Recent archaeological discoveries in Oman are reshaping long-held assumptions about how early human communities adapted to harsh environments. An international research team led by the Archaeological Institute of the Czech Academy of Sciences has uncovered compelling evidence that Neolithic populations living in southern Arabia around 7,000 years ago systematically hunted and consumed sharks as a central component of their diet.

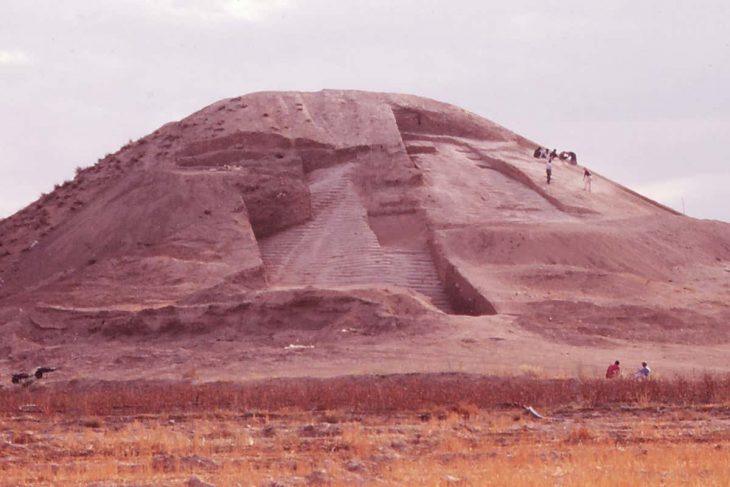

The findings come from Wadi Nafūn, an arid inland valley in present-day Oman, where researchers identified the oldest known collective Neolithic megalithic tomb in southern Arabia. Far more than a burial site, the monument has emerged as a key source of information about subsistence strategies, mobility patterns, ritual behavior, and environmental adaptation during the first half of the fifth millennium BCE.

The Oldest Collective Neolithic Megalithic Tomb in Southern Arabia

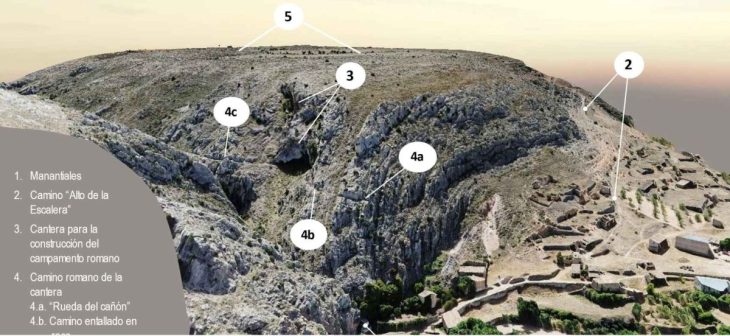

Excavations at Wadi Nafūn, ongoing since 2020, revealed a monumental funerary complex consisting of circular stone burial mounds constructed from locally sourced limestone and dolomite slabs. One fully excavated mound contained the commingled remains of more than 70 individuals of all ages and sexes, deposited over a period exceeding 300 years.

Radiocarbon dating, corrected for a significant marine reservoir effect, places the use of the site firmly in the early Neolithic period. The collective nature of the burials, combined with the scale of construction, indicates a high degree of social organization and long-term cultural continuity among communities spread across a wide geographic area.

According to project director Dr. Alžběta Danielisová, the site functioned as a central ritual place that unified multiple Neolithic groups across southern Arabia. “This monument was not built by a single small group,” she explains. “It represents cooperation, shared beliefs, and repeated return to a common ceremonial landscape.”

📣 Our WhatsApp channel is now LIVE! Stay up-to-date with the latest news and updates, just click here to follow us on WhatsApp and never miss a thing!!

