A groundbreaking archaeological discovery in eastern Türkiye is reshaping historians’ understanding of the ancient Kingdom of Sophene, a little-known Hellenistic-era polity that once stood at the crossroads of Anatolian, Iranian, and Greek civilizations. The recent discovery of a Middle Aramaic inscription at Rabat Fortress, in modern-day Tunceli province, provides the first direct written evidence of local elites in Sophene and offers rare insight into how power, identity, and language intersected in this mountainous frontier kingdom.

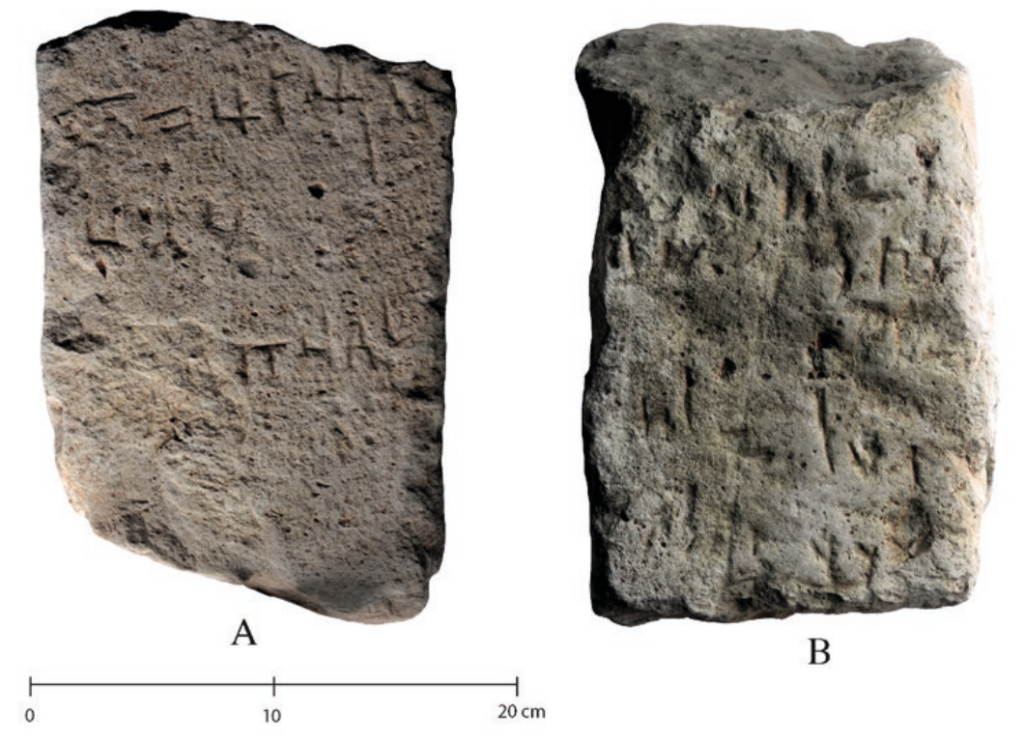

The inscription, carved in stone and dated to the second century BCE, was found during archaeological surveys at Rabat Fortress, a strategically located stronghold overlooking deep valleys and rocky gorges. Scholars describe the find as a “once-in-a-generation discovery,” as it marks the first known local Aramaic inscription from Sophene, a kingdom previously known almost entirely through external Greek and Roman sources.

A Forgotten Kingdom Between Empires

Sophene occupied a rugged landscape east of the Euphrates River, roughly corresponding to today’s western Tunceli and Elazığ provinces. Bordered by the Munzur and Taurus Mountains, the region’s difficult terrain allowed local rulers to maintain relative autonomy while navigating shifting allegiances between major powers such as the Achaemenid Persians, Seleucid Greeks, and later the Romans.

Until now, most historical reconstructions of Sophene focused on its central dynasty, especially rulers claiming descent from the powerful Orontid lineage, a family associated with Achaemenid imperial heritage. What was missing was the voice of local elites—the regional lords who governed micro-regions and acted as intermediaries between royal authority and rural communities.

The Rabat Fortress inscription changes that.

📣 Our WhatsApp channel is now LIVE! Stay up-to-date with the latest news and updates, just click here to follow us on WhatsApp and never miss a thing!!

