A newly analyzed archaeological discovery in the United Arab Emirates sheds light on a bustling ancient crossroads where travelers moving between Mesopotamia, Iran, India, and South Arabia paused to pray, trade, and give thanks.

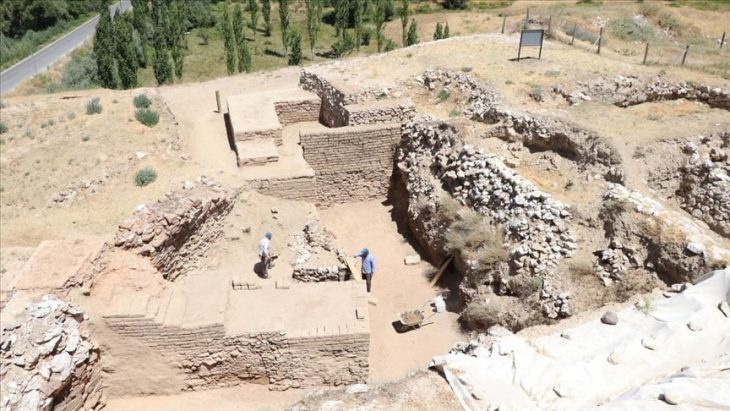

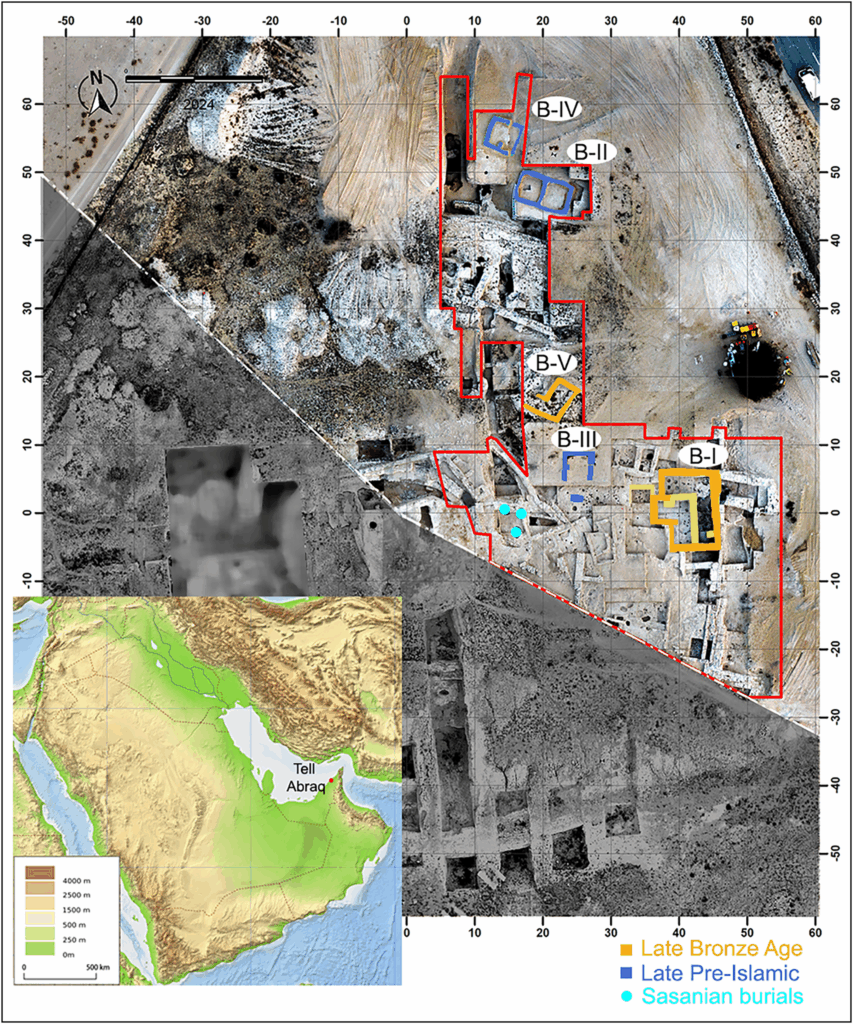

On the western coastline of the United Arab Emirates, the windswept mound of Tell Abraq has long been known as one of the Gulf’s most important archaeological sites. But recent excavations and a new analysis by the Italian Archaeological Mission in Umm al-Quwain (IAMUQ) have dramatically expanded our understanding of this ancient settlement—revealing that it functioned as both a strategic trading hub and, at times, a spiritual safe haven for merchants crossing the Persian Gulf.

