Long before the pyramids rose above the Nile or the great temples of Mesopotamia carved their mark into the ancient world, a community in the hills overlooking modern Amman created something astonishing: a population of ghostlike statues with staring eyes and double faces, carefully buried beneath the floors of their abandoned homes. Archaeologists now consider Ain Ghazal—often called “Jordan’s Çatalhöyük” or even “Jordan’s Göbeklitepe”—one of the most remarkable Neolithic sites in the world, a birthplace of some of humanity’s earliest symbolism, ritual, and social complexity.

First discovered in the 1970s during highway construction, Ain Ghazal quickly proved to be a settlement that would reshape our understanding of Pre-Pottery Neolithic culture. Rescue excavations led by Gary Rollefson revealed that this community thrived between 7,250 and 5,000 BCE, spanning the Middle and Late Pre-Pottery Neolithic B (MPPNB and LPPNB). Over these 2,000 years, the inhabitants pioneered farming, domesticated animals, plastered their homes with white lime, and practiced elaborate burial rituals involving skull removal and plastered faces.

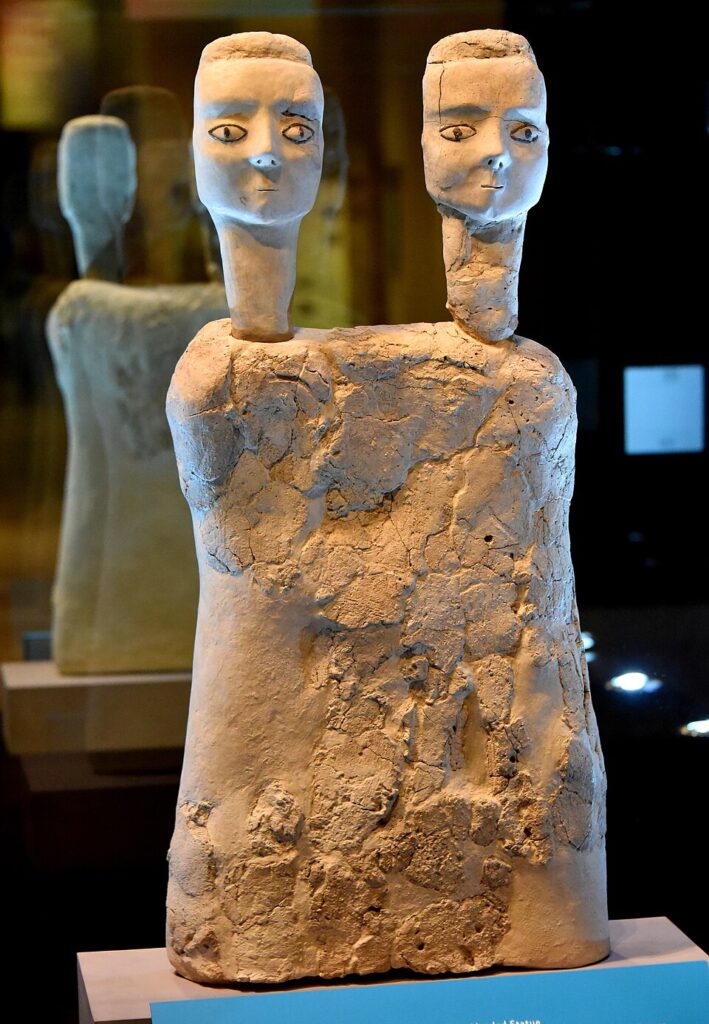

Yet what sets Ain Ghazal apart—and continues to captivate scholars and the public alike—are its two caches of monumental human statues, crafted from lime plaster and reeds, and buried with ceremonial care around 6,750–6,500 BCE.

They remain among the oldest known large-scale human statues in the world.

