Hundreds of mummified bees inside their cocoons have been found on the southwest coast of Portugal, in a new paleontological site on the coast of Odemira.

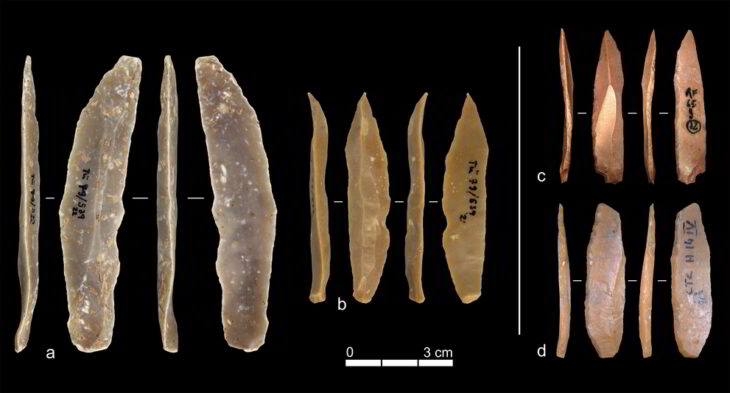

The discovery published in the international scientific journal Papers in Paleontology states that this method of fossilization is extremely rare and normally the skeleton of these insects rapidly decomposes since it has a chitinous composition, which is an organic compound.

About 2975 years ago, Pharaoh Siamun reigned in Lower Egypt; in China the Zhou Dynasty elapsed; Solomon was to succeed David on the throne of Israel; in the territory that is now Portugal, the tribes were heading towards the end of the Bronze Age. In particular, on the southwest coast of Portugal, where is now Odemira, something strange and rare had just happened: hundreds of bees died inside their cocoons and were preserved in the smallest anatomical detail.

“The degree of preservation of these bees is so exceptional that we were able to identify not only the anatomical details that determine the type of bee, but also its sex and even the supply of monofloral pollen left by the mother when she built the cocoon”, says Carlos Neto de Carvalho, scientific coordinator of Geopark Naturtejo, a UNESCO Global Geopark, and collaborating researcher at Instituto Dom Luiz, at the Faculty of Sciences of the University of Lisbon – Ciências ULisboa (Portugal).

Carlos Neto de Carvalho says that the project identified four paleontological sites with a high density of bee cocoon fossils, reaching thousands in a square measuring one meter. These sites were found between Vila Nova de Milfontes and Odeceixe, on the coast of Odemira, a municipality that gave strong support to the execution of this scientific study, allowing its dating by carbon 14.

📣 Our WhatsApp channel is now LIVE! Stay up-to-date with the latest news and updates, just click here to follow us on WhatsApp and never miss a thing!!

“With a fossil record of 100 million years of nests and hives attributed to the bee family, the truth is that the fossilization of its user is practically non-existent”, reinforces Andrea Baucon, one of the co-authors of the present work, a paleontologist at the University of Siena (Italy).

The cocoons now discovered, produced almost three thousand years ago, preserve as in a sarcophagus the young adults of the Eucera bee that never got to see the light of day. This is one of about 700 species of bees that still exist in mainland Portugal today. The newly discovered paleontological site shows the interior of the cocoons coated with an intricate thread produced by the mother and composed of an organic polymer. Inside, you can sometimes find what’s left of the monofloral pollen left by the mother, with which the larva would have fed in the first times of life. The use of microcomputed tomography allowed to have a perfect and three-dimensional image of the mummified bees inside sealed cocoons.

Bees have more than twenty thousand existing species worldwide and are important pollinators, whose populations have suffered a significant decrease due to human activities and which has been associated with climate change. Understanding the ecological reasons that led to the death and mummification of bee populations nearly three thousand years ago could help to understand and establish resilience strategies to climate change. In the case of the southwest coast, the climatic period that was experienced almost three thousand years ago was marked, in general, by colder and rainier winters than the current ones.

“A sharp decrease in night temperature at the end of winter or a prolonged flooding of the area outside the rainy season could have led to the death, by cold or asphyxiation, and mummification of hundreds of these small bees”, reveals Carlos Neto de Carvalho.

The Naturtejo Geopark of Meseta Meridional, which is part of the UNESCO world network, includes the municipalities of Castelo Branco, Idanha-a-Nova, Oleiros, Penamacor, Proença-a-Nova and Vila Velha de Ródão (in the district of Castelo Branco) and Nisa (Portalegre).

FACULTY OF SCIENCES OF THE UNIVERSITY OF LISBON

Cover İmage: Image taken under binocular lens, corresponding to specimen details of the dorsum. This specimen was extracted from the sediment filling a cocoon. Photo: Andrea Baucon.