Ancient Mesopotamian bricks reveal the details of a curious strengthening of the Earth’s magnetic field, according to a new study involving University College London researchers.

Over a 500-year period beginning just over 3,000 years ago, traces of this perplexing strength have been discovered from China to the Atlantic Ocean, and they stand out more the closer they are to what is now Iraq. Until now, however, evidence from the region itself has been scarce and poorly dated.

The research, which was published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences on Monday, is based on archaeomagnetic techniques, which involve extracting information about the strength and direction of the Earth’s magnetic field from ancient objects.

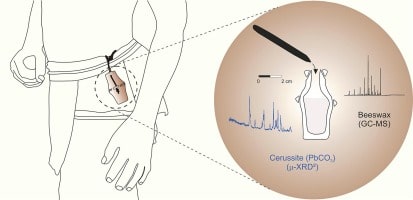

In order to test field strength, researchers employed ancient bricks containing iron oxide from Mesopotamia, which includes parts of modern-day Iraq. They were able to obtain a ratio between the object’s magnetic charge under laboratory conditions and in the past by methodically removing the ancient magnetic signature from small fragments of the bricks through heating and cooling, reheating the bricks, and replacing the magnetic field with one created in the lab.

This told researchers that these bricks were fired at a time when the Earth’s magnetic field was more than one and a half times what it is today, during a period known as the Levantine Iron Age geomagnetic anomaly.

📣 Our WhatsApp channel is now LIVE! Stay up-to-date with the latest news and updates, just click here to follow us on WhatsApp and never miss a thing!!

Professor Mark Altaweel of University College London is studying the exceptional strength of the magnetic field in the Middle East around 3,000 years ago, known as the Levantine Iron Age geomagnetic Anomaly. “We often depend on dating methods such as radiocarbon dates to get a sense of chronology in ancient Mesopotamia. However, some of the most common cultural remains, such as bricks and ceramics, cannot typically be easily dated because they don’t contain organic material,” Altaweel said in a statement.

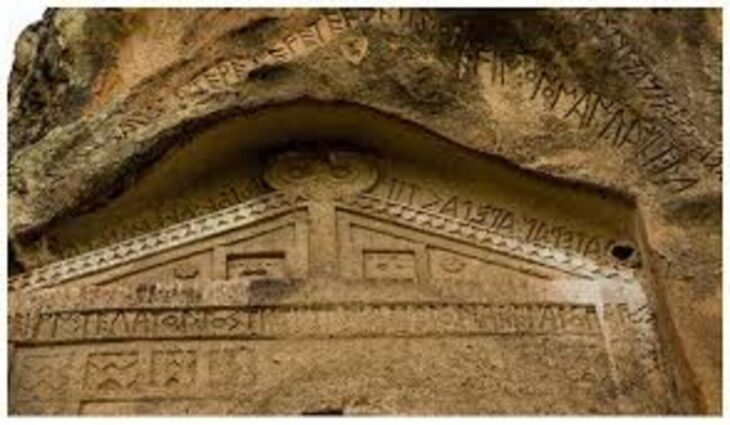

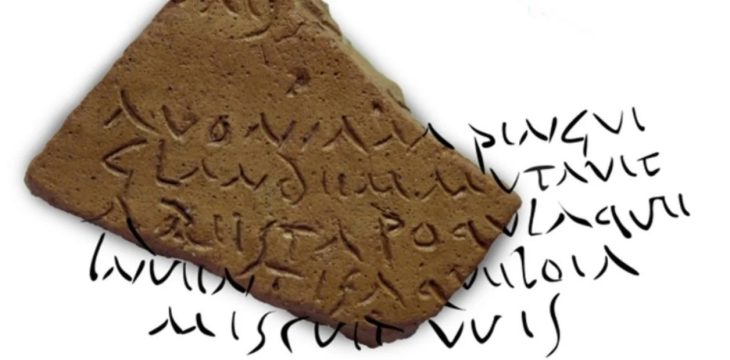

However, Altaweel and colleagues have located 32 Mesopotamian clay bricks, each inscribed with the name of one of 12 kings, presumably the ruler at the time they were made. These bricks also include iron oxide grains that retain the direction and strength of the magnetic field they were in when they were fired. Depending on the length of a king’s reign, and how well we know its timing, the inscriptions can be a much more precise record than carbon dating, which has uncertainties of decades or centuries.

The grains’ magnetism was measured by chipping fragments weighing 2 grams (0.07 ounces) off the bricks that were then tested with a magnetometer.

The results confirm the field was almost twice as strong in the area as it had been a thousand years before. Appropriately enough, the greatest shift Altaweel and colleagues found occurred during the reign of one king whose name remains familiar. the reign of Nebuchadnezzar II from 604 to 562 BCE, the Earth’s magnetic field seemed to change dramatically over a relatively short period of time, adding evidence to the hypothesis that rapid spikes in intensity are possible.

The work has proven more immediately beneficial to historians. There are detailed records of the order of the 12 kings and the lengths of their reigns, but debate continues as to when the sequence began and ended. The team provided support for one of the competing timelines proposed by historians, known as the Low Chronology, by comparing the fields recorded in the bricks with those measured using other methods.

This technique isn’t just valuable to archaeologists: It also might be a boon for geologists desperate to understand Earth’s changing magnetic field. These techniques allow scientists to peer back in time to before they began taking direct measurements of the magnetic field.

Such anomalies are not a thing of the past. The South Atlantic Anomaly (SAA) is believed to be millions of years old, but it still exists today. In the absence of a comparable dating method, scientists have tracked changes in the strength of the SAA 800-500 years ago by measuring ash from burned huts in the area at the time.

Cover Photo: : Slemani Museum