Reconstructing Diet in an Extreme Desert Environment

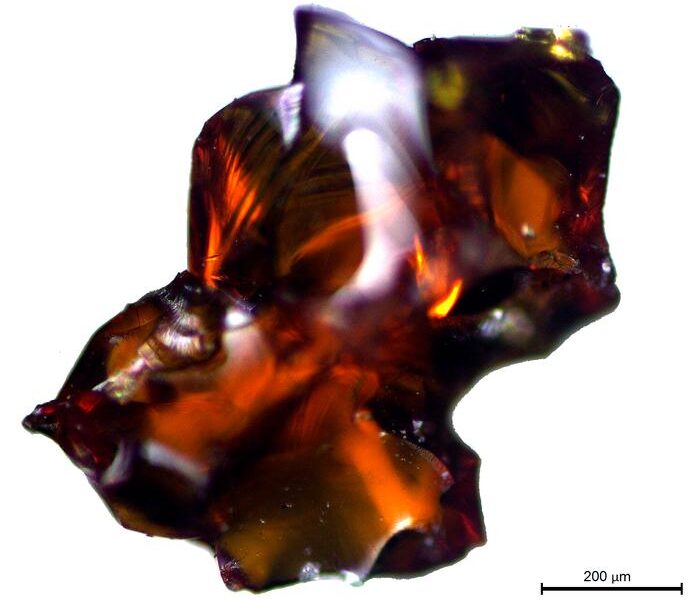

Oman’s arid climate poses major challenges for archaeological research. Organic materials such as collagen rarely survive, rendering many conventional biochemical analyses impossible. To overcome this limitation, the research team focused on the mineral component of bones and teeth—bioapatite—which remains stable even in extreme desert conditions.

Dental and skeletal samples were transported to specialized laboratories in the Czech Republic and Germany, including the Max Planck Institute for Chemistry in Mainz. Using advanced stable isotope analysis of carbon, oxygen, strontium, and nitrogen, scientists reconstructed both diet and mobility patterns with unprecedented precision.

The results were striking. Isotopic signatures revealed an unusually high contribution of marine resources to the diet, despite the site’s inland location. Most notably, elevated nitrogen isotope values pointed to the consumption of protein from the very top of the marine food chain.

Evidence for Specialized Shark Hunting

Based on isotopic data, researchers propose that shark meat was not an occasional food source but a staple of the Neolithic diet in this region. “We are not talking about generic marine protein,” says anthropologist Dr. Jiří Šneberger, a member of the research team. “These values suggest regular consumption of apex predators, most plausibly sharks.”

