Dogs have been the best friend of humans since ancient times. Although it is not known exactly when dogs were included in human life, it is possible to say that this history goes back every day.

A team of archaeologists from the northwestern Kingdom of Saudi Arabia has uncovered the earliest evidence of dog domestication by the region’s ancient peoples.

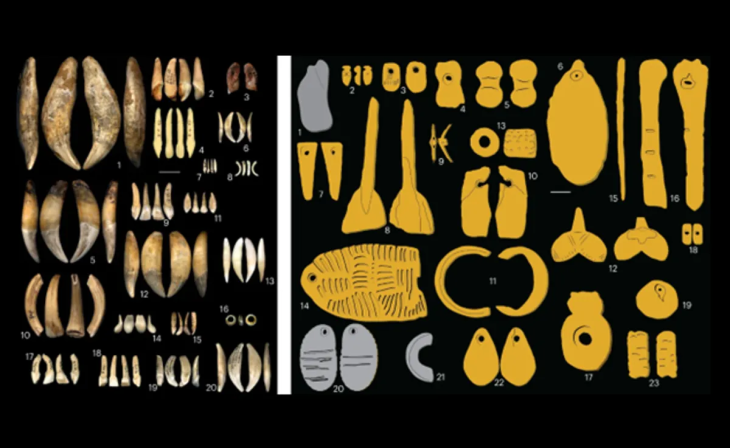

Recent excavations by the Aerial Archeology project in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (AAKSA) have found substantial skeletal material, evidence for funerary offerings, including jewelry, and the earliest chronometrically dated domestic dog in the Arabian Peninsula.

Evidence suggests that the earliest use of the tomb was around 4300 B.C. and was buried for at least 600 years in the Neolithic-Chalcolithic era – an indication that the inhabitants may have had a common memory of people, places, and the connections between them.

“What we are finding will revolutionize how we view periods like the Neolithic in the Middle East. To have that kind of memory, that people may have known for hundreds of years where their kin was buried – that’s unheard of in this period in this region,” said Melissa Kennedy, assistant director of the Aerial Archaeology in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (AAKSAU) – AlUla project.

📣 Our WhatsApp channel is now LIVE! Stay up-to-date with the latest news and updates, just click here to follow us on WhatsApp and never miss a thing!!

“AlUla is at a point where we’re going to begin to realize how important it was to the development of mankind across the Middle East,” said the AAKSAU director, Hugh Thomas.

This is the earliest evidence of a domesticated dog in the Arabian Peninsula by a margin of circa 1,000 years.

The project team, together with Saudi Arabia and international members, focused their work on two above-ground cemeteries from the 5th to 4th centuries BC, 130 kilometers apart, one on the volcanic heights and the other on the arid wasteland. The research team discovered these locations by using satellite images and then taking aerial photographs by helicopter. The ground field survey started at the end of 2018.

At the scene of the volcanic highlands, 26 bone fragments of a dog were found, as well as bones of 11 people-six adults, one teenager, and four children.

The dog’s bones showed signs of arthritis, suggesting that the animal lived with humans to middle age or old age.

After assembling the bones, the team then had to determine that they were from a dog and not from a similar animal such as a desert wolf. Zoo archaeologist Laura Strolin was able to show that it was indeed a dog by examining, in particular, one bone on the animal’s left front leg. The width of this bone was 21.0 mm, which corresponds to the range of other ancient Middle Eastern dogs. For comparison, the wolves of that time and place were 24.7 to 26 mm wide for the same bone.

The dog’s bones were dated between circa 4200 and 4000 BCE.

The rock art found in the area shows that the Neolithic residents used dogs and other animals when hunting ibexes.

The researchers expect more findings in the future as a result of the massive survey from the air and on the ground, and the multiple targeted excavations in the AlUla region conducted by the AAKSAU and other teams, operating under the auspices of the Royal Commission for AlUla.

The findings are published in the Journal of Field Archaeology