The discovery of a Maya salt-making compound preserved beneath the mangrove peat of southern Belize is transforming our understanding of ancient Maya industry and daily life. Hidden for over a thousand years under the waters of the Punta Ycacos Lagoon, this remarkably intact site reveals how Maya families once produced, traded, and lived around the “white gold” of their world—salt.

Unearthed by archaeologists Dr. Heather McKillop and Dr. E. Cory Sills, the find sheds light on an entire network of coastal households that specialized in salt production, challenging long-held assumptions about “invisible” Maya settlements and the sophistication of their maritime economy.

An Ancient Maya Household Frozen in Time

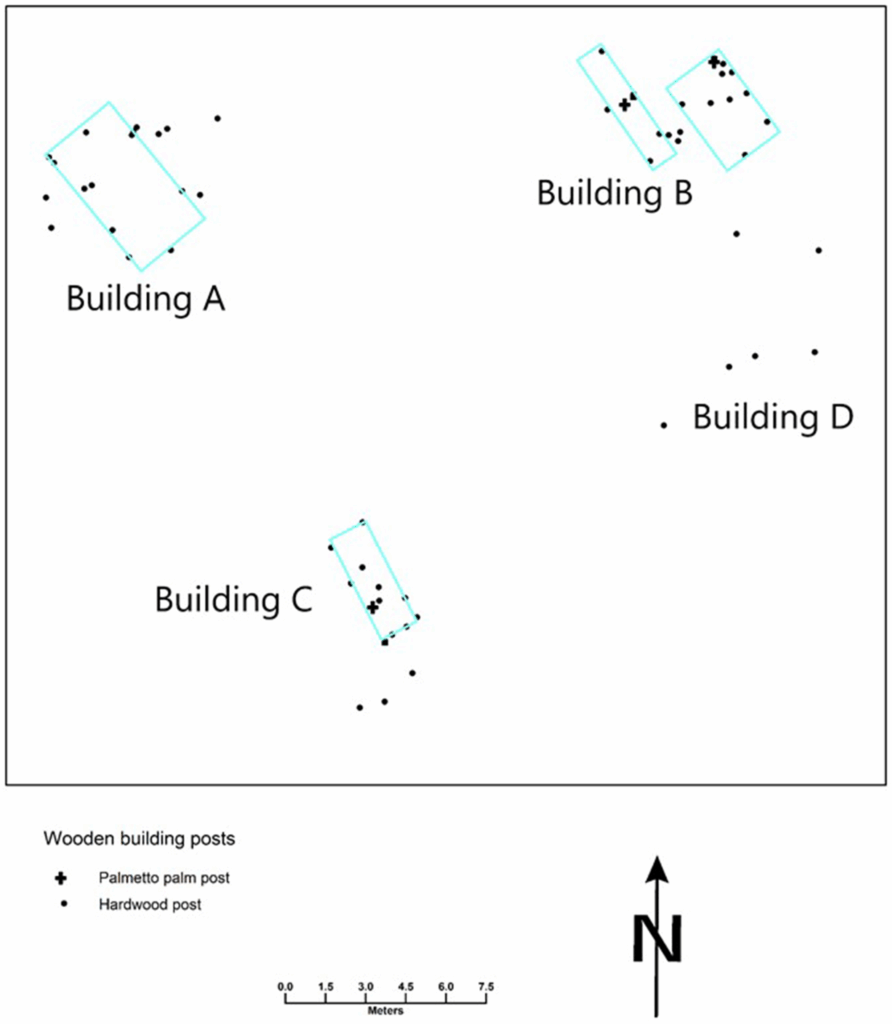

The Cho-ok Ayin site dates to the Late Classic period (AD 550–800) and was discovered preserved beneath layers of mangrove peat on the lagoon’s sea floor. Archaeologists found 56 hardwood posts and three palmetto-palm posts, perfectly preserved in anaerobic peat deposits that prevented decay. These posts outlined four pole-and-thatch buildings, representing a complete Maya household compound—a type of settlement usually lost to time because such wooden architecture rarely survives.

“The preservation of the wooden buildings and wooden objects at the submerged Classic Maya sites in Punta Ycacos Lagoon has not been found elsewhere along the coasts of Belize and the Yucatan,” Dr. McKillop explained. “The mangrove peat created the ideal conditions for preservation, allowing us to see wooden architecture that is normally invisible in archaeology.”

The “Invisible Sites” of the Ancient Maya

Traditionally, archaeologists identify Maya settlements using mound surveys and airborne lidar scans, which detect stone-based structures and elevated platforms. However, pole-and-thatch dwellings—common among both ancient and modern Maya communities—often decay completely, leaving no mounds or foundations. Such settlements, known as “invisible sites,” are therefore absent from most archaeological maps and population models.

📣 Our WhatsApp channel is now LIVE! Stay up-to-date with the latest news and updates, just click here to follow us on WhatsApp and never miss a thing!!

The Cho-ok Ayin discovery challenges these limitations. Despite lacking monumental architecture, the site was clearly inhabited and productive. Mapping of the posts revealed a residential building (Building A), two salt-production kitchens (Buildings B and C), and a fourth structure (Building D) likely used for brine enrichment—the process of increasing the salt content of lagoon water before boiling.

Salt: The White Gold of the Maya

Salt was a vital resource for the ancient Maya, used not only for food preservation and trade but possibly as a form of currency. The Paynes Creek Salt Works, where Cho-ok Ayin is located, was part of a vast network of salt-producing households that supplied inland Maya cities.

