A lost Aeschylean version of the Trojan War emerges from the Rutland mosaic, revealing Roman Britain’s surprising cultural ties to the wider Mediterranean world.

For five years, a team of historians and archaeologists at the University of Leicester had been circling around a mystery. Beneath the quiet fields of Rutland, far from the sun-soaked ruins of Greece or Türkiye, lay one of the most startling pieces of Roman art ever uncovered in Britain—a sprawling, brilliantly composed mosaic unlike any other found on the island. But its true significance only emerged recently, when researchers realized it was telling a story the modern world had all but lost.

The Ketton mosaic, a masterwork crafted around 1,800 years ago, does not simply retell the familiar episodes of Homer’s Iliad. It reaches deeper into antiquity, drawing instead on a forgotten tragedy by Aeschylus, the great Athenian dramatist whose works once electrified classical audiences. His play Phrygians, long vanished except for a handful of references, resurfaces here as a sweeping visual narrative—preserved not in a manuscript, but in tesserae set meticulously into a villa floor at the northern edge of the Roman Empire.

The revelation reframes the mosaic as more than a rare archaeological treasure. It becomes a bridge between worlds, proof that Roman Britain was not a cultural frontier but an active participant in the classical imagination that tied the Mediterranean together.

The story begins in 2020, during the isolation of the COVID-19 lockdown, when farmer Jim Irvine noticed fragments of patterned stone emerging from the earth of his family’s land. His curiosity led him to alert specialists, drawing the attention of the University of Leicester Archaeological Services and Historic England. What they uncovered was astonishing: a villa complex of considerable size and luxury, its central room adorned with a mosaic nearly 11 meters long—a canvas of war, grief, and mythological grandeur.

📣 Our WhatsApp channel is now LIVE! Stay up-to-date with the latest news and updates, just click here to follow us on WhatsApp and never miss a thing!!

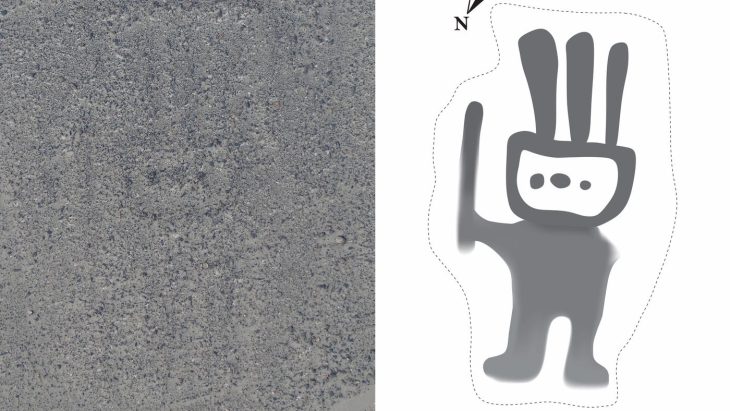

The mosaic unfolds in three scenes, each devoted to the rivalry between Achilles and Hector. The duel itself is rendered with dynamic energy, each figure poised in the tension before impact. The next scene portrays the aftermath—Achilles driving his chariot as Hector’s lifeless body trails behind, a moment of brutality that continues to shock after two millennia. But it is the final panel that changed everything. There, Hector’s body is weighed against gold as King Priam ransoms his son.

That image does not appear in Homer. It never has. Instead, it belongs to the lost Aeschylean version of the myth, an alternate telling known only from ancient commentary and now from this mosaic. The detail is more than an artistic choice; it is a scholarly earthquake. It suggests that the villa’s owner, and the artisans commissioned to decorate his floor, were drawing from a version of the Trojan legend that was already rare in the Roman world, hinting at a household deeply engaged with classical literature beyond the standard canon.

Yet what makes the mosaic even more extraordinary is the lineage of its artistic vocabulary. Lead researcher Dr. Jane Masséglia and her colleagues identified patterns and motifs lifted from designs circulating across the Mediterranean for centuries before the mosaic was even conceived. One upper panel mirrors a layout found on a Greek vase from the very era of Aeschylus himself. Elsewhere, the visual language echoes Roman silverware from Gaul, coin iconography from Asia Minor, and decorative traditions passed from workshop to workshop long before they reached the shores of Britain.

Such connections undermine the long-held assumption that Roman Britain was a cultural backwater. Instead, they reveal a province plugged into the currents of Mediterranean art, trade, and intellectual life. The craftsmen who laid the mosaic were not isolated artisans improvising at the edge of empire. They were heirs to a network of pattern books, motifs, and techniques that moved from continent to continent as fluidly as any written text.

The villa’s owners, too, must have been people of education, wealth, and aspiration—individuals who saw value in aligning their domestic space with stories that spoke to the deepest roots of classical culture. In the harsh winters of Britannia, far from the Aegean homeland of Achilles and Hector, they curated an artistic world that announced their sophistication to every guest who crossed their threshold.

For Irvine, who discovered the masterpiece by accident, the implications are thrilling. The mosaic, he says, paints a picture of a Roman Britain far more cosmopolitan than the one schoolbooks often describe—a place where global narratives lived vividly in the minds of provincial elites.

Scholars unaffiliated with the project agree. The mosaic, says Professor Hella Eckhardt, demonstrates how myths were preserved not only in literature but in the visual traditions artists transmitted across centuries and continents. It is a reminder that ancient stories traveled through hands as much as through words.

Today, the Ketton mosaic and its surrounding villa are protected as a Scheduled Monument, their importance securely recognized. But the deeper significance of the discovery continues to unfold. The mosaic not only extends the reach of Aeschylus’s lost drama; it alters our understanding of how Roman Britain saw itself—connected, informed, and culturally ambitious.

On a quiet farm in Rutland, the stones have begun to speak again. And what they’re telling us is that the edge of empire was never as distant from the classical world as we imagined.

Masséglia, J., Browning, J., Taylor, J., & Thomas, J. (2025). Troy Story: The Ketton Mosaic, Aeschylus, and Greek Mythography in Late Roman Britain. Britannia, 1–42. doi:10.1017/S0068113X25100342

Cover Image Credit: The duel between Achilles and Hector (Panel 1, bottom). ULAS