Archaeologists have discovered animal bones and habitation evidence underneath the northern part of Stavanger cathedral that they believe date from the Viking Age. This might finally resolve the question of what existed on the site before the church was erected.

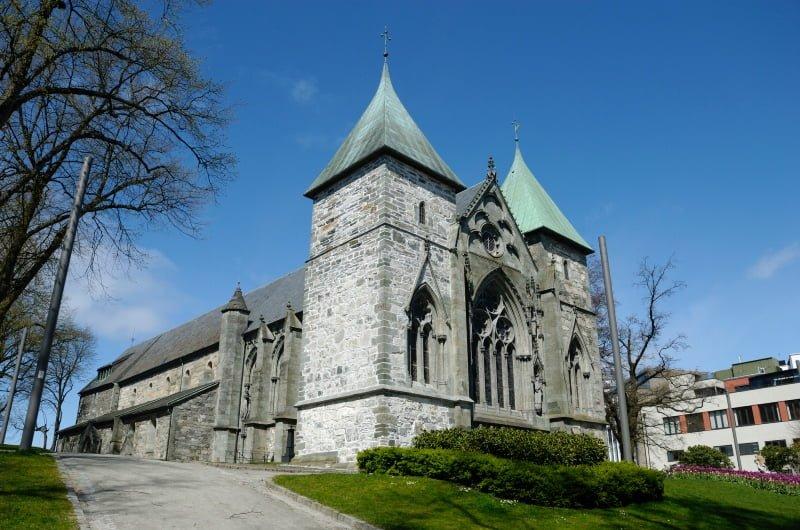

Stavanger Cathedral is Norway’s oldest cathedral. The gray, stone church was built in a long church style around the year 1125 using designs by an unknown architect. It has been in continuous use since it was built.

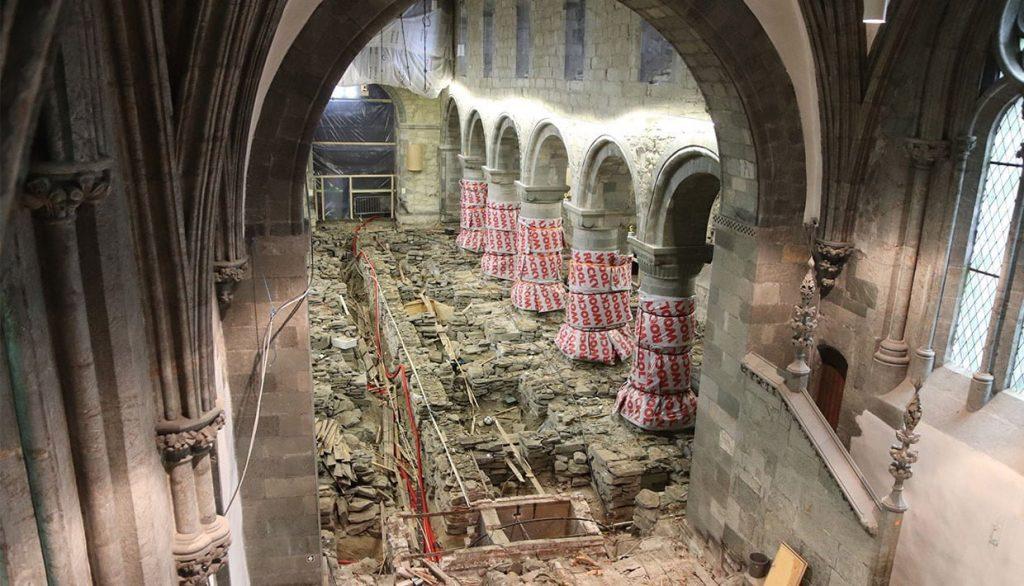

Archaeologists are investigating the crawl space in Stavanger cathedral. The work is being done in conjunction with the cathedral’s restoration in preparation for the city’s centennial festivities in 2025.

The project was carried out by archaeologists from the Norwegian Institute for Cultural Heritage Research (NIKU) and the Archaeological Museum of the University of Stavanger (UiS).

Pig bones and settlement traces

“In the northern chambers of the church we have found thin, dark soil layers with a completely different character than in the rest of the areas we have investigated so far,” said excavation leader Kristine Ødeby.

📣 Our WhatsApp channel is now LIVE! Stay up-to-date with the latest news and updates, just click here to follow us on WhatsApp and never miss a thing!!

Animal bones were found within the soil layers, most notably skeletal remains of a pig. Archaeologists believe they date the find to the first half of the 11th century, or older. This is before the cathedral was built.

“What we have found is the bones of a pig, which were clearly placed with meat and skin intact. They have been lying there until now,” said UIS’s Sean Denham.

Helps to prove a Viking settlement

The construction of the church started in the second half of the 11th century. Archaeologists believe it would have been very unlikely that the pig bone was placed in the church after this.

Denham explained that there is no tradition of placing relics into Norwegian medieval churches: “Everything indicates that the bones must have ended up exactly where we found them before the present church was built.”

NIKU’s Halldis Hobæk said the theory of a Viking Age settlement at the site corresponds well previous findings. During the 1960s, UiS conducted archaeological research under the church.

“In 1968, they found a layer of burnt wood under the altar area. This was dated to Viking times, and is interpreted as a remnant of a burnt down building,” she said.

The finding confirms that the cathedral was not built in an uninhabited and desolate place, but rather a place where there was already human activity.

Archaeologists have also found far more graves than expected. There’s also evidence that much archaeological material was removed in the 19th century.

Kristine Ødeby said that the preliminary results are very exciting: “We knew that we would find graves under the floor in the cathedral, but the number and extent of them is currently greater than we imagined.”

There were graves in all chambers examined so far. The graves have not yet been formally dated but the team already has a good idea of when they are from.

“The tombs we assume are both from the Middle Ages and from the 16th to 18th centuries. Some may be older than this,” said Ødeby.

The grave finds go well beyond skeletons. In addition to bones, the graves include fragments of wooden coffins, iron nails assumed to be from coffins and some objects including remnants of jewellery and bronze needles.

“A particularly interesting find is several blue, white and black pearls. We wonder if these came from a rosary, and if so it is reasonably certain that it is from the period when the church was still Catholic, ie before the Reformation in 1537,” said Ødeby.

In the six chambers examined so far in the study, the so-called “cultural layers” are not particularly deep. Cultural layers refer to areas in which remains of human activity are found.

The cultural layers discovered so far are no more than 15cm deep, which leads archaeologists to believe a lot of material was dug away in the Middle Ages.

Source: Life in Norway