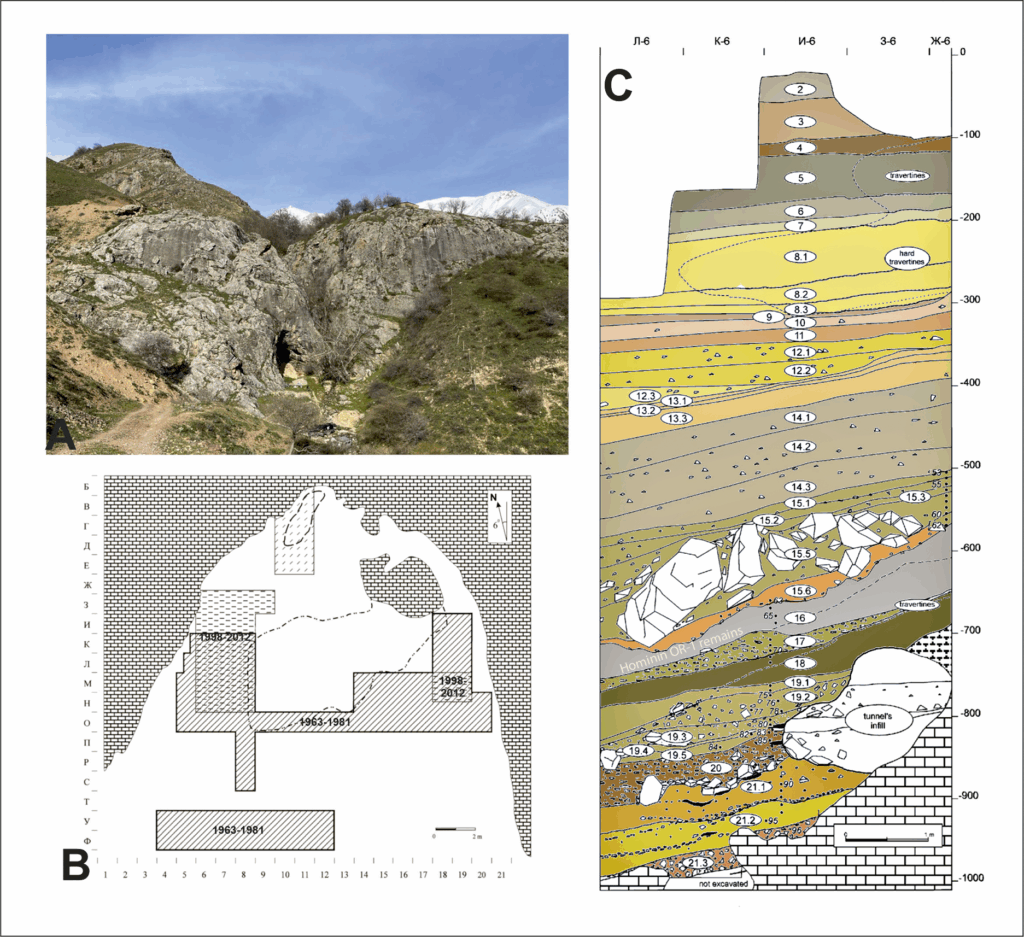

A remerkable discovery in the foothills of Central Asia may push the origins of bow-and-arrow technology back by thousands of years. Archaeologists working at the Obi-Rakhmat rock shelter in Uzbekistan have identified tiny stone points that appear to be arrowheads dating to nearly 80,000 years ago—making them the oldest known evidence of archery in human history.

