Ancient tally sticks — carved wooden and bone records of debts and taxes — are rewriting what we thought we knew about the origins of money.

For centuries, textbooks and popular economics have taught a simple narrative: early humans bartered, then invented money to solve barter’s inefficiencies, eventually giving rise to coins, paper bills, and digital balances. But new research led by University at Albany anthropologist Robert M. Rosenswig argues that this story is a myth — and that the real roots of money tell us more about politics than markets.

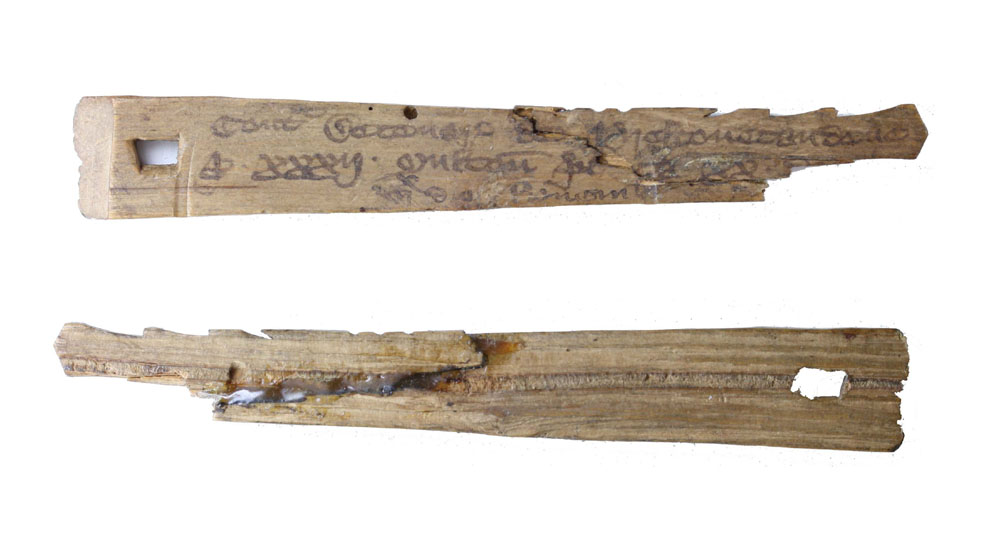

His study, “Ancient Tally Sticks Explain the Nature of Modern Government Money,” published in the Journal of Economic Issues, demonstrates that money did not emerge as a universal medium of exchange. Instead, evidence from ancient tally sticks — wooden or bone devices used in England, China, and the Maya world — shows that money began as a system of accounting and taxation rooted in state authority.

From Barter Myth to Political Reality

The orthodox economic story claims that barter was humanity’s first economic system. Because barter required the “double coincidence of wants,” markets supposedly needed a universal medium like salt, gold, or silver. This version is still found in Econ 101 courses and mainstream sources like Investopedia.

But Rosenswig pushes back:

📣 Our WhatsApp channel is now LIVE! Stay up-to-date with the latest news and updates, just click here to follow us on WhatsApp and never miss a thing!!

“The historical record shows that barter doesn’t precede the creation of financial money. Tally sticks remind us that money is not a scarce commodity but an accounting system rooted in political authority.”

Anthropological evidence supports this. Barter did occur — but only in societies that already had money, usually during currency shortages or in one-off exchanges between strangers. It was never the foundation of whole economies.

Tally Sticks Across Civilizations

Rosenswig’s research compares tally sticks in three civilizations that never had contact with each other, yet independently created remarkably similar tools:

England: From the 12th century onward, sheriffs issued hazelwood sticks to record taxes for the Exchequer. Some evolved into circulating debt instruments called “assignment tallies.” One surviving stick, more than eight feet long, records a £1.2 million loan to King William III — a debt technically never repaid.

China: Starting in the 3rd century BCE, officials split bamboo tallies to track grain, silk, and coin receipts. Marco Polo observed their use in the 13th century, long after the system began. Their durability and resistance to forgery made them reliable tools of state accounting.

