to the research team, this behavioural break may reflect a major demographic transition linked to the arrival of Homo sapiens and the disappearance of earlier hominin populations on Sulawesi.

Implications for Human Migration

The great antiquity of the Sulawesi hand stencils also has implications for understanding early human migration. The sites lie along the northern route through Wallacea, one of the pathways proposed for modern humans travelling from mainland Asia to Australia.

The presence of sophisticated symbolic art in this region before 65,000 years ago supports the idea that early humans moving through Island Southeast Asia already possessed advanced cognitive and cultural capabilities.

“That is why doing archaeological research in Sulawesi is so exciting,” Professor Brumm said.

“But there were hominins in Sulawesi for a million years before we showed up, so if you dig deep enough, you might go back in time to the point where two human species came face-to-face.”

An Incomplete Story

Researchers emphasize that both the rock art sites and the deep archaeological deposits of Sulawesi remain only partially explored. At Leang Bulu Bettue, excavations have not yet reached the bottom of the cultural sequence, leaving open the possibility of even older discoveries.

“There may be several more metres of archaeological layers below the deepest level we have excavated,” Mr Burhan said.

Together, the world’s oldest hand stencils and the deep archaeological record of Sulawesi underscore the island’s critical role in rewriting the global story of human origins, symbolic behaviour, and early migration.

Oktaviana, A.A., Joannes-Boyau, R., Hakim, B. et al. Rock art from at least 67,800 years ago in Sulawesi. Nature (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-025-09968-y

Cover Image Credit: Griffith University