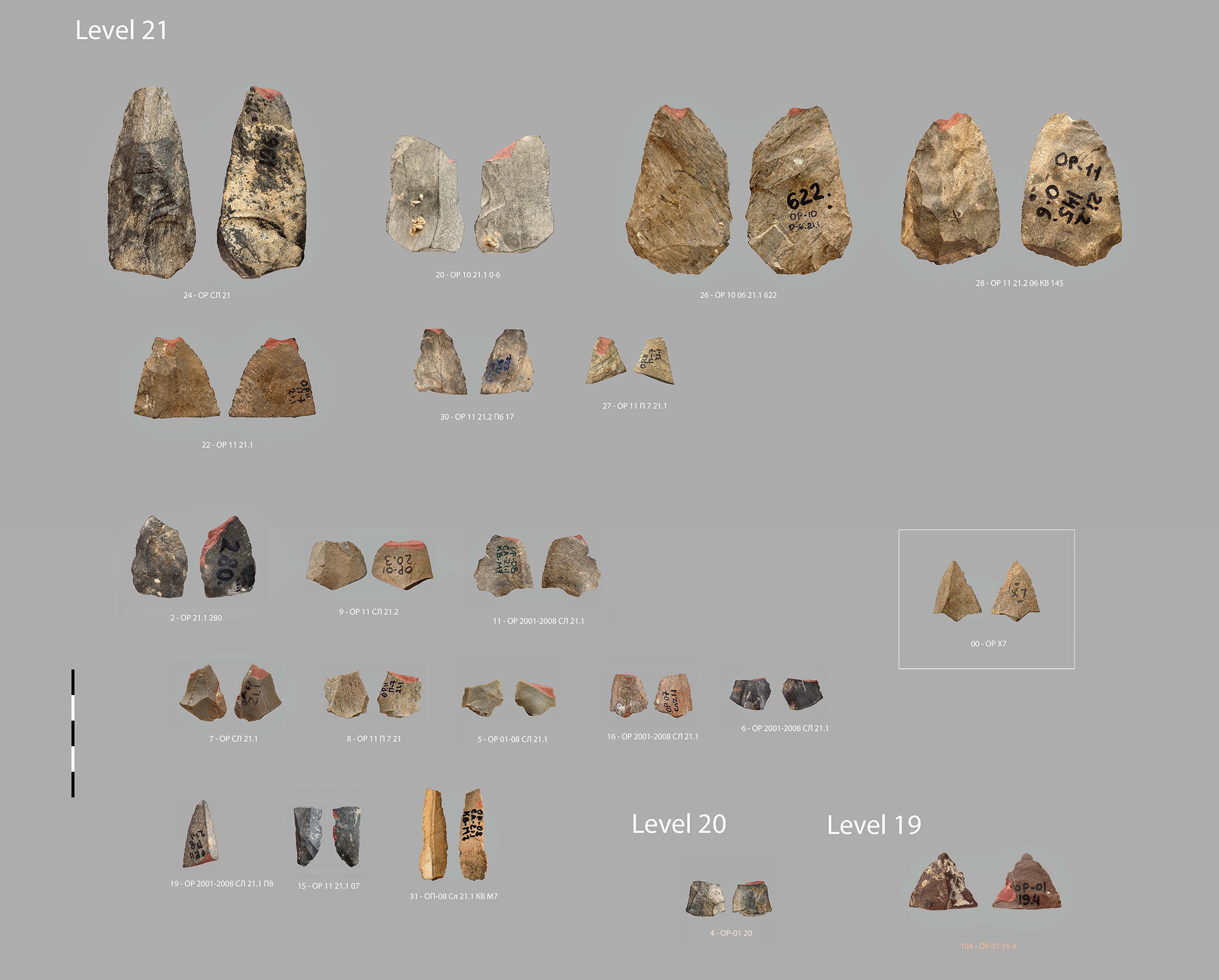

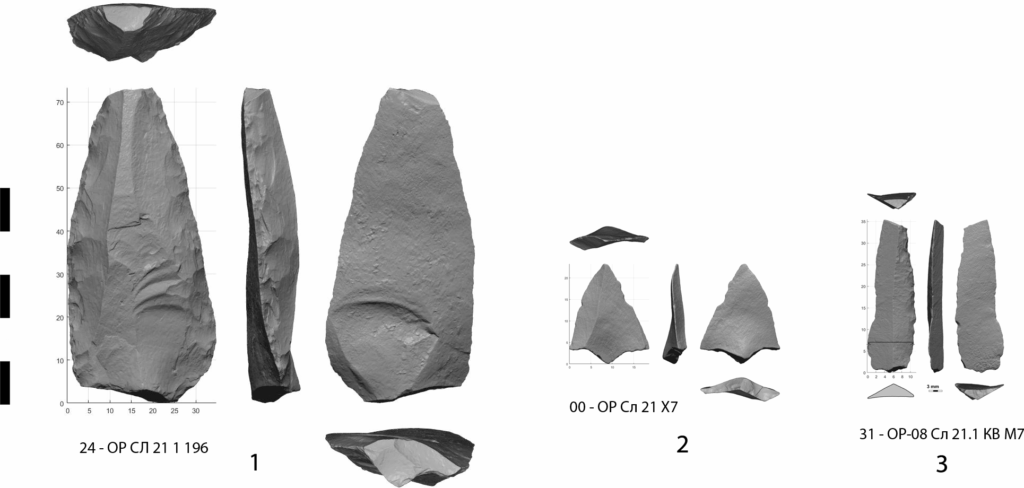

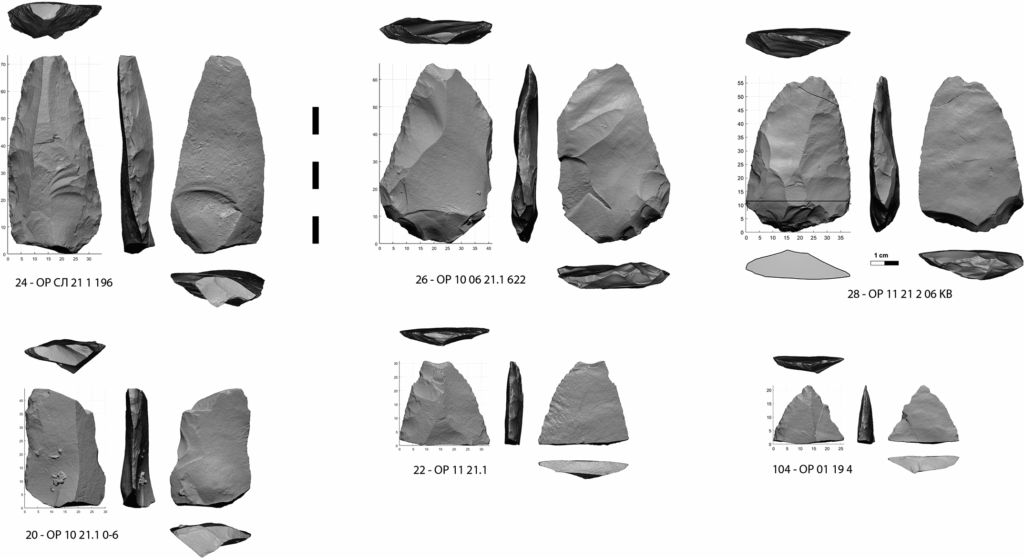

The findings, published in PLOS One in August 2025, describe over 190 “micropoints” found in the site’s deepest layers. Many of these miniature stone tips show fracture patterns and microscopic impact traces that strongly suggest they were used as projectiles launched from bows. If confirmed, the discovery would predate the earliest known African bow-and-arrow artifacts by at least 6,000 years, shifting the epicenter of this critical invention from Africa to Asia

Micropoints Too Small for Spears

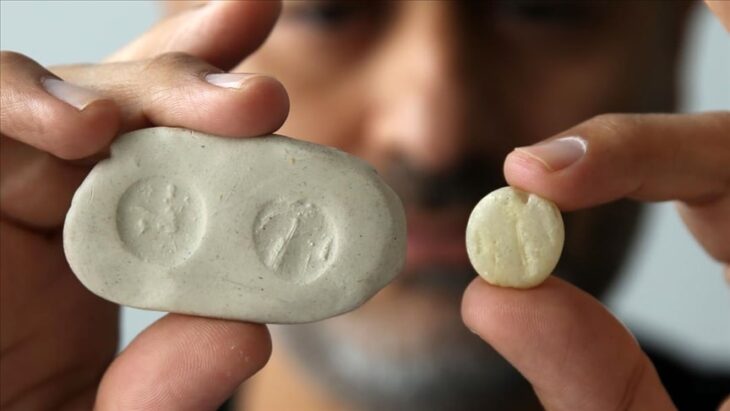

Unlike the larger spear points typically found at Neanderthal sites, the Obi-Rakhmat artifacts are remarkably small. Measuring just 15–24 millimeters and weighing between 1–2 grams, these arrowheads are far too delicate for spears or knives. Instead, their slim triangular shape and light weight align with the design principles of arrows.

“Such small points could not withstand the shock of being thrust as spears,” explains lead researcher Hugues Plisson of the University of Bordeaux. “Their dimensions only make sense when mounted on arrow shafts and propelled by a bow.”

The research team even recreated some of the micropoints using local stone, mounted them on wooden shafts with natural bitumen glue, and tested them with a modern bow. The breakage patterns matched those found on the ancient artifacts, strengthening the case for their use as arrowheads.

📣 Our WhatsApp channel is now LIVE! Stay up-to-date with the latest news and updates, just click here to follow us on WhatsApp and never miss a thing!!

Who Invented the Bow in Central Asia?

The discovery sparks a fascinating debate about who might have crafted these advanced weapons. Around 80,000 years ago, Central Asia was a crossroads where Neanderthals, early Homo sapiens, and possibly hybrid populations overlapped.

While Neanderthals are known for their hunting skills, no definitive Neanderthal arrowheads have ever been recorded. By contrast, early Homo sapiens are consistently associated with innovative projectile technologies. This raises the tantalizing possibility that the Obi-Rakhmat finds reflect one of the earliest expansions of modern humans into Eurasia—long before their better-documented dispersals around 60,000–50,000 years ago.