The Inscription That Rewrites History

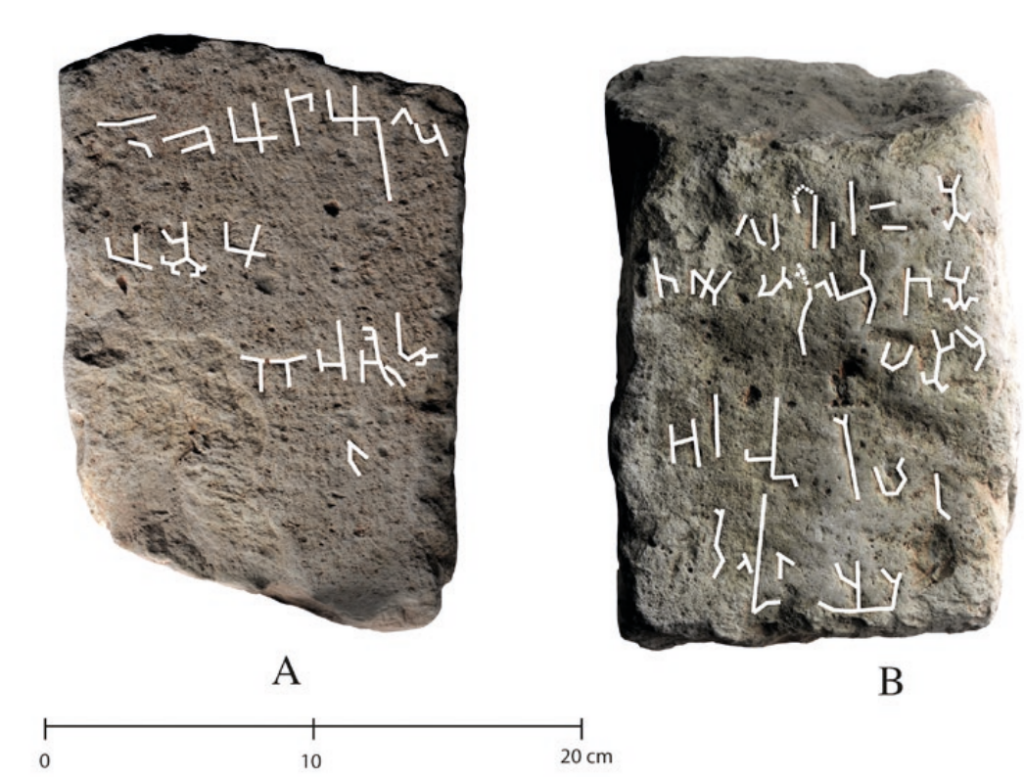

The Aramaic text was discovered reused as a building stone (spolia) in a village stable near Rabat Fortress, having survived centuries of earthquakes, rebuilding, and reuse. Once removed and studied, researchers found that the stone bears inscriptions on two sides, written in a unique local adaptation of Middle Aramaic script, now identified as a distinct “Sophene variant”.

The funerary inscription commemorates a local lord (RB, “lord”), a member of Sophene’s political elite, and explicitly references the “House of Orontes”, confirming the individual’s allegiance to the ruling dynasty. This is the clearest evidence yet that local elites in Sophene consciously used Orontid lineage as a source of legitimacy.

Even more striking is the possible mention of King Mithrobouzanes, a Sophenean ruler known from numismatic and classical sources and dated to the early second century BCE. If confirmed, this would directly link Rabat Fortress to the royal court and firmly anchor the site within Sophene’s political network.

Language, Power, and Identity

The use of Aramaic—rather than Greek—reveals a great deal about Sophene’s cultural orientation. While Greek was the dominant language of the Hellenistic world, Aramaic functioned as a prestige administrative and ideological language, deeply connected to Persian imperial traditions.

The inscription also employs an Iranian calendar system and possibly invokes the deity Mithra, reinforcing the idea that Sophene’s elites positioned themselves between Iranian and Hellenistic traditions rather than fully embracing either.

“This discovery shows that Aramaic was not just a leftover imperial language,” researchers note, “but an active medium through which Sophene’s local elites expressed authority, memory, and political belonging.”

