A new interdisciplinary study suggests that the Menga dolmen—one of Europe’s largest Neolithic monuments—did not lose its symbolic importance with the end of prehistory. Genetic, archaeological, and historical evidence indicates that two individuals buried at the site during the medieval Islamic period were intentionally placed within the monument, pointing to a deliberate reuse of a structure already thousands of years old.

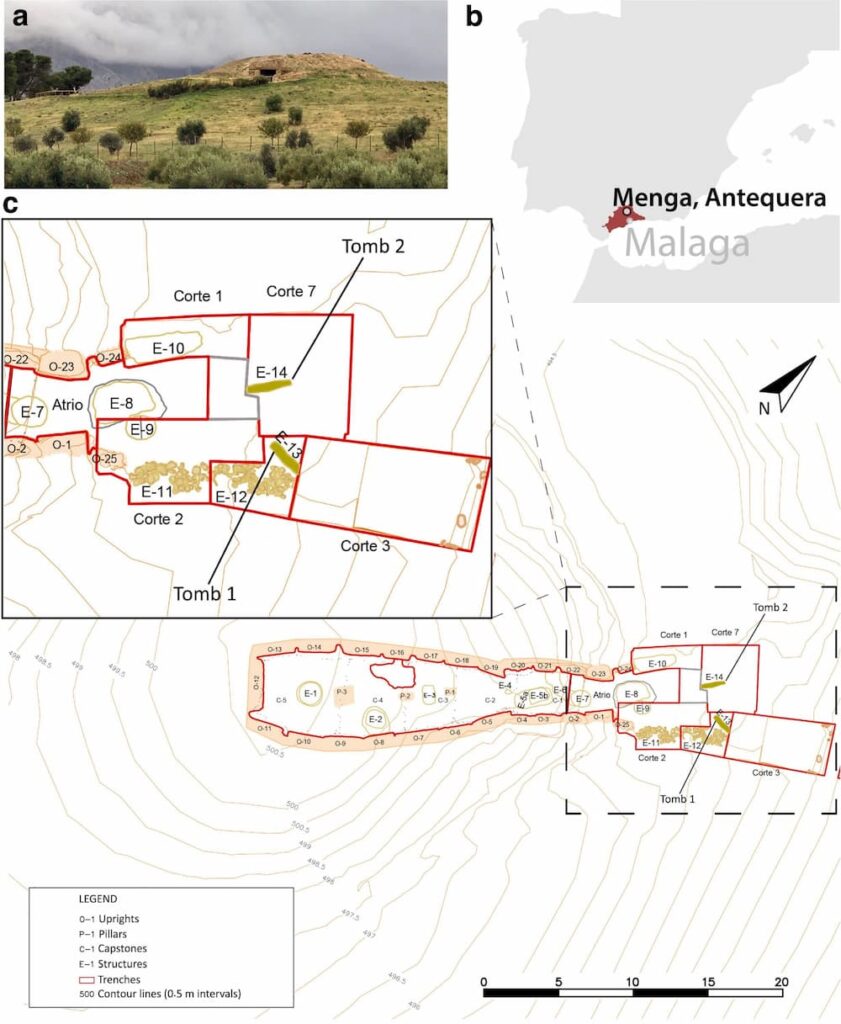

More than five millennia ago, Neolithic builders hauled enormous stone slabs across the plains of southern Iberia to create the Menga Dolmen, one of the largest and most enigmatic megalithic monuments in Europe. Rising from the landscape near Antequera, the structure predates Stonehenge and the Egyptian pyramids. Yet its story did not end in prehistory.

New research reveals that Menga was drawn back into human ritual life more than 4,000 years after its construction—when two individuals were deliberately buried within its atrium during the early medieval period. Their graves, aligned with the monument’s ancient axis, raise profound questions about memory, sacred landscapes, and cultural continuity in Islamic-era Iberia.

A multidisciplinary study published in Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports combines archaeology, radiocarbon dating, historical analysis, and ancient DNA to reconstruct the identities—and possible meanings—behind these unexpected burials.

A Monument Older Than History, Reused by History

Constructed in the fourth millennium BCE, the Menga dolmen is part of a UNESCO World Heritage landscape famed for its colossal architecture and precise orientation. Unlike most European megaliths, Menga does not face the rising sun but instead aligns with a natural rock formation, suggesting a worldview rooted as much in landscape symbolism as in astronomy.

📣 Our WhatsApp channel is now LIVE! Stay up-to-date with the latest news and updates, just click here to follow us on WhatsApp and never miss a thing!!

Archaeological evidence shows that the monument’s significance endured long after the Neolithic period. Over the centuries, Menga was revisited, modified, and reinterpreted—by Bronze Age communities, Iron Age groups, Romans, and eventually medieval inhabitants of Al-Andalus.

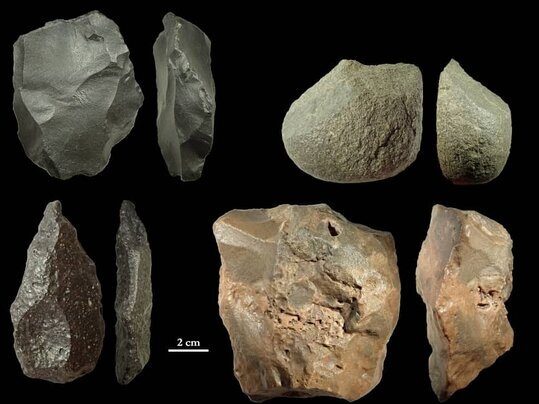

In 2005, excavations in the dolmen’s atrium uncovered two human burials. Both individuals were over 45 years old at death and were interred without grave goods. Radiocarbon dating places their deaths between the 8th and 11th centuries CE, spanning the early centuries of Islamic rule in southern Iberia.