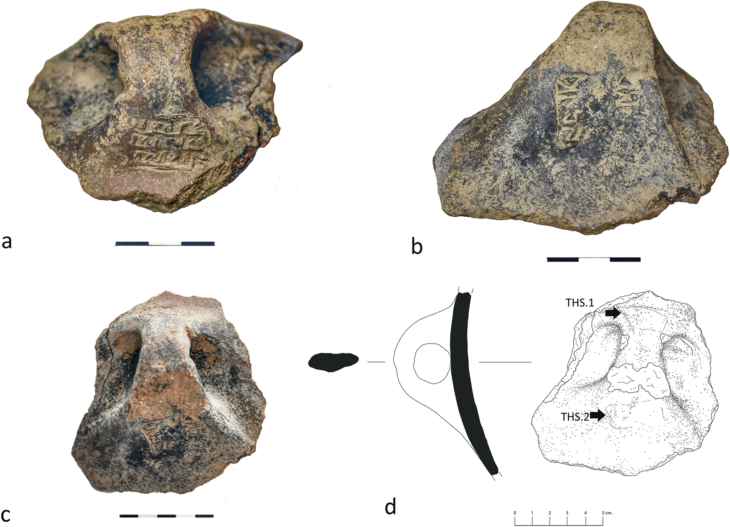

Adding to the intrigue, human remains discovered at Obi-Rakhmat in 2003 belonged to a juvenile whose teeth resembled Neanderthal traits, but whose skull showed ambiguous features, leaving open the possibility of a Neanderthal-Sapiens hybrid

Rewriting the Story of Hunting Technology

Until now, the earliest accepted bow-and-arrow evidence came from Ethiopia’s Pinnacle Point, dated to about 74,000 years ago. The Uzbekistan discovery, if authenticated, means that the invention of the bow was not an Africa-only development, but rather a more widespread and convergent innovation.

Comparisons with other sites deepen the mystery. Nearly identical micropoints were unearthed at Mandrin Cave in France, dated to 54,000 years ago and associated with early Homo sapiens. The striking similarity raises the possibility that small arrow technology spread across Eurasia through early human migrations, much earlier than previously thought.

“This pushes back the timeline for complex weapon systems and forces us to reconsider how knowledge and innovation were exchanged between populations,” says Plisson.

Why It Matters

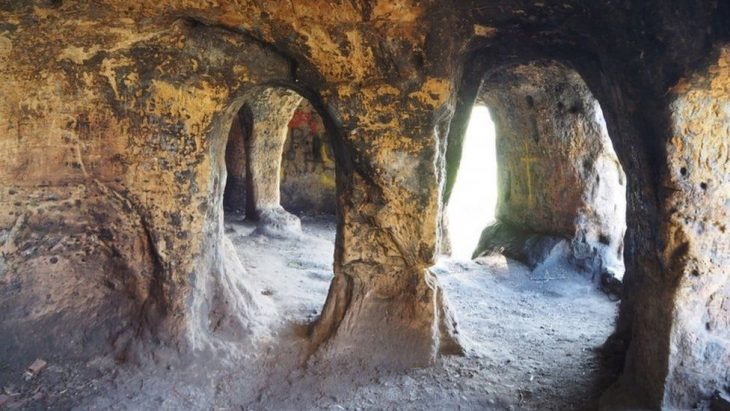

The bow-and-arrow was a transformative technology, allowing hunters to kill prey from a distance, expand their diets, and survive in challenging environments. In the rugged Tien Shan Mountains, where Obi-Rakhmat is located, such weapons would have been particularly useful for hunting elusive animals like wild goats and deer.

The new findings also add weight to the theory that Central Asia served as a key population hub for early humans after their migration out of Africa. Archaeologists now suspect that this region was not just a corridor of movement but also a center of technological innovation.

What Comes Next?

Researchers are continuing excavations at Obi-Rakhmat, aiming to confirm whether the micropoints appear in higher layers and whether similar tools emerge at other sites in the region. They also hope to recover genetic material from the site’s human remains to resolve the mystery of whether Neanderthals, Homo sapiens, or hybrids were the true inventors of the bow in Central Asia.

For now, the discovery of 80,000-year-old arrowheads at Obi-Rakhmat stands as one of the most significant archaeological finds of the decade. If verified, it means humanity’s relationship with bows and arrows—an invention that shaped hunting, warfare, and survival for millennia—began much earlier, and in more places, than anyone had imagined.

Plisson, H., Kharevich, A. V., Kharevich, V. M., Chistiakov, P. V., Zotkina, L. V., Baumann, M., Pubert, E., Kolobova, K. A., Maksudov, F. A., & Krivoshapkin, A. I. (2025). Arrow heads at Obi-Rakhmat (Uzbekistan) 80 ka ago? PLOS ONE, 20(8), e0328390. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0328390

Cover Image Credit: Obi-Rakhmat: Impacted points and bladelets. The unbroken Levallois point in the white frame (00 – OP X7) illustrates what the ideal type of micropoint was likely to be. H. Plisson et al., PLOS ONE