Qin Shi Huang, China’s first emperor and the visionary behind the world-famous Terracotta Army, has long been remembered for his unyielding pursuit of immortality. Now, newly authenticated evidence suggests that this legendary quest stretched farther than historians ever imagined. A stone inscription found high on the Tibetan Plateau records an expedition in 210 BCE to seek the elusive “elixir of life,” offering a striking new perspective on one of history’s most enigmatic rulers.

Discovery on the Tibetan Plateau

In June, researchers announced the discovery of a stone inscription in the Kunlun Mountains, near Gyaring Lake, more than 4,300 meters (14,000 feet) above sea level. Written in the ancient small seal script used during the Qin dynasty, the carving states:

“The emperor commanded Level Five Grand Master Yi to lead a group of alchemists here to collect yao.”

The word yao could mean medicinal herbs, minerals, or even the mythical elixir of life. The inscription also noted that the group traveled by carriage and reached Zhaling Lake in Qinghai during the third month of the 37th year of Qin Shi Huang’s reign.

For centuries, records documented Qin Shi Huang sending envoys eastward, possibly as far as Japan, to search for immortality. But no known texts mentioned a western expedition—until now.

📣 Our WhatsApp channel is now LIVE! Stay up-to-date with the latest news and updates, just click here to follow us on WhatsApp and never miss a thing!!

Scientific Authentication

The discovery sparked immediate debate, with skeptics questioning whether the inscription could be a modern forgery. Traveling to such harsh, high-altitude terrain in 210 BCE seemed improbable to some scholars.

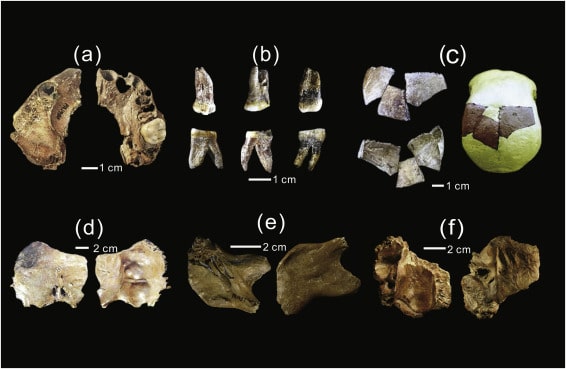

However, the National Cultural Heritage Administration of China confirmed the carving’s authenticity following rigorous investigation. Using advanced equipment, scientists analyzed the stone’s mineral composition, tool marks, and weathering patterns. Their findings ruled out modern tampering:

Tool Marks: The chisel strokes matched flat-edged instruments typical of Qin-era technology.

Weathering Evidence: Secondary minerals inside the grooves showed natural aging consistent with more than 2,000 years of exposure.

Material Durability: The quartz sandstone, known for its resistance to erosion, preserved the inscription in remarkable condition.

Deng Chao, an official from the heritage body, emphasized that the largely intact stone filled gaps in the historical narrative, especially since it bore a date absent from other records.

Qin Shi Huang and His Obsession with Immortality

Qin Shi Huang (259–210 BCE), originally the King of Qin, became the first emperor to unify China in 221 BCE after centuries of warfare among rival states. His reign established the Qin dynasty (221–207 BCE), which laid the foundations of imperial China—centralized government, standardized writing, currency, and even road systems.

Yet beyond his political achievements, the emperor is equally remembered for his fear of death. Ancient chronicles describe how he consulted alchemists, consumed mercury pills, and sent expeditions across land and sea to search for the elixir of life. Ironically, many believe his pursuit of immortality contributed to his death—possibly from mercury poisoning—while on tour in eastern China in 210 BCE.

The Terracotta Army: A Symbol of Eternal Rule

Perhaps the most enduring testament to his obsession is the Terracotta Army, thousands of life-sized clay soldiers buried near his mausoleum in Xi’an. Designed to protect him in the afterlife, the vast underground complex includes warriors, horses, chariots, and even musicians—an eternal empire mirroring his earthly one.

The newly authenticated Tibetan inscription adds another layer to this legacy. It suggests that the emperor’s quest was even more ambitious, reaching the remote frontiers of his empire in search of mystical cures.

Scholarly Debate Continues

Not all experts are convinced. Some, like Peking University historian Xin Deyong, argue that the verification process must be more transparent. He has called for the release of the full scientific report and the names of the specialists involved, warning against accepting government authority alone as proof.

Meanwhile, international scholars such as Li Yuelin, a physicist at Argonne National Laboratory and president of the Seven Seas Institute of Chinese Calligraphy, have supported the findings. Li noted that the tool marks alone are strong evidence of Qin-era craftsmanship, though he acknowledged that skepticism will likely persist.

Why This Discovery Matters

If authentic, the inscription is the only known Qin-era carving preserved in its original location. It provides rare physical evidence of Qin Shi Huang’s expeditions and enriches our understanding of how far the empire’s ambitions stretched.

For historians, the stone is more than an artifact—it is a bridge between legend and fact. It shows how the emperor’s pursuit of immortality was not just a myth or metaphor but a tangible policy that mobilized officials, alchemists, and resources across vast distances.

Legacy of the Qin Dynasty

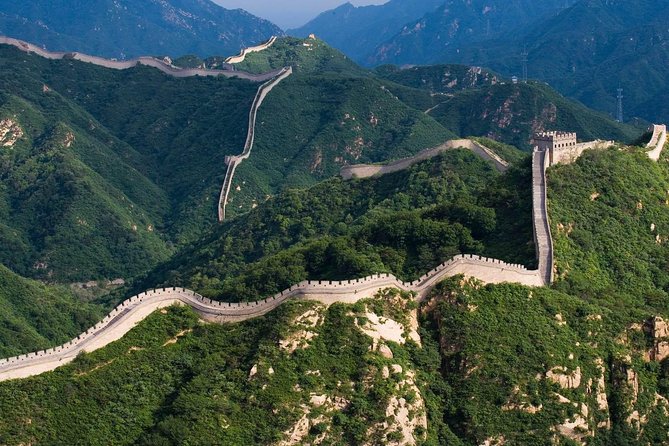

Although short-lived, the Qin dynasty transformed China forever. Its legalist philosophy emphasized strict laws and central authority, creating a framework that later dynasties would refine. Qin Shi Huang’s monumental projects, from the early construction of the Great Wall to his vast tomb complex, symbolized both his power and his desire to transcend mortality.

The Tibetan inscription now adds a surprising new chapter to this story. It suggests that Qin Shi Huang’s vision of eternal life was not confined to myth but actively pursued through daring, empire-spanning missions.

Conclusion

Over two millennia later, the emperor’s dream of immortality remains unfulfilled, but his legacy endures. From the Terracotta Warriors to mysterious inscriptions on remote mountainsides, Qin Shi Huang continues to captivate both scholars and the public.

The Tibetan carving reminds us that history is never static; new discoveries can reshape our understanding of the past. And in Qin Shi Huang’s relentless pursuit of eternal life, we see the timeless human desire to defy mortality—an ambition as fascinating today as it was in ancient China.

Cover Image Credit: Zhai Xiang