The Indus River Valley (or Harappan) civilization (3300-1300 BCE) lasted 2,000 years and spanned northeast Afghanistan to Pakistan and northwest India. Remains of this vast civilization of South Asia are scattered over an area considerably larger than those covered by either ancient Egypt or Mesopotamia.

However, little was known about this ancient culture until the 1920s, when modern archaeologists excavated two long-buried cities. These two cities were the cities of Harappa and Mohenjo-Daro.

Prior to the discovery of these Harappan cities, scholars believed that Indian civilization began in the Ganges valley around 1250 BCE, when Aryan immigrants from Persia and Central Asia settled there. The discovery of ancient Harappan cities shifted the timeline back another 1500 years, placing the Indus Valley Civilization in an entirely different environmental context.

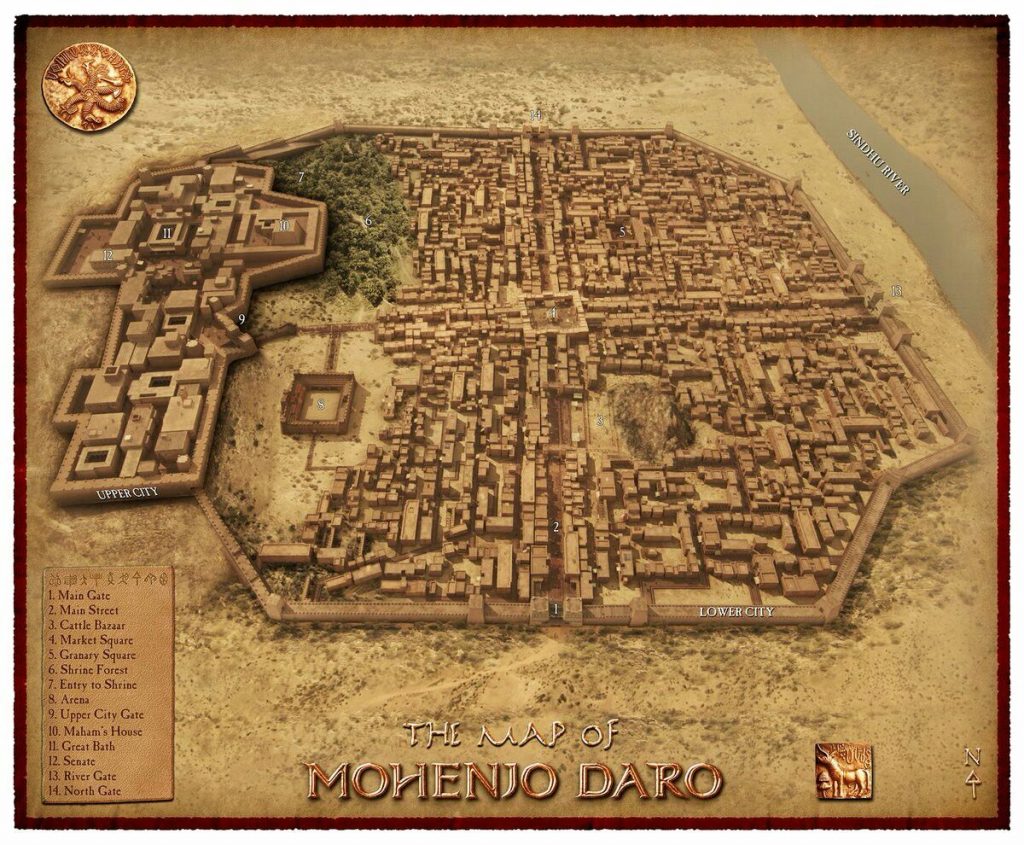

Mohenjo-Daro is thought to have been built in the 26th century BCE; it was not only the largest city of the Indus Valley Civilization but also one of the world’s earliest major urban centers. Mohenjo-Daro, located west of the Indus River in the Larkana District, was one of the most advanced cities of the time, with advanced engineering and urban planning.

By 2600 BCE, small Early Harappan communities had developed into large urban centers. These cities include Harappa, Ganeriwala, and Mohenjo-Daro in modern-day Pakistan and Dholavira, Kalibangan, Rakhigarhi, Rupar, and Lothal in modern-day India. In total, more than 1,052 cities and settlements have been found, mainly in the general region of the Indus River and its tributaries.

📣 Our WhatsApp channel is now LIVE! Stay up-to-date with the latest news and updates, just click here to follow us on WhatsApp and never miss a thing!!

The name Mohenjo-Daro means ‘Mound of the Dead Men’. Mohenjo-Daro, which covered 300 hectares (about 750 acres) and had a peak population of about 40,000 people, was one of the world’s largest and most advanced cities at the time. The city, laid out in a rectilinear grid and built of baked bricks, featured a complex water management system, including sophisticated drainage and covered sewer system, as well as baths in nearly every house. The original name of the city is forgotten, although one scholar speculates it may have been Kukkutarma, or “The City of the Cockerel” (a.k.a., Rooster City).

The fact that the manufactured bricks used to construct Mohenjo-Daro were all the same size, that standardized weights and measurements were found to be used to facilitate trade, that the city’s development showed a high level of civil engineering and urban planning, and that these traits are shared with other Indus-Sarasvati Valley sites, especially Harappa, the first site to be excavated, all point to a highly organized civilization with bureaucratic coordination of things like.

