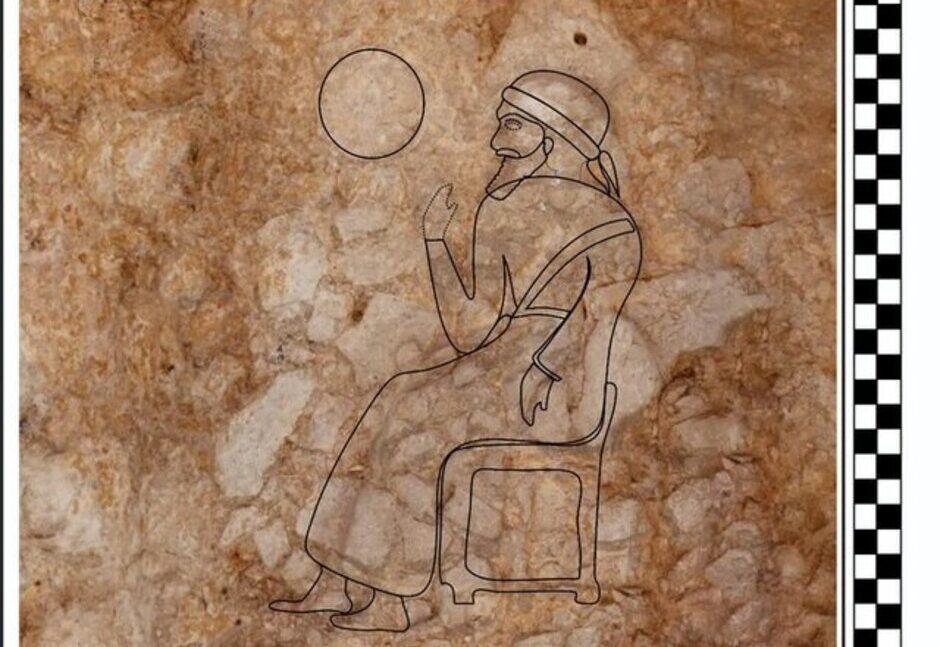

Archaeologists in Iran have unveiled what appears to be the smallest known Elamite rock relief ever discovered — a modest but iconographically significant carving found in Izeh, Khuzestan province, that may deepen our understanding of Elamite religious practice and its links with Mesopotamia.

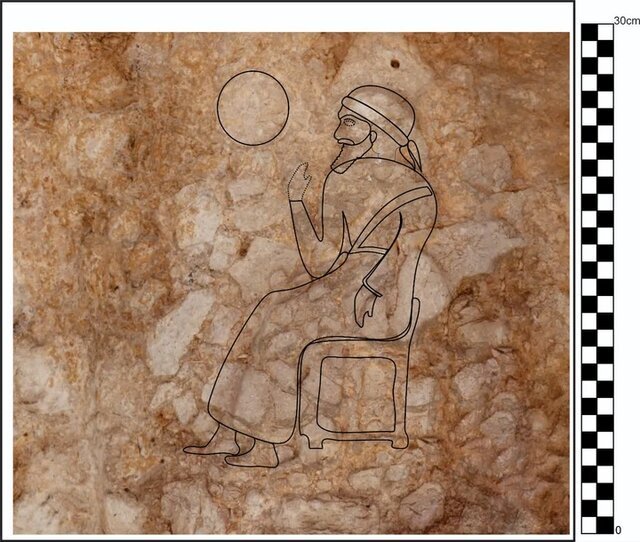

The relief — about the size of a human palm (approximately 26 cm in width) — depicts a seated king with his right hand elevated in prayer toward a solar disc. Above the monarch’s head is a finely carved disc symbolizing the sun god Nahhunte, a deity associated with solar and judicial powers. A stepped platform before the king likely served as an offering altar. The carving was made on a conglomerate (heterogeneous) rock surface rather than smoother stone, making it vulnerable to erosion and underlining the urgency of precise documentation.

Iran’s Ministry of Cultural Heritage, Tourism and Handicrafts announced the discovery, noting that this is the 13th Elamite bas-relief identified in the Izeh region. Scholars see it as an important key to revisit the religious and artistic traditions of Elam.

