Archaeologists representing Spain’s National Research Council (CSIS) excavating at the site of Casas del Turunuelo have uncovered the first human representations of the ancient Tartessos people.

The incredible results of an excavation that shed light on a mysterious and ancient civilization that flourished in southern Spain several centuries before Christ have been presented by Spain’s National Research Council.

The Tartessians, who are thought to have lived in southern Iberia (modern-day Andalusia and Extremadura), are regarded as one of the earliest Western European civilizations, and possibly the first to thrive in the Iberian Peninsula.

In the southwest of Spain’s Iberian Peninsula, the Tartessos culture first appeared in the Late Bronze Age. The culture is distinguished by a blend of local Paleo-Hispanic and Phoenician traits, as well as the use of a now-extinct language known as Tartessian. The Tartessos people were skilled in metallurgy and metal working, creating ornate objects and decorative items.

Archaeologists from Spain’s National Research Council (CSIS) on Tuesday presented the amazing results of excavation at the Casas de Turuuelo dig in Badajoz, in southwest Spain, as well as the results of the excavation.

📣 Our WhatsApp channel is now LIVE! Stay up-to-date with the latest news and updates, just click here to follow us on WhatsApp and never miss a thing!!

Five busts, damaged but two of which maintain a great degree of detail, are the first human and facial representations of the Tartessian people that the modern world has ever seen.

These “extraordinary findings” represent a “profound paradigm shift” in the interpretation of Tartessian culture, excavation leaders Celestino Pérez and Esther Rodríguez said during the press conference.

Given the scarcity of Tartessian archaeological finds thus far, this ancient society is shrouded in mystery.

Tartessos’ port was located at the mouth of the Guadalquivir river in what is now Cádiz, according to historical records. In the fourth century BC, Greek historian Ephorus described it as a prosperous civilization centered on the production and trade of tin, gold, and other metals.

What is unknown is where the Tartessians came from, whether they were an indigenous tribe with Eastern influences or a Phoenician colony that settled beyond the Pillars of Hercules (the Strait of Gibraltar).

The team from Mérida’s Institute of Archaeology believes two of the busts discovered in what is thought to be a shrine or pantheon represent Tartessian goddesses, despite the fact that Tartessian religion was previously thought to be aniconic (opposed to the use of idols or images).

The stone busts’ facial depiction, as well as the inclusion of jewelry (hoop earrings) and their specific hairstyles, resemble ancient sculptures from the Middle East and Asia.

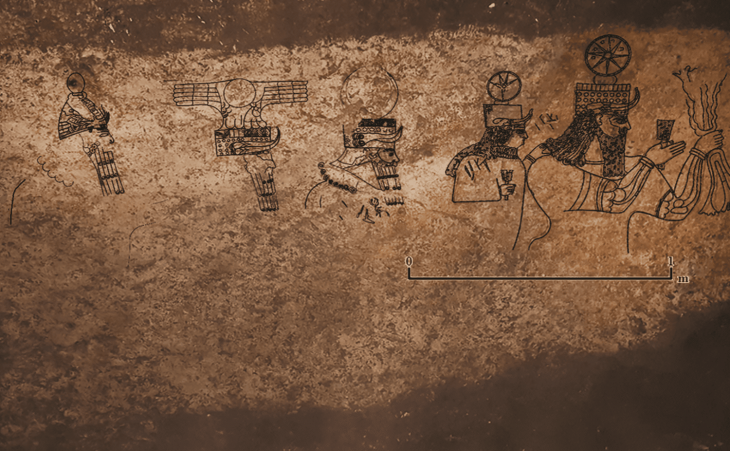

Archaeologists believe that the two goddesses, along with three other sculptures that were significantly more damaged, were part of a stone mural depicting four deities watching over a Tartessian warrior, as one of the defaced busts has a helmet.

The ornate effigies, which are thought to be around 2,500 years old, are also significant for art historians, as Ancient Greece and Etruria (an ancient civilization in modern-day central Italy) was previously recognized as the epicenters of sculpting during this time period.