For decades, archaeologists working at Tanis have grappled with an unsettling mystery: why was an unmarked granite sarcophagus lying deep inside the royal tomb of Osorkon II, yet containing no inscription to indicate its owner? Now, a major new discovery suggests that this secrecy was no accident — and that Pharaoh Shoshenq III may have been deliberately hidden away in a predecessor’s tomb, the victim of a political burial decision that reshaped the final chapter of Egypt’s 22nd Dynasty.

An Egyptian–French archaeological mission has uncovered 225 ushabti figurines bearing the name of Shoshenq III inside the northern chamber of Osorkon II’s burial complex. These figurines, preserved in compacted layers of silt, lay only a few steps from the long-mysterious, uninscribed sarcophagus discovered in 1939.

The evidence, according to the Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities, unmistakably points to one conclusion: Shoshenq III was buried here — but not by original design.

A Burial Hidden in Plain Sight

Until now, scholars assumed Shoshenq III rested in his own tomb somewhere else in the necropolis. But the placement of his funerary figurines inside another king’s chamber tells a different story — one marked by political turbulence and perhaps deliberate concealment.

Dr. Mohamed Ismail Khaled, Secretary-General of the Supreme Council of Antiquities, described the discovery as “a turning point in our understanding of Tanis’ royal necropolis.”

📣 Our WhatsApp channel is now LIVE! Stay up-to-date with the latest news and updates, just click here to follow us on WhatsApp and never miss a thing!!

He emphasized that the configuration of the ushabtis demonstrates that Shoshenq III was interred inside Osorkon II’s tomb, overturning decades of assumptions and raising profound questions about why this burial was moved or hidden.

A Dynasty in Crisis

To understand why a powerful pharaoh might lose his own tomb, the complex political environment of the 22nd Dynasty must be considered.

Shoshenq III (c. 825–773 BCE) ruled Egypt during one of the most politically fractured phases of the Third Intermediate Period. His reign unfolded against the backdrop of a prolonged dynastic conflict, as rival branches of the royal family struggled for dominance and legitimacy. Egypt was effectively split between competing authorities in the north and the south, creating a landscape in which several kings could reign at the same time. This fragmentation steadily weakened the centralized power of the monarchy, while local military elites and regional governors accumulated increasing influence.

Despite this turmoil, Shoshenq III maintained control over the Delta and sponsored monumental architecture at Tanis, including major temple gateways. Yet his long reign did not prevent the dynasty from fragmenting, nor did it guarantee the security of his burial.

New evidence suggests that after his death, his original tomb may have been appropriated by successors or political rivals. Some objects linked to his burial carry the name of Shoshenq IV, a later king associated with the emerging 23rd Dynasty — further supporting the idea of tomb usurpation.

This scenario aligns with the growing hypothesis that Shoshenq III was relocated into Osorkon II’s chamber, both because it was secure and because political forces made retaining his own tomb impossible.

Material Proof Beneath the Delta

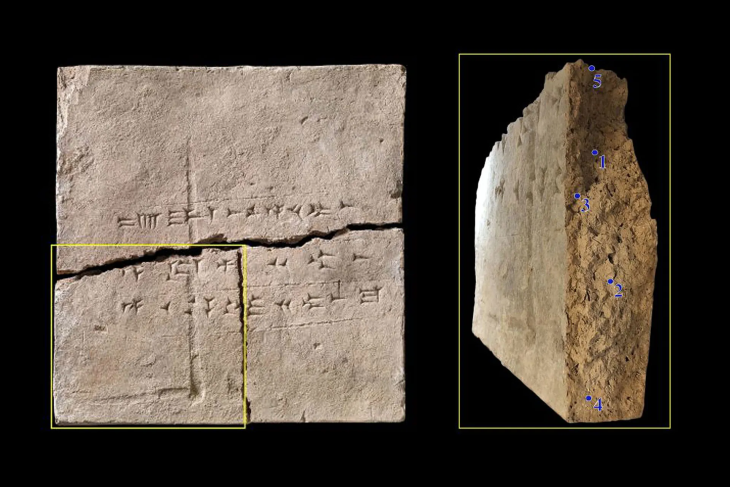

The 225 ushabtis discovered in the northern chamber are crafted from fine faience and clearly inscribed with Shoshenq III’s name and titles. Their proximity to the uninscribed sarcophagus provides decisive material evidence that this coffin — long considered an anomaly — is in fact his.

Dr. Frédéric Payraudeau, director of the French mission, highlighted that the figurines, wall markings, and spatial arrangement collectively confirm that Shoshenq III was buried here.

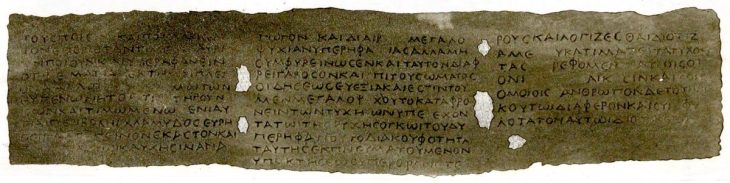

The team also uncovered new, previously undocumented inscriptions, which may illuminate whether the reburial was an emergency response to political instability or part of a calculated strategy to protect the king’s remains.

Tanis: A Site That Changes History Again and Again

Tanis, often overshadowed by the Valley of the Kings, is one of the most historically transformative archaeological sites in Egypt. Its royal burials — many found intact — offer unparalleled insights into Third Intermediate Period funerary practices.

Current conservation efforts at the necropolis include structural cleaning, desalination processes, and the installation of modern protective coverings to stabilize the tombs and support ongoing research.

Each season reveals new evidence that forces scholars to reassess the political and cultural realities of Egypt’s northern capitals.

A Royal Cover-Up or a Rescue Burial?

The identification of Shoshenq III’s resting place revives long-standing questions about the nature of royal authority during this period. Was the pharaoh’s tomb seized by a successor? Was he reburied for protection during civil war? Or was his memory intentionally obscured?

Whatever the motivation, the discovery reveals a dramatic act of political decision-making at the heart of the 22nd Dynasty — an act that placed one king’s remains in the sacred chamber of another.

As archaeologists continue to study the newly revealed inscriptions and architectural context, one thing is clear: Tanis continues to expose stories of royal rivalry, shifting power, and hidden history — often buried just beneath the surface.

Egyptian Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities

Cover Image Credit: Egyptian Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities via Facebook