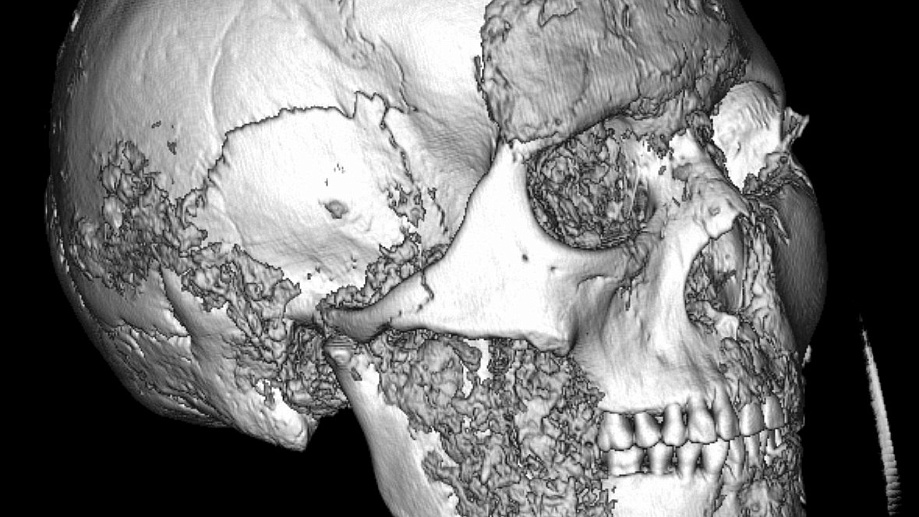

Researchers from Novosibirsk State University (NSU) have uncovered compelling evidence of a highly sophisticated surgical procedure performed approximately 2,500 years ago on a woman of the Pazyryk culture. Using advanced computed tomography (CT) imaging, scientists identified traces of a complex jaw reconstruction surgery that challenges current understanding of ancient medicine in the Siberian Iron Age.

The discovery was made during a detailed study of a skull recovered from the Upper Kaljin-2 burial ground on the Ukok Plateau in the Altai Republic. The burial site belongs to the Pazyryk culture, a Scythian-era civilization known for its remarkably preserved “frozen” tombs dating from the 6th to 3rd centuries BCE.

CT Technology Unlocks Secrets of the Past

The examination was conducted at NSU’s Laboratory of Nuclear and Innovative Medicine using a Philips MX 16 CT scanner. The technology allowed researchers to digitally remove preserved soft tissue that had previously obscured the skull’s bone structures.

According to Vladimir Kanygin, head of the laboratory, CT imaging acted as a “time machine,” enabling non-destructive access to anatomical details hidden for millennia. The scan produced 551 ultra-thin slices (0.75 mm thickness), generating a precise 3D reconstruction of the skull for comprehensive anthropological and medical analysis.

The results were extraordinary.

📣 Our WhatsApp channel is now LIVE! Stay up-to-date with the latest news and updates, just click here to follow us on WhatsApp and never miss a thing!!

Evidence of Severe Trauma and Advanced Surgical Intervention

The CT images revealed that the woman had suffered a significant head injury during her lifetime. The right temporal bone showed a depression fracture of approximately 6–8 millimeters. Most critically, the trauma destroyed her right temporomandibular joint (TMJ), displacing the jaw and rupturing ligaments.

Such an injury would have left her unable to chew or speak properly. Without medical intervention, survival would have been unlikely.

However, researchers discovered unmistakable evidence of surgery.

Two narrow, precisely drilled bone channels—each about 1.5 mm in diameter—were found intersecting at a right angle in the joint area. One channel passed through the head of the lower jaw, and the other through the zygomatic process of the temporal bone. Around these holes, ring-shaped bone growth indicated healing, proving the procedure was performed while the woman was alive.

Even more remarkably, traces of elastic organic material—possibly horsehair or animal tendon—were found within the channels. This material likely functioned as a primitive surgical ligature, stabilizing the joint and effectively acting as an early form of prosthetic fixation.

The surgical precision was striking. The drilling was smooth and controlled, and the bone remodeling showed that the patient survived long enough for significant healing to occur.

Long-Term Survival Confirmed by Dental Evidence

Additional confirmation of her survival came from dental asymmetry. The left side of her jaw exhibited severe wear, chipped molars, and inflammatory changes around the roots—clear signs of prolonged overuse. Meanwhile, the injured right side showed comparatively better preservation.