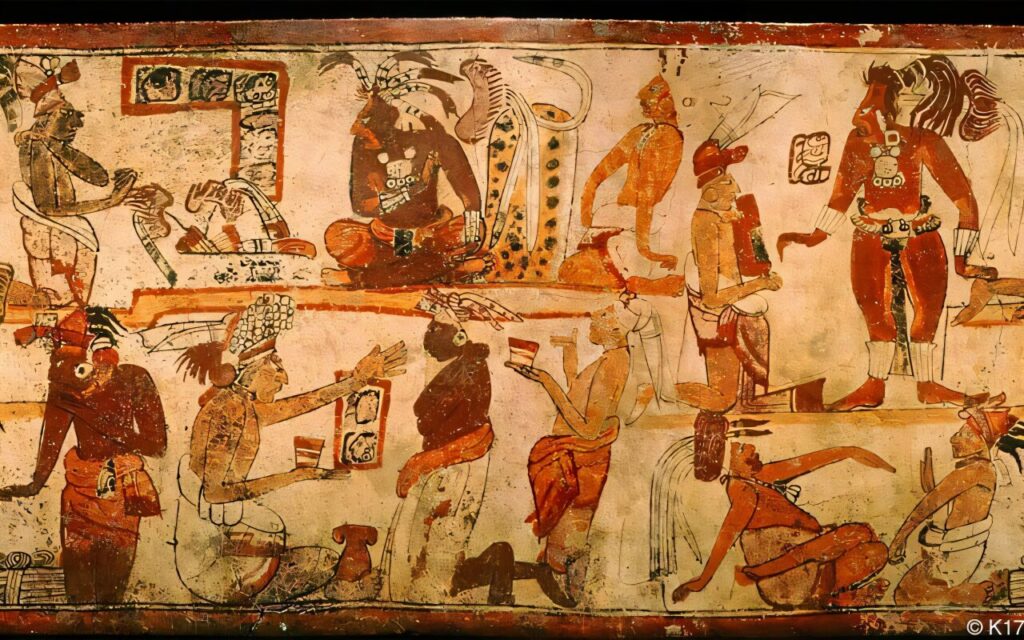

Maya Civilization: Bone tally sticks from 600–900 CE feature royal burials and court scenes. They recorded tribute in maize, textiles, or labor rather than market transactions.

“These examples are powerful because they come from societies with no historical connection,” Rosenswig explains. “Yet each independently developed tally sticks as a way to mobilize resources through state authority.”

Chartalism and the Politics of Money

The findings strongly support the chartalist view of money: that money originates as a unit of account enforced by governments to administer taxes and obligations. This directly challenges orthodox economics, which treats money as a neutral medium of exchange.

The study also engages with social positioning theory, which frames money as a community-wide relationship built on social trust. While tally sticks align most closely with chartalism, they also show that not all money accounts for financial debt — some record social relationships and obligations, broadening our understanding of monetary forms.

Why It Matters Today

If money originates with governments, not markets, modern economic policy debates look different. Rosenswig argues that the “household analogy” — the idea that governments must live within their means just like families — is historically unfounded.

“Fiscally sovereign governments spend first, then tax to regulate inflation and demand,” he notes. “Once unshackled from the orthodox assertion that financial money is primarily a medium of exchange, governments are free to support working men and women during downturns of our modern capitalist economy.”

This perspective directly challenges austerity policies that treat state spending as tightly limited. Instead, it suggests governments have more flexibility to invest in social programs, infrastructure, and crisis relief.

Reframing Economics Through Anthropology

For Rosenswig, the broader lesson is that anthropology matters for public debate. Understanding how ancient societies managed resources can reshape our assumptions about modern economies.

“Studying the past reminds us that money is not timeless or universal in form,” he says. “It is a political tool, and how we choose to use it today is a matter of policy, not natural law.”

His study reinforces earlier research distinguishing social, government, and private money and highlights the importance of political authority in financial systems. Far from being a neutral facilitator of trade, money is — and always has been — a product of institutional power.

Key Takeaway

The history of money is far more complex than the familiar tale of barter evolving neatly into coins, paper, and digital balances. Evidence from ancient tally sticks strongly suggests that money began as a political and institutional tool of accounting and taxation rather than as a market invention.

Still, this is not the final word. As new archaeological discoveries and theoretical perspectives emerge, our understanding of money’s origins may continue to shift. What Rosenswig’s study makes clear is that we should be cautious about accepting simplified narratives — and remain open to the possibility that money, in all its forms, reflects multiple pathways shaped by politics, culture, and human creativity.

Rosenswig, R. M. (2025). Ancient Tally Sticks Explain the Nature of Modern Government Money. Journal of Economic Issues, 59(3), 663–685. https://doi.org/10.1080/00213624.2025.2533734

Cover Image Credit: Medieval English split tally stick (front and back). The notches and inscriptions record a debt owed to the rural dean of Preston Candover, Hampshire: a tithe of 20d each on 32 sheep, totaling £2 13s. 4d. Public Domain