The death rate of newborns in ancient cultures is not a reflection of inadequate healthcare, sickness, or other issues, according to a recent study from The Australian National University (ANU), but rather an indicator of the number of babies born in that era.

When compared to today, when we have access to modern healthcare, infant mortality was quite high in ancient times. Bones from hunter-gatherer burial sites indicate that approximately half of all newborns born in prehistoric times died during their first year of life.

However, a recent study conducted by Australian academics depicts a starkly different picture, suggesting that previously published death statistics are almost certainly incorrect.

The findings offered new insight into our ancestors’ past and disproved long-held beliefs that ancient populations had persistently high infant mortality rates.

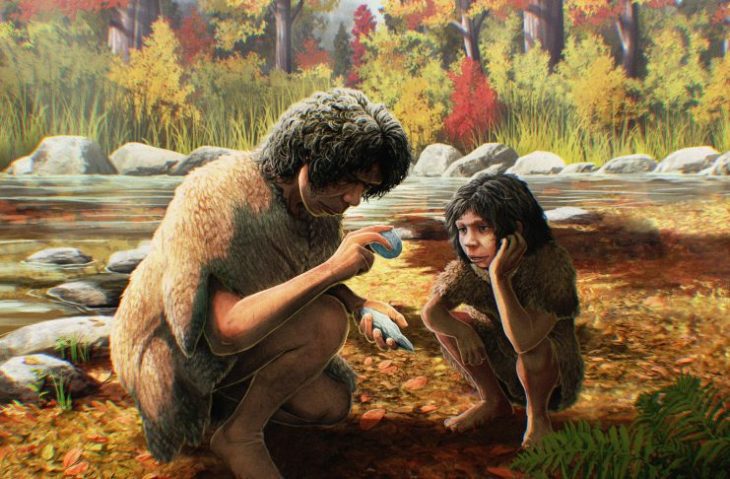

The study also opens up the possibility mothers from early human societies may have been much more capable of caring for their children than previously thought.

📣 Our WhatsApp channel is now LIVE! Stay up-to-date with the latest news and updates, just click here to follow us on WhatsApp and never miss a thing!!

“It has long been assumed that if there are a lot of deceased babies in a burial sample, then infant mortality must have been high,” lead author Dr. Clare McFadden, from the ANU School of Archaeology and Anthropology, said in a statement.

“Many have assumed that infant mortality was very high in the past in the absence of modern healthcare.”

“When we look at these burial samples, it actually tells us more about the number of babies that were born and tells us very little about the number of babies that were dying, which is counterintuitive to past perceptions.”

Dr. Clare McFadden and colleagues went through a vast United Nations dataset on infant mortality, fertility, and deaths in infancy from 97 nations. This study found that fertility, rather than mortality rate, had a far bigger impact on the proportion of dead newborns. The bigger the number of children born, the greater the proportion of infants that died early.

If that’s the case in today’s environment, it’s likely that the same thing happened in ancient times, with the exception that the size of the influence was far bigger. The researchers took an intellectual leap based on the UN data and concluded that physical burial samples from the last 10,000 years do not support the assumption that infant mortality was as high as 40%, as some have asserted before based on archaeological evidence. In other words, despite what may appear to be a paradox, the large number of baby graves represents a high level of fertility, implying that ancient parents had the means and ability to raise a large number of children.

“Burial samples show no proof that a lot of babies were dying, but they do tell us a lot of babies were being born,” McFadden said.

“If mothers during that time were having a lot of babies, then it seems reasonable to suggest they were capable of caring for their young children.”

We still know very little about what it was like to be a mother thousands of years ago. When did women become moms for the first time, and how many children did they have on average? Nobody knows, and we’re unlikely to ever uncover definitive answers. Instead, we have a plethora of assumptions, some of which are more prone to mistake than others.

Dr. McFadden said as we piece together more clues about the history of humans, it’s important we “bring some humanity” back to our ancestors.

“Artistic representations and popular culture tend to view our ancestors as these archaic and incapable people, and we forget their emotional experience and responses such as the desire to provide care and feelings of grief date back tens of thousands of years, so adding this emotional and empathetic aspect to the human narrative is really important,” she said.

“We hope that further research, applied with the lens of our findings, will add to our understanding of infant care and motherhood in the past.”

The findings appeared in the American Journal of Biological Anthropology.

Cover photo: Scroll.in