An Italian archaeological mission, the Erimi Archaeological Project of the University of Siena, discovered a 4,000-year-old temple in Cyprus. This is the oldest sacred space ever found on the island.

The discovery was made in collaboration with the Cypriot Department of Antiquities and the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs and International Cooperation.

The temple provides a glimpse into the past of the island’s artisan community and is characterized by an enigmatic central monolith adorned with a circular motif of small cups.

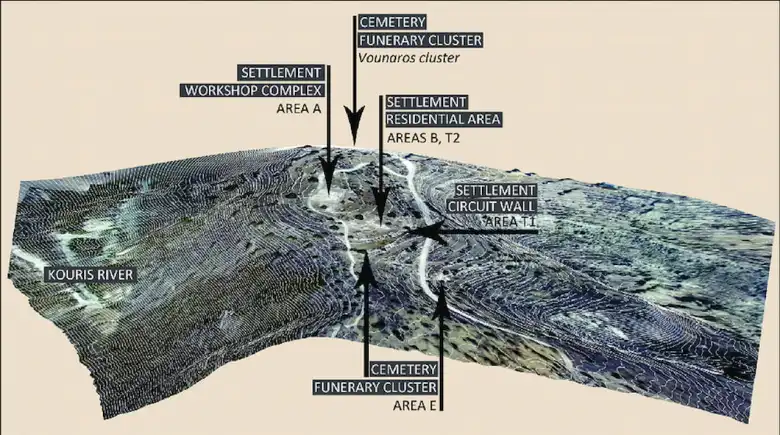

Over fifteen years, under the direction of archaeologist Luca Bombardieri, the excavation revealed a temple-like building tucked away inside a sizable workshop complex. This “temple before the temple,” as Bombardieri puts it, illuminates the pivotal role that religion played in these prehistoric peoples’ lives. The complex, which spanned more than 1000 square meters and was built during the Middle Bronze Age (2000–1600 BC), contained dyeing vats, warehouses, and workshops.

Located on a hilltop near present-day Limassol, the site offered optimal conditions for their craft, with ample ventilation, freshwater sources, and readily available dye plants.

📣 Our WhatsApp channel is now LIVE! Stay up-to-date with the latest news and updates, just click here to follow us on WhatsApp and never miss a thing!!

According to Bombardieri, the primitive settlement of Erimi is situated inland from Limassol and spans a high limestone terrace with views over the Kouris River’s course, a sizable stretch of the Kourion Gulf’s coast, and the Akrotiri Peninsula. A group of craftsmen chose to settle on the Erimi hill during the Middle Bronze Age (c. 2000–1600 BC), creating a distinctive community area.

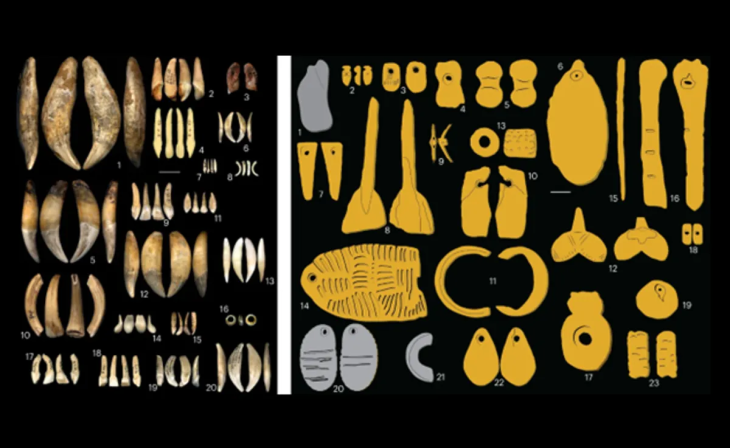

The temple itself, accessed through the bustling work areas, housed a striking 2.30-meter monolith, a brazier, and a large amphora – elements suggesting ritual practices. Bombardieri speculates that the community’s leaders, likely those overseeing production, might have also served as spiritual guides.

Bombardieri describes: The monolith, which originally stood in the center of the room, collapsed onto the floor, destroying a large amphora placed at its feet, in front of a small circular hearth. The internal space of this room allowed circulation around the monolith, the amphora, and the hearth, which occupied the central part. The peculiarities of this space, especially in comparison with the surrounding spaces of the production workshop, indicate that it is a small sacred space, the oldest recorded on this island, with an interesting cult function due to its location within the workshop complex. Thus, the activity that economically sustained the community also involved its members ideologically and symbolically.

The excavation revealed more than just prehistoric ritual and industry. An additional layer of mystery surrounds the site after a horrifying discovery: the remains of a young woman who was brutally murdered and her home walled up. A large stone lay across her chest, and her skull showed the scars of a deadly blow, probably from a spear or stone. The sealed doorway and lack of grave goods point to a purposeful act of separation that may be connected to societal concerns about motherhood, as Bombardieri hypothesizes.

Renowned for its vivid red fabrics, the Erimi settlement seems to have thrived, possibly developing into a proto-city. Its tale, though, concludes suddenly. Aside from the temple with its massive monolith, the village had been abandoned, the workshops sealed, and tools and materials still inside. The site was ironically preserved for millennia after a fire—possibly started by the emigrating residents—caused the roof to fall.

This Italian research program has involved the collaboration of numerous institutions, including the Cyprus Institute and the INFN-Labec, as well as the support of the Mediterranean Archaeological Fund and the Aegean Prehistory Institute.

This research project’s primary goal is to offer new data for the examination of production and cultural relations during the shift to urban society in this significant insula, which is located between the Mediterranean and the Near East.

Cover Photo: University of Siena