A City of the Living—and the Dead

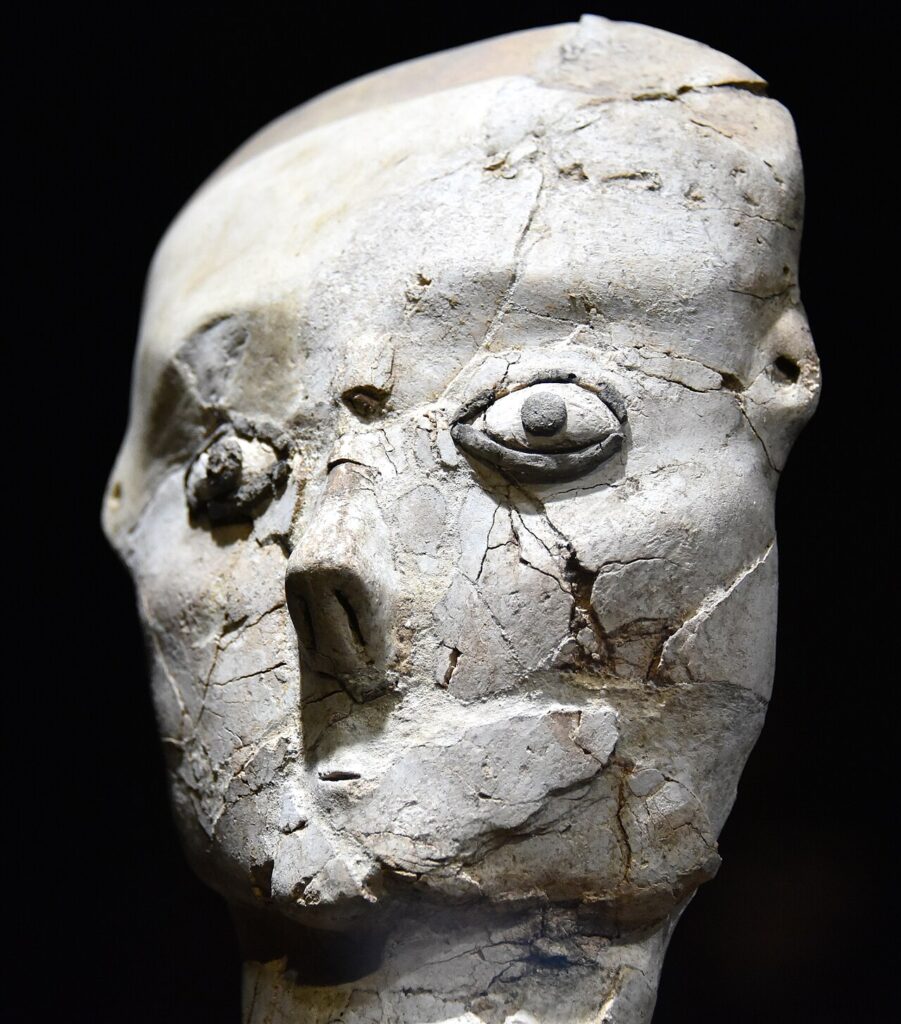

Life at Ain Ghazal was a blend of innovation and ritual. Archaeologists uncovered the remains of domesticated sheep and pigs, fields of wheat and barley, jars once filled with lentils and chickpeas. But beneath the floors of houses, they found something more intimate: flexed burials with skulls removed, later coated with plaster and molded into lifelike faces. Eyes were painted wide or closed, cheeks shaped with care, and sometimes pigments added.

📣 Our WhatsApp channel is now LIVE! Stay up-to-date with the latest news and updates, just click here to follow us on WhatsApp and never miss a thing!!

These practices echo a deep spiritual world—one in which the lines between the living, the dead, memory, and identity were blurred. Some skulls were treated with such precision that scholars suggest the presence of ancestor veneration, or at the very least, a ritual system that used human remains as powerful social symbols.

But the statues—far larger, stranger, and more stylized—suggest something even more complex.

The Rise of the Ghost Statues

The first cache, dating to around 6,750 BCE, contained 25 statues, including 13 full figures and 12 one-headed busts. The second cache, nearly two centuries later, held seven statues, including two full figures and three rare two-headed busts.

All were anthropomorphic. All were deliberately buried. And all appear eerily lifelike—yet not quite human.

Their eyes are enormous and rimmed with bitumen. Their noses are small and upturned. Mouths are tiny, almost lipless. Bodies are thin, nearly flat, and genitalia are almost always absent. While some early statues display painted “garments,” the later ones grow taller, more rigid, and increasingly standardized.