This pattern suggests that although the reconstructed joint functioned, chewing on the injured side likely remained painful. The woman adapted by shifting most of the load to the left side for an extended period—possibly months or even years.

Experts estimate that she was between 25 and 30 years old at the time of death, which represented a mature age in her era.

Burial Context: Upper Kaljin-2 and the Ukok Plateau

The Upper Kaljin-2 burial ground was discovered in 1994 by archaeologist Vyacheslav Molodin on the remote Ukok Plateau. The site includes several small kurgans (burial mounds), two of which were undisturbed and yielded exceptionally preserved artifacts.

The woman’s burial was unusual. Unlike other Pazyryk graves filled with grave goods, her tomb contained no significant objects except a traditional wig typical of Pazyryk women. The burial chamber was constructed from massive larch logs—an impressive architectural effort in the largely treeless high-altitude plateau.

Natalia Polosmak emphasized that the burial itself raises important cultural questions. On the largely treeless Ukok Plateau, transporting massive larch logs for the burial chamber would have been costly and labor-intensive. At the same time, the absence of grave goods remains unusual and unexplained.

“The surgery itself shows that her life was valued,” Polosmak noted. “We do not know what made her personally important to her community. Every Pazyryk individual likely possessed essential — sometimes unique — skills: woodworking, sewing, felt appliqué, tattooing, healing, storytelling, and many others we may never fully understand. In this society, people were valued simply because they existed, and they were honored after death.”

Her partially mummified head was preserved and later transferred to the Institute of Archaeology and Ethnography of the Siberian Branch of the Russian Academy of Sciences for further study.

A Culture of Surgical Knowledge

This discovery does not stand entirely alone. Previous research on another famous Ukok mummy—often referred to as the “Ukok Princess”—demonstrated evidence of cranial trepanation. That mummy is associated with the Ak-Alakha-3 burial site.

The Pazyryk people practiced mummification, which required anatomical knowledge of internal organs and body structures. Researchers believe that this tradition may have contributed to the development of surgical skills.

In fact, parallels are often drawn with ancient Egypt. Classical historian Herodotus described how Egyptian embalmers and surgeons developed advanced techniques due to their familiarity with the human body through mummification practices.

The Pazyryk case suggests a similar trajectory of medical knowledge development in the Siberian Iron Age.

Survival in Harsh Mountain Conditions

Life on the Ukok Plateau was harsh and physically demanding. The Pazyryk population was relatively small, with low birth rates and short life expectancy—particularly among women. In such conditions, preserving each life would have been crucial for community survival.

Researchers emphasize that surgery is one of the most essential branches of medicine for sustaining life. The ability to treat traumatic injuries—possibly from horse riding accidents or falls—would have been vital in a mobile, equestrian society.

The fine craftsmanship observed in Pazyryk leather garments and wooden artifacts also demonstrates highly developed manual dexterity. Some leather coats from the region were stitched with tendon threads spaced just 4 millimeters apart, with up to 20 stitches per centimeter—precision that parallels surgical skill.

A Landmark Discovery in Ancient Medical History

Radiologist Andrey Letyagin, who led the medical imaging analysis, noted that the CT scanner was operated at maximum settings—levels rarely used in clinical practice due to radiation exposure. Because the subject was an archaeological artifact, researchers were able to obtain exceptionally high-resolution images.

The findings represent what may be the first documented case in scientific literature of temporomandibular joint reconstruction performed in deep antiquity.

While the exact circumstances of the original injury remain unknown, researchers speculate it could have resulted from a fall from a horse or from height. What is clear is that her community did not abandon her after severe trauma. Instead, they performed a technically complex operation that restored essential functions—speech and eating—and extended her life.

This discovery significantly reshapes our understanding of ancient Siberian medicine. Far from being primitive, the Pazyryk people demonstrated surgical innovation, anatomical knowledge, and technical skill that rivaled other advanced ancient civilizations.

As CT technology continues to be applied to archaeological materials, more hidden chapters of early medical history may soon emerge from beneath the frozen soils of the Altai Mountains.

Novosibirsk State University (NSU)

Cover Image Credit: Reconstruction of a Pazyryk woman from 2,500 years ago, based on archaeological evidence. AI-generated by the author.