Context: Elam, Izeh, and Ancient Ayapir

Izeh (also historically known as Ayapir or in some sources Alhak/Elahak) lies in southwestern Iran’s Khuzestan and sits among a cluster of rock reliefs and cultic sites carved into the highland valleys. Some sources identify Izeh itself with the name Ayapir, tying this locale to the relief tradition.

According to the excavation team, the region of ancient Ayapir (sometimes called Elahak in local sources) functioned as a semi-independent city or polity under broader Elamite hegemony during the Middle Elamite period (c. 1500–1000 BC). The site’s strategic location, water resources, and concentration of archaeological traces made it politically and religiously significant in antiquity.

📣 Our WhatsApp channel is now LIVE! Stay up-to-date with the latest news and updates, just click here to follow us on WhatsApp and never miss a thing!!

Notably, in later centuries, a local ruler named Hanni of Ayapir (c. 7th–6th century BC) is known from inscriptions to have sponsored multiple reliefs in the Izeh valley (such as those at Kul-e Farah). Hanni styles himself in some reliefs as “kutur of Ayapir” and a subordinate to greater Elamite kings, such as Shutur-Nahhunte. Thus, Ayapir enjoyed a role in the regional relief tradition, bridging local cultic practices and royal symbolism.

While Ayapir’s earlier status is less documented, the recent discovery suggests that its religious functions may stretch further back than previously assumed. The new relief may be among the earliest in situ testimonies of solar-justice worship in the area.

Iconography, Symbolism, and Cultural Links

Though diminutive in scale, the newly discovered relief summarizes major themes in Elamite religious art. The king’s prayer posture, elevated hand, and proximity to a solar disc signal a ritual connection to divine authority and cosmic order. The choice of Nahhunte, a solar-justice deity, emphasizes the king’s role as an earthly executor of cosmic justice.

Comparative study of other Elamite reliefs (such as those at Kul-e Farah, Khong Ajdar, Shahsavar) reveals compositional parallels in the alignment of figures, altars, and solar motifs. The visual vocabulary echoes Mesopotamian iconography of sun gods and justice deities, possibly reflecting cultural exchange or adaptation.

Because this carving is executed on conglomerate rock rather than uniform stone surfaces, it is particularly exposed to weathering. The team emphasizes using laser scanning, photogrammetry, and careful conservation to preserve the fragile relief.

Beyond the immediate artistic import, the carving may prompt a reevaluation of how early Elamite rulers projected theocratic legitimacy, combining solar motifs with justice symbolism. Scholars may revisit assumptions about religious centralization in Elam and how it paralleled or diverged from Mesopotamian models of kingship.

Why This Tiny Relief Matters for Elamite History

Despite its small size, the relief has a disproportionate significance. It may push back the earliest appearance of visual solar-justice worship in the Elamite world, especially in a peripheral center such as Ayapir. The find bolsters the view that rock reliefs were key media for expressing royal and religious ideology in the highland corridors of Elam.

Going forward, comparative analysis with Elamite inscriptions, other reliefs, and Mesopotamian parallels will be essential. Establishing a precise chronology — through stylistic typology, geological analysis, or even microchemical dating — will help place this relief within the broader evolution of Elamite art. Monitoring how the king’s gesture, altar design, and solar disk motifs relate to known reliefs (e.g. Kul-e Farah) may yield insights into local workshops or religious schools.

Moreover, the presence of such a relief in the zone of Ayapir suggests that smaller, previously overlooked reliefs might exist in the Izeh valley. Systematic surveying using remote sensing, lidar scanning of cliffs, and targeted fieldwork may reveal additional minor carvings whose iconographic stakes are high.

Finally, in conservation terms, the use of high-resolution 3D scanning and digital archiving is indispensable for preserving the work against erosion. The team’s early focus on documentation may permit later restoration or virtual reconstructions — a lifeline for a relief carved on a delicate conglomerate surface.

Conclusion

This newly identified Elamite bas-relief in Izeh is small in scale but rich in implication. It draws a fresh line into the spiritual geography of Elam, reaffirming the religious significance of Ayapir and the enduring role of solar-justice symbolism. As study and preservation progress, this “hand-sized” king may emerge as a powerful interlocutor in Elam–Mesopotamia dialogues and in our broader understanding of early Iranian highland polity.