Tell Abraq’s layers read like a historical core sample: more than 3,000 years of uninterrupted human occupation, beginning around 2500 BCE and extending into the late antique era. While southeastern Arabia never developed large state systems like those of Mesopotamia or Elam, the site’s unique stratigraphy shows that it was deeply plugged into long-distance commercial and cultural networks. The new research confirms two major phases of intense cross-cultural exchange: one in the Late Bronze Age (around 1600–1300 BCE) and another in the first to third centuries CE.

A Bronze Age Trade Control Center Hidden Beneath the Sands

One of the most striking discoveries is Building B-I, a monumental stone structure built between the late 14th and early 13th centuries BCE. According to the research team, led by Dr. Michele Degli Esposti of the Polish Academy of Sciences, the building is unlike anything else known in Arabia. Its walls were bonded with a remarkably hard mortar—a construction technique with no regional parallel.

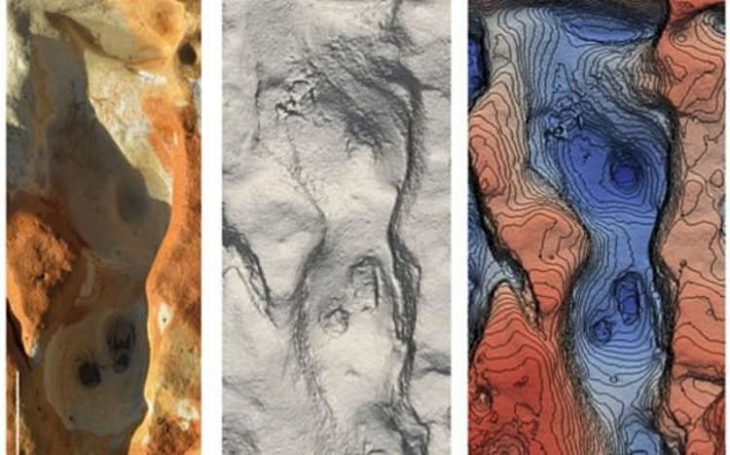

Inside, archaeologists found a cache of imported pottery, particularly medium-sized storage jars made from dense, sandy clays typical of southeastern Iran. Two of these jars bore cylinder-seal impressions, featuring iconography connected to South Mesopotamia and Elam. The impressions—detailed motifs pressed into wet clay before firing—confirm the vessels’ foreign origins.

📣 Our WhatsApp channel is now LIVE! Stay up-to-date with the latest news and updates, just click here to follow us on WhatsApp and never miss a thing!!

Even more telling, the original floor of B-I preserved the hollows where the jars once stood, indicating that imported goods were processed or stored on site. The relative scarcity of imported pottery elsewhere at Tell Abraq suggests the building served as a controlled redistribution point, perhaps operated by foreign agents representing Kassite or Elamite interests.

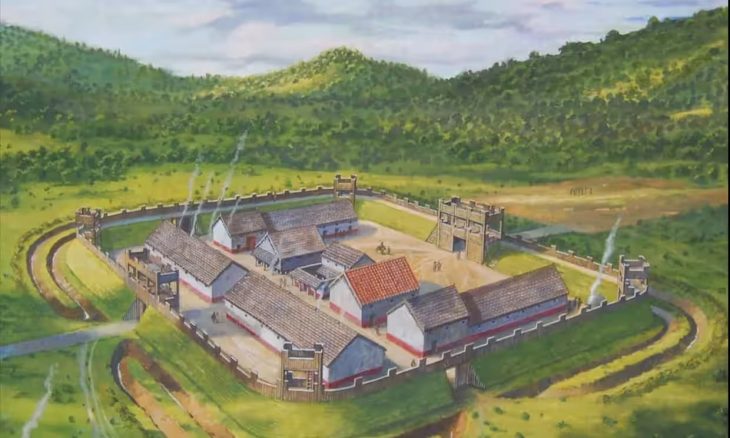

In other words, this was not simply a warehouse—it may have been a trade oversight station, a checkpoint monitoring the flow of goods through southeastern Arabia during a period when Gulf commerce was heavily shaped by external powers.