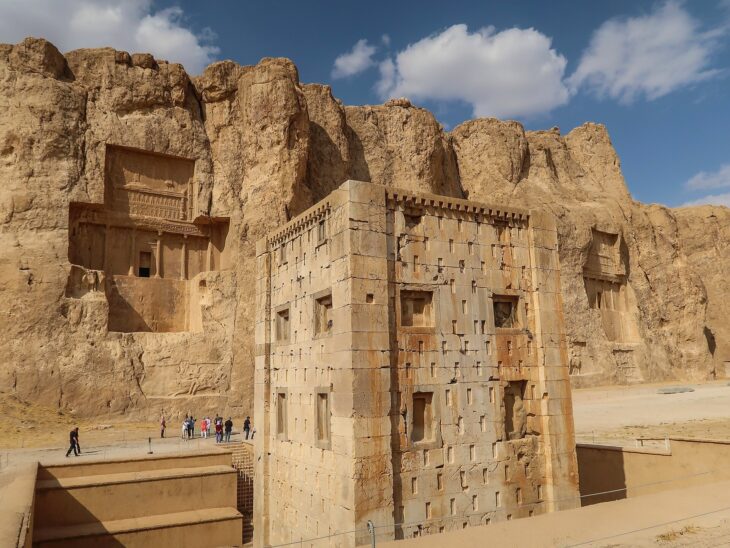

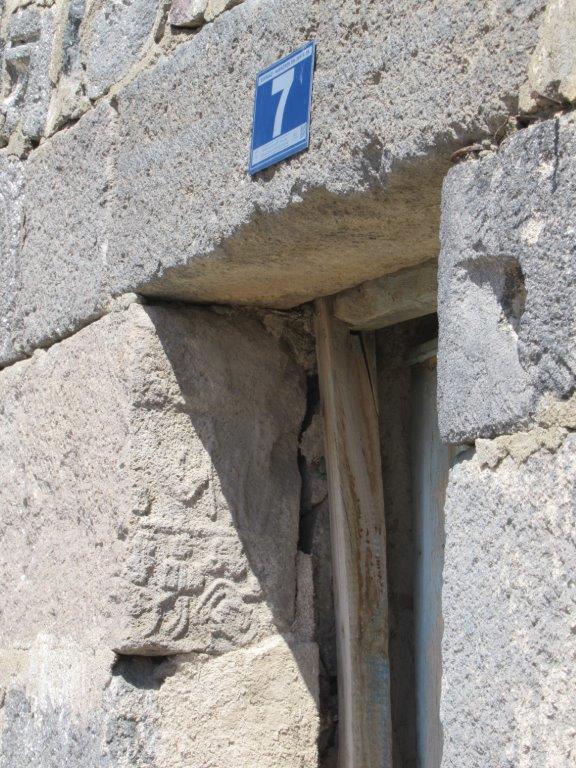

A Fortress Carved from Stone

Rabat Fortress itself is as dramatic as the text it preserved. Built atop a rocky ridge accessible only through narrow mountain valleys, the site features rock-cut tombs, stepped tunnels descending to water sources, fortification walls, and bridges. These features reveal a long-term elite investment in the landscape, transforming natural rock into a symbol of power and permanence.

Crucially, the inscription helps resolve a long-standing archaeological debate. Many of the rock-cut tunnels and tombs in eastern Anatolia were previously attributed to the Urartian period. The Rabat evidence now strongly supports a Hellenistic and later date, redefining how scholars interpret similar structures across the region.

Why This Discovery Matters

The Rabat Fortress inscription does more than add a new artifact to museum collections—it restores agency to local elites who have long been invisible in ancient history. It shows how regional rulers negotiated identity and power by invoking royal lineage, imperial memory, and sacred language, all while governing remote mountain territories.

As archaeological research continues in Tunceli and surrounding regions, scholars believe more discoveries may follow. For now, the voice carved into stone at Rabat Fortress stands as the first direct testimony of Sophene’s local elite, speaking across more than two millennia from a forgotten kingdom at the edge of empires.

Danışmaz H, Adalı S. F, Şahin Ö. New testimony for local elites in Sophene during the Hellenistic period: Rabat Fortress and its Middle Aramaic inscription in a rocky landscape. Anatolian Studies. 2025;75:165-186. doi:10.1017/S0066154625000109

Cover Image Credit: View of Rabat Fortress from the east (by H. Danışmaz, Ö. Şahin). Danışmaz H. (2025), Anatolian Studies