What set these burials apart was not just their location, but their orientation.

Bodies Aligned With Stone and Faith

Both individuals were buried in a prone position, lying face down, with their heads resting on the right side. Their faces were oriented southeast—toward Mecca—consistent with Islamic funerary practices. Yet their bodies were also aligned precisely along the dolmen’s prehistoric axis of symmetry, a choice without parallel in nearby Islamic cemeteries.

This deliberate alignment appears to acknowledge the monument itself as a meaningful presence, not merely a convenient shelter or ruin.

Such a gesture complicates straightforward interpretations. Islamic burials in Al-Andalus typically followed standardized orientations but did not reference prehistoric architecture in this symbolic way. Why, then, were these individuals deliberately aligned with a monument already ancient by medieval standards?

To address this question, researchers turned to genetics.

Extracting DNA From a Hostile Climate

Recovering ancient DNA in the Mediterranean is notoriously difficult. Heat, soil chemistry, and microbial activity degrade genetic material rapidly. In the case of Menga, DNA preservation was exceptionally poor. Less than one percent of the recovered genetic material was human, and most fragments were extremely short.

Using advanced enrichment techniques targeting more than 1.2 million specific genetic markers, researchers succeeded in reconstructing the genome of one individual, known as Menga1. The second individual’s DNA was too contaminated for reliable analysis.

Despite these limitations, the genetic results proved remarkably informative.

A Man of Many Shores

The genetic profile of Menga1 reflects the deep interconnectedness of the medieval Mediterranean.

Along his paternal line, he belonged to Y-chromosome haplogroup R-P312, a lineage common in western Europe and present in Iberia since at least the Chalcolithic period. His maternal lineage, mitochondrial haplogroup V34a, is also European—but with a notable twist. His specific genetic signature shares mutations with modern populations in Morocco and Algeria, hinting at trans-Mediterranean connections.

Autosomal DNA analysis revealed an even richer picture. Statistical modeling suggests that Menga1’s ancestry was composed of roughly 44 percent local Iron Age Iberian heritage, 18 percent North African ancestry, and 37 percent Levantine-related ancestry. This genetic mosaic mirrors patterns seen in other Roman and early medieval individuals from Iberia and Italy.

Such diversity is not surprising. For centuries, Iberia was embedded in Mediterranean trade networks shaped by Phoenician, Roman, and later Islamic expansion. After the Islamic conquest of 711 CE, movement between Iberia, North Africa, and the eastern Mediterranean intensified, leaving enduring genetic traces.

Importantly, the researchers caution against equating genetic ancestry with religious identity. DNA does not encode belief.

Islamic Burial—or Something More?

Archaeologically, the Menga burials are broadly compatible with Islamic practice: simple graves, no grave goods, and orientation toward Mecca. Yet their symbolic engagement with a Neolithic monument is highly unusual.

The study situates this anomaly within a wider pattern. Across Iberia, prehistoric monuments were occasionally reused during the Islamic period. At the Alberite I dolmen in Cádiz, at least seventeen individuals were buried in Islamic fashion during the Almohad period. Similar practices have been documented in Portugal, where Islamic and Christian burials appeared within Chalcolithic enclosures.

Why did medieval communities return to these ancient places?

Historical sources from the Islamic world describe fascination with pre-Islamic ruins, often seen as talismanic or imbued with hidden power. In rural landscapes especially, certain locations may have retained a reputation for sanctity that transcended religious boundaries.

The researchers propose that Menga may have functioned as a qubba or marabout—a shrine or retreat associated with holy individuals or ascetics. Its monumental scale, visibility, and isolation outside medieval Antequera would have made it an ideal place for spiritual withdrawal or venerated burial.

A Biography Spanning Five Millennia

What emerges from this study is not simply the story of two medieval individuals, but the extended biography of a monument.

Menga was not a relic frozen in the past. It was a living landmark—reinterpreted, re-sacralized, and woven into new belief systems across thousands of years. The medieval burials aligned with its axis suggest a conscious engagement with deep time, an acknowledgment that the past still mattered.

By combining genetics, archaeology, and historical context, the research demonstrates how sacred landscapes can persist beyond cultural and religious transformations. The fragile DNA recovered from Menga has added a new chapter to the monument’s long life—one that connects Neolithic builders, medieval communities, and modern science in a single narrative arc.

In doing so, it reminds us that monuments do not simply endure. They continue to mean.

Silva, M., García Sanjuán, L., Fichera, A., Oteo-García, G., Foody, M. G. B., Fernández Rodríguez, L. E., Navarrete Pendón, V., Bennison, A. K., Pala, M., Soares, P., Reich, D., Edwards, C. J., & Richards, M. B. (2026). Genetic and historical perspectives on the early medieval inhumations from the Menga dolmen, Antequera (Spain). Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports, 69, 105559. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jasrep.2025.105559

Cover Image Credit: View inside from the entrance. Wikipedia Commons