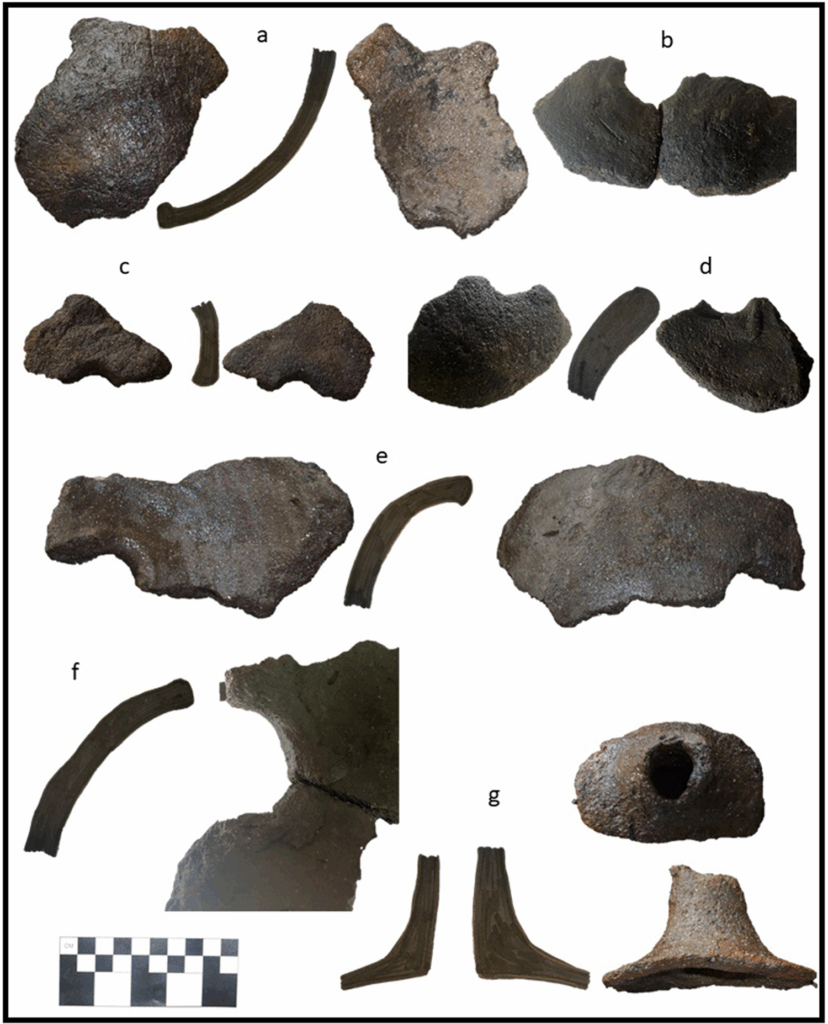

At Cho-ok Ayin, researchers found clay funnels, brine-boiling pots, and briquetage (salt-making pottery). The inhabitants enriched saline water by pouring it through salt-rich sediments held in raised containers. The enriched brine was then boiled in ceramic vessels over wood fires until the water evaporated, leaving behind crystallized salt. Some of this salt hardened into cakes within the pots, which were then broken to extract the finished product—similar to modern salt-making practices in Sacapulas, Guatemala.

“The Maya here produced salt cakes for trade,” said Dr. McKillop. “They likely exchanged these with inland communities for maize, pottery, and obsidian.”

Trade, Tools, and Everyday Life

Far from being isolated or impoverished, the residents of Cho-ok Ayin participated in long-distance trade networks across Mesoamerica. Artifacts recovered from the site include Belize Red pottery from the upper Belize River valley, obsidian blades from highland Guatemala, chert tools from northern Belize, and even a jadeite axe fragment from the Motagua River valley. These findings show that even households built of humble materials were economically active and regionally connected.

Other discoveries include ocarinas (musical figurine whistles) used in household rituals, paddle fragments likely associated with canoe transport, and metate legs for grinding maize. Such objects paint a vivid picture of daily life—one of labor, trade, ritual, and community.

A Window into the Past—and the Future

Radiocarbon dating of the posts confirms construction between AD 650 and 700, placing Cho-ok Ayin firmly in the Late Classic era. Archaeologists estimate that about five people lived in this compound, engaged in salt production and small-scale trade. Without the unique underwater preservation, however, the site would have appeared as a population of zero in conventional surveys—highlighting how “invisible sites” distort our understanding of ancient Maya society.

The discovery also carries broader implications. Rising seas during the Holocene submerged vast stretches of the Belize coast, hiding entire communities beneath the lagoon’s mangrove mud. The same processes that preserved Cho-ok Ayin are a reminder of how modern sea-level rise could once again erase coastal heritage worldwide.

Rewriting the Archaeological Record

The Cho-ok Ayin site offers an unprecedented look at the wooden architecture and household economy of the Classic Maya. It demonstrates that pole-and-thatch homes—though archaeologically “invisible”—were vital centers of production and trade. The find also redefines how archaeologists estimate ancient populations and assess wealth distribution.

“Invisible Maya sites like Cho-ok Ayin challenge our assumptions about how many people lived and worked along the ancient coast,” McKillop noted. “They remind us that even the simplest structures can hold extraordinary stories about resilience, innovation, and connection.”

McKillop, H., & Cory Sills, E. (2025). Ancient Maya submerged landscapes and invisible architecture at the Ch’ok Ayin residential household group, Belize. Ancient Mesoamerica, 1–22. doi:10.1017/S0956536125000136

Cover Image Credit: A photo from the study shows archaeologists carefully marking the positions of preserved wooden posts with wire flags at the Ch’ok Ayin residential household group, documenting the precise layout of this submerged Maya salt-making compound. McKillop & Sills, 2025, Ancient Mesoamerica.