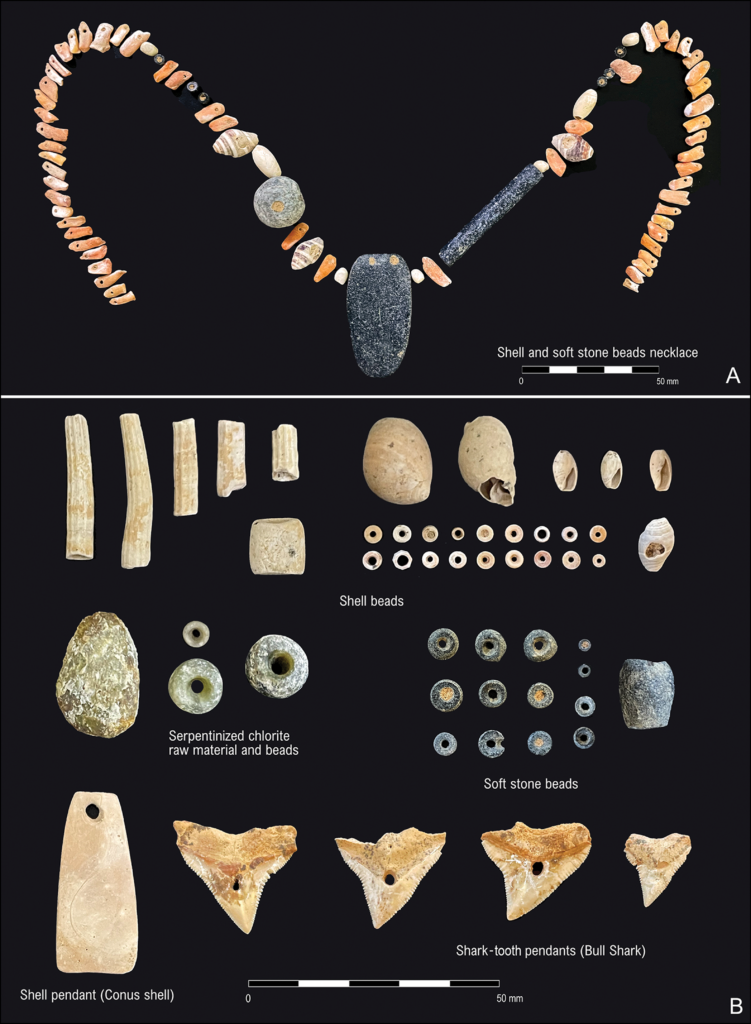

This interpretation is supported by archaeological finds from the burial complex itself, including shark-tooth pendants, tiger shark teeth, stingray barbs, and fishing-related artifacts. Together, these objects suggest both symbolic and practical relationships between the community and large marine animals.

If confirmed, this would represent the earliest direct evidence of systematic shark hunting by human populations anywhere in the arid belt of the Old World.

Teeth as Tools and Traces of Daily Life

Microscopic analysis of dental wear provided additional insights into daily practices. The teeth of individuals buried at Wadi Nafūn show distinctive wear patterns that reflect not only diet but also the use of teeth as tools—possibly for processing animal hides, fibers, or fishing equipment.

Further confirmation of dietary habits is expected from ongoing research into dental calculus. Ancient tartar can preserve microscopic food particles and proteins, offering direct biomolecular evidence of consumed species, potentially including shark tissue.

Mobility, Trade, and Regional Connectivity

Strontium and oxygen isotope analyses revealed that the burial population was not homogeneous. Some individuals spent their childhoods up to 50 kilometers away from Wadi Nafūn, indicating high mobility and regular movement between inland and coastal zones.

This mobility likely played a crucial role in accessing marine resources. It suggests that Neolithic communities maintained seasonal routes or exchange networkslinking desert interiors with the Arabian Sea coast, allowing them to exploit diverse ecological niches efficiently.

Redefining Neolithic Life in Arabia

Traditionally, Neolithic societies in arid regions have been portrayed as marginal, resource-limited, and highly vulnerable to environmental stress. The evidence from Wadi Nafūn challenges this narrative.

Instead, it reveals communities that were remarkably adaptive, combining hunting, gathering, pastoralism, and intensive marine exploitation into a flexible and resilient subsistence strategy. Their ability to hunt large marine predators demonstrates advanced ecological knowledge, technological skill, and social coordination.

Published in the peer-reviewed journal Antiquity, the study highlights how human innovation and adaptability allowed Neolithic populations to thrive in environments previously considered inhospitable.

A Site of Global Archaeological Significance

Wadi Nafūn now stands as a landmark site for understanding human-environment interaction in prehistory. Its combination of monumental architecture, long-term ritual use, and cutting-edge bioarchaeological data provides rare insight into how early societies responded to climatic fluctuation and ecological opportunity.

As research continues, including proteomic and microfossil analyses, the site promises to yield even deeper understanding of Neolithic life at the crossroads of desert and sea—where, 7,000 years ago, humans learned not just to survive, but to master their environment, even at the top of the ocean’s food chain.

Danielisová A, Maiorano MP, Šneberger J, et al. The first collective Neolithic megalithic tomb in Oman. Antiquity. 2025;99(408):e54. doi:10.15184/aqy.2025.10146

Archaeological Institute of the Czech Academy of Sciences (Archeologický Ústav AV ČR)

Cover Image Credit: Archaeological Institute of the Czech Academy of Sciences (Archeologický Ústav AV ČR)