Hominins living at Gesher Benot Ya’akov 780,000 years ago liked their fish to be well cooked, Israeli researchers revealed Monday, in what they said was the earliest evidence of fire being used to cook.

Preparing food with heat or fire is an activity unique to humans. However, exactly when our ancestors started cooking has been a matter of controversy among archaeologists because it is difficult to prove that an ancient fireplace was used to prepare food, and not just for warmth.

According to a new study published in the journal Nature Ecology and Evolution, the first “definitive evidence” of cooking was by Neanderthals and early Homo sapiens 170,000 years ago.

The study, which pushes that date back by more than 600,000 years, is the result of 16 years of work by its first author Irit Zohar, an archaeologist at Tel Aviv University’s Steinhardt Museum of Natural History.

The discovery has implications for our understanding of how humans evolved, revealing that our so-called primitive forefathers were far more advanced than previously thought, according to the researchers. It also emphasizes the role of fishing versus hunting in human development, according to the authors.

📣 Our WhatsApp channel is now LIVE! Stay up-to-date with the latest news and updates, just click here to follow us on WhatsApp and never miss a thing!!

Gesher Benot Ya’akov (“Daughters of Jacob Bridge” in Hebrew) is situated on the Jordan River’s banks. It was once a rich, marshy area on the shores of the Hula paleo-lake, and hominins would return there for 100,000 years to hunt and feast on giant two-meter-long carps, elephants, and local fruits and plants.

Previously discovered burnt flint tools at Gesher suggested that the locals knew how to use fire. Still, scorched artifacts or sediments are often insufficient to tell us whether the fire was natural, accidental, or purposefully made and controlled and whether it was used for warmth, cooking, or garbage disposal.

But at Gesher, the excavators noticed something unusual, according to Dr. Irit Zohar, an archaeologist and marine biologist at Tel Aviv University’s Natural History Museum and Oranim Academic College. 40,000 fish remains were discovered in the same layers as the burnt flints, with more than 95 percent of them being teeth, according to Zohar, the study’s lead author.

What became of all the bones? The most likely explanation was that the fish had been cooked, as this softens the bones (which is why fish bones are frequently used to make gelatin). As a result, any bones that were left over would have quickly decomposed, leaving only the teeth for archaeologists to discover nearly a million years later.

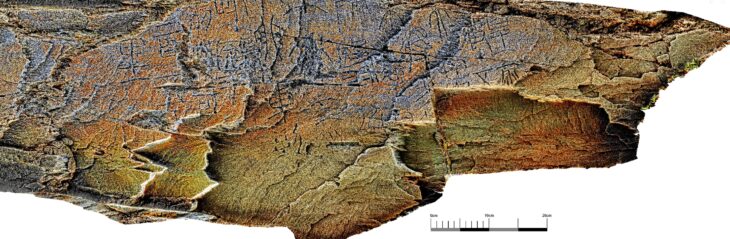

The teeth were examined using X-ray diffraction to examine the nanocrystals that make up the enamel in order to test this hypothesis. The manager of the X-ray lab at the Natural History Museum in London, Dr. Jens Najorka, explains that these crystalline structures enlarge when heated. Najorka reports that the crystals in the enamel on the fish teeth from Gesher did, in fact, exhibit a slight size expansion consistent with the application of low-to-moderate heat, less than 500 degrees Celsius.

According to Zohar, the low temperature is significant because it indicates cooking, whereas a higher temperature would have simply meant that the leftovers were burned by being thrown into the fire, either as fuel or as a method of waste disposal.

Previous research had shown that the burnt flints found at Gesher were not distributed randomly, as if they had been burned in a natural bush fire, but were found in dense concentrations, likely marking the locations where hominins purposefully and repeatedly made hearths and lit their fires over tens of thousands of years.

According to Naama Goren-Inbar, an emerita professor at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem and the archaeologist in charge of the Gesher dig, the findings of the latest study “only reinforce the conclusion that the locals could control fire.”

Cover Photo: Illustration of hominins cooking fish. Ella Maru / University of Tel Aviv