Music is a form of art, which derives from the Greek word meaning “art of the Muses.”

While it is not certain how or when the first musical instrument was invented, most historians point to early flutes made from animal bones that are at least 40,000 years old. The oldest known written song dates back 4,000 years and was written in ancient cuneiform.

Instruments were created to make musical sounds. Any object that produces sound can be considered a musical instrument if it is specifically designed for that purpose. But what about complex musical instruments?

Archaeological records of Elam, the oldest civilization in the southwestern Iranian plateau, suggest the ancient land is the birthplace of the earliest complex instruments, which date back to the third millennium BC.

Narratives say the initiation of music in Iran dates back to the time of the mythical king, Jamshid. However, fragmentary documents from various periods, including rock-carved carvings, suggest millennia of musical practices in every corner of the ancient land.

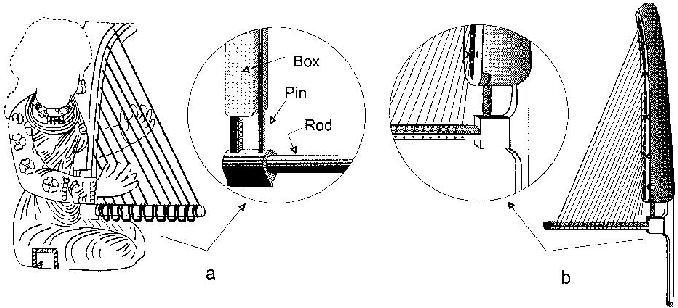

Archeologists have discovered many trumpets made of silver, gold, and copper were found in eastern Iran attributed to the Oxus civilization and date back between 2200 and 1750 BC. The use of both vertical and horizontal angular harps has been documented at the archaeological sites of Madaktu (650 BC) and Kul-e Fara (900–600 BC), with the largest collection of Elamite instruments documented at Kul-e Fara. Multiple depictions of horizontal harps were also sculpted in Assyrian palaces, dating back between 865 and 650 BC.

Not much is known of the musical scene of the classical Persian empires of the Medes, Achaemenids, and Parthians, apart from a few archaeological remains and some notes from the writings of Greek historians.

Xenophon’s Cyropaedia also speaks of many singing women at the court of the Achaemenid Empire.

The Sassanian period (226 CE-651), in particular, has left us ample evidence pointing to the existence of a lively musical life. Sassanid ruler Khosrau’s II reign is considered the “golden age” for Iranian music.

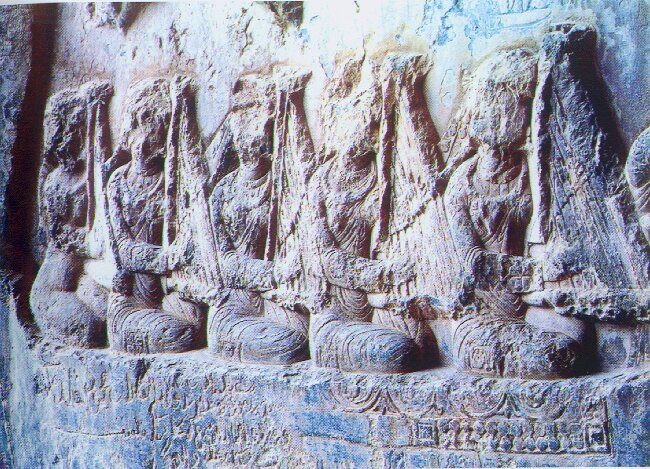

In a large relief at the Taq-e Bostan archaeological site, he is shown among his musicians, holding a bow and arrow and standing on a boat in the middle of a group of harpists. The names of some important musicians such as Barbod, Parkash, Azad, Nakissa, and Ramtin, and titles of some of their works have survived.

With the advent of Islam in the 7th century CE, Persian music, as well as other Persian cultural taints, became the main formative element in what has, ever since, been known as “Islamic civilization”.

According to Encyclopedia Iranica, Persian musicians and musicologists overwhelmingly dominated the musical life of the Muslim lands. Farabi (d. 950), Ebne Sina (d. 1037), Razi (d. 1209), Ormavi (d. 1294), Shirazi (d. 1310), and Maraqi (d. 1432) are but a few among the array of outstanding Persian musical scholars in the early Islamic period.

In the 16th century, a new “golden age” of Persian civilization dawned under the rule of the Safavid dynasty (1499-1746). However, from that time until the third decade of the 20th-century Persian music became gradually relegated to a mere decorative and interpretive art, where neither creative growth nor scholarly research found much room to flourish.

When it comes to structure, perpetuated through an oral tradition, the classical repertoire encompasses a body of ancient pieces collectively known as the “radif” of Persian music. These pieces are organized into twelve groupings, seven of which are known as basic modal structures and are called the seven “dastgah” (systems).

They include : Shur, Homayun, Segah, Chahargah, Mahur, Rast-Panjgah, and Nava. The remaining five are commonly accepted as secondary or derivative dastgahs. Four of them: Abuata, Dashti, Bayat-e Tork, and Afshari are considered to be derivatives of Shur; and, Bayat-e Isfahan is regarded to be a sub-dastgah of Homayun. The individual pieces in each of the twelve groupings are generally called “gushe”, but each gushe has a specific and often descriptive title. A gushe is not a clearly defined musical composition; rather, it represents modal, melodic, and occasionally rhythmic skeletal formulae upon which the performer is expected to improvise. Thus, the radif submits an infinite source of musical expression. The flexibility of the basic material and the extent of the improvisatory freedom is such that a piece played twice by the same performer, at the same sitting, will be different in melodic composition, form, duration, and emotional impact.

For those with a passion for music, it is worthy to spend a few hours in one of the museums dedicated to the music of the nation. An example is the Isfahan Music Museum located in the Armenian quarter of Jolfa in Isfahan. It showcases 300 regional and national musical instruments.

Source: Tehran Times