For a civilisation that flourished more than 3,000 years ago, the Hittites may have been far more concerned with cleanliness and hygiene than previously assumed. A newly published study in Anatolian Studies challenges modern stereotypes about ancient societies, revealing that hygiene in Hittite culture was not incidental—but structured, meaningful, and deeply embedded in daily life, religion, and social hierarchy.

The research, authored by Ana Arroyo of the Complutense University of Madrid, examines how the Hittites understood cleanliness, how often they washed, what materials they used, and where these practices took place. Drawing on cuneiform texts and archaeological evidence, the study paints a surprisingly vivid picture of hygiene in Late Bronze Age Anatolia.

Hygiene Was More Than Washing

One of the study’s key findings is that there was no single, universal definition of cleanliness in Hittite society. Instead, hygiene operated at the intersection of physical care, social norms, and religious expectations. While modern concepts of hygiene are closely tied to disease prevention, Hittite ideas were broader—concerned with removing dirt, avoiding contamination, and maintaining a state suitable for interaction with both people and gods.

Water played a central role. Hittite texts repeatedly describe washing, bathing, and rinsing with water as essential actions, whether for everyday cleanliness or ritual preparation. In some cases, water itself was described as inherently “clean” and capable of cleansing both objects and individuals.

Soap, Ash, and Early Detergents

Perhaps most striking is the evidence that the Hittites used detergent-like substances to enhance cleaning. The study documents the use of natron, ash, and plant-based materials comparable to soapwort—ingredients known to improve water’s cleansing properties.

📣 Our WhatsApp channel is now LIVE! Stay up-to-date with the latest news and updates, just click here to follow us on WhatsApp and never miss a thing!!

These substances were mixed with water to wash clothing, utensils, religious statues, and even people. In ritual texts, dirty linen is described as being turned white through washing, an image that strongly echoes modern expectations of cleanliness. The language used suggests not symbolic action alone, but practical cleaning that removed visible dirt.

Bathtubs in Hittite Homes and Temples

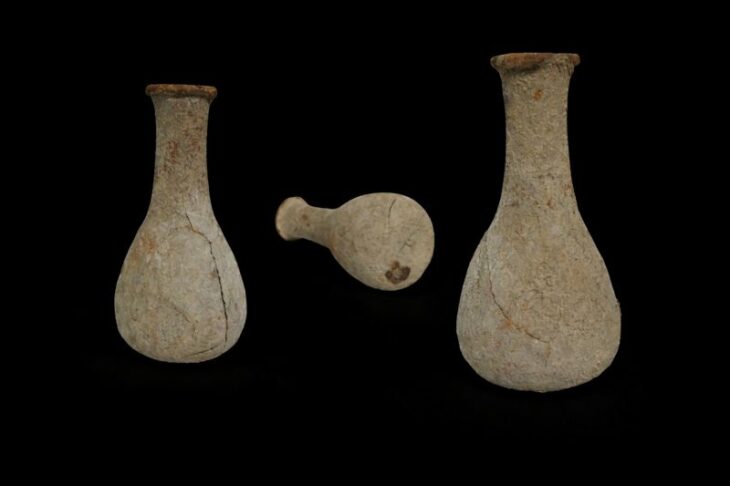

Archaeology supports the textual evidence. Excavations at major Hittite sites such as Ḫattuša, Šarišša, Oymaağaç, and Tarsus have uncovered ceramic bathtubs, many of them large, carefully shaped, and connected to drainage systems.

These tubs were often found in rooms with waterproof floors, interpreted as washrooms or bathrooms. Some even featured built-in seats, handles for emptying water, and traces of surface treatment. In several cases, vessels likely used for oils or pouring water were discovered nearby, reinforcing the interpretation of these spaces as dedicated hygiene areas.

Notably, scholars suggest that nearly every house may have had a bathtub, at least in some Hittite cities—a claim that challenges assumptions about domestic life in the Late Bronze Age.

Cleanliness and Social Status

Hygiene was not practiced equally by all. The study highlights how social rank influenced access to clean spaces and objects. Royal and elite contexts featured washbasins made of copper, bronze, and even silver. These were not symbolic miniatures but heavy, functional items designed for regular use.

Texts describing palace life show an intense concern with contamination. In one striking anecdote, a Hittite king becomes enraged after finding a single hair in his wash water, ordering stricter filtering procedures. The incident underscores how cleanliness was closely tied to royal dignity and authority.

Washing Before the Gods

Cleanliness was also a prerequisite for religious activity. Priests, temple workers, and even bakers preparing bread for the gods were required to be bathed, groomed, and dressed in clean garments. Hair and nails had to be trimmed; clothing had to be freshly washed.

Before rituals, kings and queens washed their hands, wiped them with cloths, and followed carefully prescribed sequences of cleansing. These actions were not optional. Being physically unclean could render a person unfit to approach the divine.

Yet the study emphasizes an important distinction: being clean did not automatically mean being ritually pure. Cleanliness was necessary, but not always sufficient. Ritual procedures were often required to restore full religious purity after certain actions or exposures.

A More Nuanced View of Ancient Life

Taken together, the evidence reveals a culture with a highly developed understanding of hygiene, one that blended practical cleaning with symbolic meaning. The Hittites filtered water, used detergents, built bathrooms, and enforced cleanliness rules—practices that resonate strongly with modern expectations.

Rather than viewing ancient hygiene as primitive or purely ritualistic, this research invites a reassessment. The Hittites were not indifferent to dirt. On the contrary, cleanliness shaped their homes, their rituals, and their social order.

As Arroyo’s study demonstrates, ancient Anatolia was not only a land of kings, gods, and treaties—but also of baths, soap, and a surprisingly modern concern for staying clean.

Arroyo A. Hittite cultural conventions on hygiene. Anatolian Studies. 2025;75:29-45. doi:10.1017/S0066154625000055

Cover Image Credit: AI-generated illustrative image representing hygiene practices in Hittite society. The scene reflects the author’s interpretation based on archaeological and textual evidence, and does not depict a specific historical event.