A Quiet Period—Then a Spiritual Rebirth

After this vibrant Late Bronze Age phase, Tell Abraq’s outward-facing connections dimmed. During Iron Age II (1100–600 BCE), the site shows mostly domestic activity and reused kilns, with almost no imported materials. But centuries later, something extraordinary happened: Tell Abraq evolved from a residential settlement into a sanctuary.

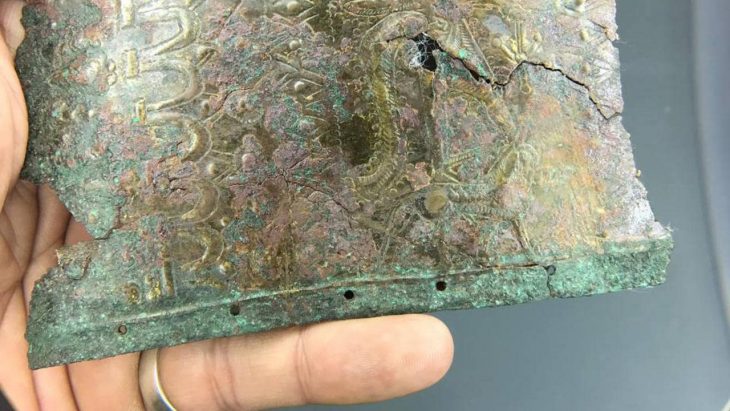

By the first to third centuries CE, the tell was dominated not by homes or workshops, but by a small cultic building known as B-III, complete with an open-air altar. Here, archaeologists uncovered a stunning collection of offerings:

At the heart of this sanctuary, archaeologists uncovered an extraordinary mix of artifacts that spoke to the site’s far-reaching connections: clay and bronze figurines crafted in Hellenistic styles, locally minted bronze coins circulating alongside carefully made imitations of Roman aurei, stone statues whose features pointed south toward the cultures of Arabia, and even a rare Aramaic inscription—the language that once linked merchants from Mesopotamia to the Levant. Together, these offerings paint a vivid picture of a place where travelers from multiple worlds paused to seek protection, express gratitude, and renew their ties to the divine before continuing their journeys across the Persian Gulf.

These objects reveal a dense web of interaction connecting southeastern Arabia to the Roman Levant, southern Mesopotamia, India, and the wider Arabian Peninsula. The sanctuary appears to have been a spiritual waypoint for merchants traveling by land and sea—similar to the nearby Sun-God temple at Ed-Dur—where traders could seek divine protection before navigating the hazardous crossing of the Persian Gulf.

A Strategic Outpost in the Theater of Ancient Globalization

The artifacts from B-III coincide with a period when trade in the Gulf was dominated by the Characene kingdom, a Parthian-era polity controlling the head of the Persian Gulf. Unlike the earlier Bronze Age phase, where foreign powers may have exerted direct oversight within Tell Abraq, the Roman-era influence appears purely commercial, reflected in the eclectic and cosmopolitan nature of the votive offerings.

Across all periods, one pattern stands out: the arrival of exotic goods at Tell Abraq spikes during times of strong external political presence in the Gulf. Yet the site remained resilient and adaptable, shifting roles as geopolitical winds changed—from residential hub to trade checkpoint to sacred refuge.

Where Land Meets Sea, History Meets the Present

Today, Tell Abraq offers archaeologists a rare, nearly uninterrupted chronological sequence spanning three millennia. Few sites in the Gulf can match its continuity or its capacity to illuminate how local communities engaged with the broader ancient world.

Ultimately, the story emerging from Tell Abraq is one of connectivity, adaptation, and cultural convergence. A modest mound overlooking the Gulf has revealed itself to be a key node in the global networks of antiquity—a place where traders from far-flung regions paused to rest, trade, worship, and continue their journeys across the waters that linked continents.

Degli Esposti, M. (2025). Tell Abraq: cross-cultural connections in the Persian Gulf from the Late Bronze Age to the early centuries AD. Antiquity, 1–8. doi:10.15184/aqy.2025.10246

Cover Image Credit: Degli Esposti 2025, Antiquity