The ancient Indus sewage and drainage systems developed and used in cities throughout the Indus region were far more advanced than those found in contemporary urban sites in the Middle East, and even more efficient than those found in many areas of Pakistan and India today. Individual homes drew water from wells, while wastewater was directed to covered drains on major thoroughfares. Houses opened only to inner courtyards and smaller lanes, and even the smallest homes on the city outskirts were believed to have been connected to the system, further supporting the conclusion that cleanliness was a matter of great importance.

Given that, it may seem puzzling to observe that Mohenjo-Daro lacks any palaces, temples, monuments, or anything else resembling a seat of governmental authority. The largest buildings in the city are things like assembly halls, public baths (one of which had an underground furnace to heat the pools), a marketplace, old apartment buildings, and the aforementioned sewer system; all of these indicate an emphasis on a tidy, modest, and orderly civil society.

Unlike the Egyptian and Mesopotamian civilizations, the Indus Valley Civilization appears to have lacked temples or palaces that would have provided clear evidence of religious rites or specific deities.

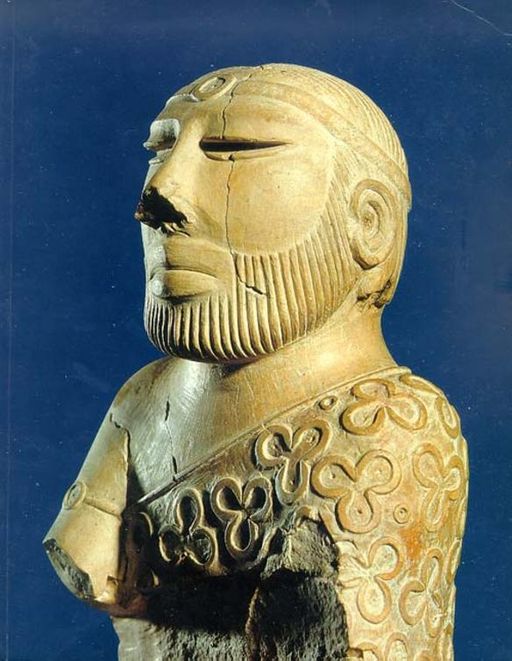

The Indus Priest/King Statue found at Mohenjo-Daro in 1927 is quite interesting. The statue is 17.5 cm high and carved from steatite. Among the various gold, terracotta, and stone figurines found was a figure of a priest-king displaying a beard and patterned robe. Another bronze figurine, the Dancing Girl, stands just 11 centimeters tall and depicts a female figure in a pose that suggests the existence of some choreographed dance form that the civilization’s members enjoyed. There were also terracotta works of cows, bears, monkeys, and dogs. The inhabitants of the Indus River Valley are thought to have also produced necklaces, bangles, and other ornaments in addition to figurines.

Written records provided historians with a wealth of information about ancient Mesopotamia and Egypt, but very few written materials have been discovered in the Indus Valley. Though seal inscriptions appear to contain written information, scholars have yet to decipher the Indus script. As a result, they have had significant difficulty comprehending the nature of the Indus Valley Civilization’s state and religious institutions. We know very little about their legal codes, procedures, and governance systems.

Mohenjo Daro has also been associated with an atomic blast. During the research, 44 skeletons were found. Certain zones of the site additionally indicated expanded dimensions of radioactivity.

David Davenport, an English-Indian analyst, noticed evidence of what appeared to be the impact epicenter: a 50-yard sweep at the site revealed that all objects had been intertwined and glassified, meaning that rocks had been dissolved at temperatures of around 1500 degrees and changed into a material that resembled glass.

Davenport additionally clarified that what was found at Mohenjo-Daro emulates precisely the impacts of the fallout that occurred in Hiroshima and Nagasaki amid the twentieth century.

According to A. Gorbovsky’s book “Conundrums of Ancient History,” at least one skeleton discovered at the site contained more radiation than it should have, and numerous “dark stones,” which were once mud vessels, were discovered together due to unusual warmth.

All things considered, numerous researchers have disproved these findings with evidence suggesting that the bodies discovered at Mohenjo-Daro were all part of the sloppiest, most despicable kind of mass grave. Some people have observed that the simple mud-block structures should have been completely destroyed by an atomic explosion, despite the fact that some of those structures were still standing at a height of 15 feet.

However, there is unquestionably enough evidence for us to consider the possibility that our understanding of human history is incomplete. What might be the origin of this radioactivity? Could there have been atomic-abilities people a very long time ago? The questions can be increased.

Just what ended the Indus civilization—and Mohenjo Daro—is also a mystery. Mohenjo-Daro went into sudden decline for unknown reasons in 1900 BCE and was subsequently abandoned possibly because of the drying up of a major Sarawati River.

Following its rediscovery in the 1920s, several decades of excavations exposed the historic buildings to significant weather damage. As a result, all further archaeological work on the site was stopped in 1966; today, only salvage excavations, surface surveys, and conservation projects are permitted. However, the city is under threat from the recent heavy monsoon rains.

Cover Photo: Wikipedia