The evolution is unmistakable: over 200–300 years, Ain Ghazal’s statues became less human and more otherworldly.

Scholars have proposed several interpretations:

- Ancestors of the Community

Because plastered skulls and statues share stylistic features, some believe the statues represent revered ancestors. But the lack of gender markers and the inclusion of two-headed figures challenge this view.

- Ritual “Ghosts”

In the 1990s, periodical Archaeology dubbed them “Ghosts of Ain Ghazal.” This name stuck—for good reason. Their skeletal noses, wide staring eyes, unnatural fingers and toes (sometimes six or seven), and flat, almost corpse-like bodies evoke an uncanny, liminal presence. Ethnographic parallels from ancient Mesopotamia describe substitute figures used in rituals to expel, appease, or embody spirits, prompting some scholars to wonder whether Ain Ghazal’s statues served similar purposes.

- Deities of an Early Near Eastern Pantheon

Other archaeologists argue the figures may be among the earliest representations of gods and goddesses. The two-headed busts echo twin deities known from Çatalhöyük, Hacılar, and later Mesopotamian iconography. One striking statue from Cache 1 shows a woman presenting her breasts—a pose associated with fertility goddesses throughout the ancient Near East. Comparisons from Anatolia to Syria support this interpretation, suggesting that Ain Ghazal may preserve one of the earliest expressions of a fertility cult linked to early farming communities.

These competing theories reveal just how ambiguous—and powerful—the statues are. Their meaning may lie in the intersection of all three: ancestors, ghosts, and gods, entwined in the symbolic imagination of a society experiencing the profound technological and emotional shifts that accompanied the birth of agriculture.

Why Bury the Statues?

Every statue from Ain Ghazal was found intentionally buried beneath abandoned homes. They were placed carefully, often oriented east–west, and generally in good condition at the time of interment. This suggests ritual retirement, perhaps after ceremonies tied to seasonal cycles, death and rebirth, or communal identity.

Their materials—reed and plaster—were perishable. Unlike stone statues meant to endure for centuries, these figures were meant to live briefly. Their burial may reflect a belief that once their ritual purpose was complete, they had to be “laid to rest,” just like the humans whose skulls were buried below the floors.

Some researchers even propose that these statues were “born,” “lived,” and then “died,” mirroring agricultural cycles and embodying early myths of dying and rising deities.

A Neolithic Legacy Still Coming into Focus

Ain Ghazal’s discovery transformed Jordan into one of the most important regions for understanding Neolithic religion and society. The site’s monumental plastic art parallels traditions found at Jericho and Nahal Hemar, but its scale far surpasses them. And its statues—especially the spectral two-headed busts—feature stylistic traits unseen anywhere else in the prehistoric world.

As researchers continue to study the settlement, its residue of ritual, and its ghostlike figures, Ain Ghazal is increasingly recognized as a cradle of communal symbolism, a crossroads where spirituality, social identity, and early monumental art first converged.

In a world where humanity had just begun building permanent homes, cultivating the land, and imagining its future, Ain Ghazal’s statues offer a haunting reminder: before writing or cities, people told stories in plaster and reed—stories of ancestors, spirits, gods, and the invisible forces shaping their lives.

Source

Grissom, C.A. 2000. “Neolithic statues from ‘Ain Ghazal: construction and form” AJA 104: 25-45.

Rollefson, G.O.; 1984. “Early Neolithic statuary from ‘Ain Ghazal (Jordan)” Mitteilungen der Deutsche Orient-Gesellschaft 116: 185-192.

Schmandt-Besserat, D. (1998). ‘Ain Ghazal “monumental” figures: A stylistic analysis. In G. O. Rollefson & Z. Kafafi (Eds.), Ain Ghazal excavation reports (pp. 319–330). American School of Oriental Research. (Reprinted in The Bulletin of the American School of Oriental Research, 310, 1–17.)

Cover Image Credit: Tarrad, M., Al-Omari, O., & Alrawashdeh, M. (2012). Natural stone in Jordan: Characteristics and specifications and its importance in interior architecture. Archaeological Science Journal, 720–727.