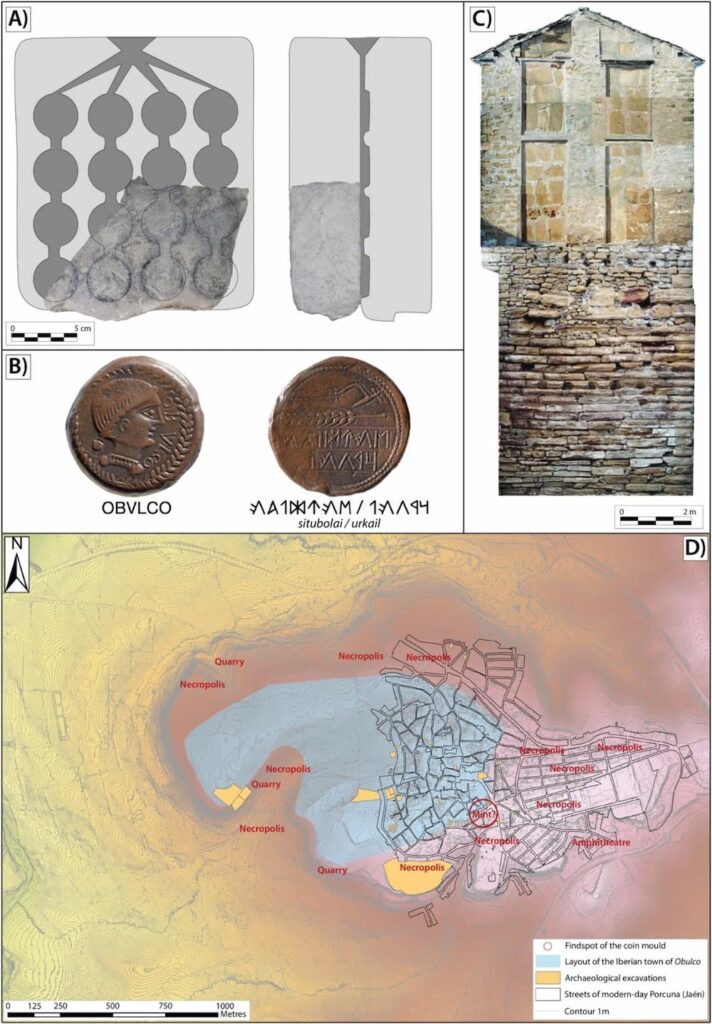

Researchers from the University of Jaén have made a groundbreaking discovery at the archaeological site of Obulco, modern-day Porcuna, revealing the earliest known stone mold used for coin production in the Roman province of Hispania. This significant finding was first reported by La Brújula Verde, highlighting the importance of the discovery in understanding ancient monetary practices.

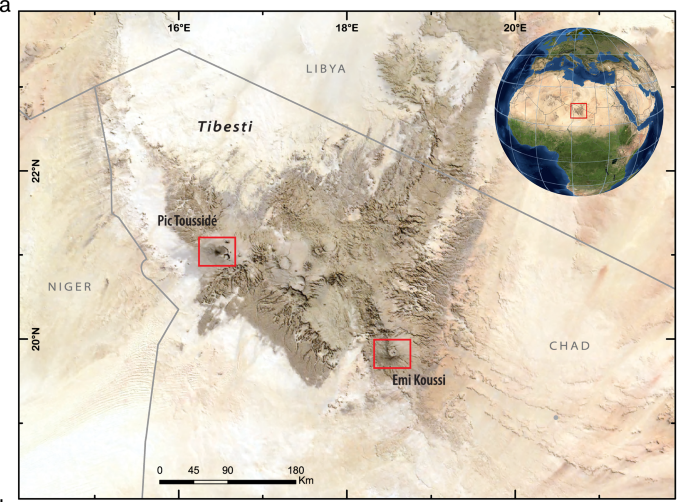

The archaeological site of Obulco, located in modern-day Porcuna, Spain, was an important Ibero-Roman settlement during the ancient period. It flourished particularly during the 2nd century BCE, serving as a key economic and cultural center in the region. Obulco was known for its strategic location along trade routes and its active mint, which produced coins that reflect the integration of local and Roman influences.

From the late 3rd century to the 1st century BCE, numerous mints emerged across the Iberian Peninsula, producing coins either regularly or sporadically. Despite the wealth of coin emissions, tangible evidence of the production workshops has been scarce, often limited to the coins themselves found in various archaeological contexts. This scarcity has raised questions about the physical locations of the mints, the production chain, and the social structures surrounding these artisanal spaces.

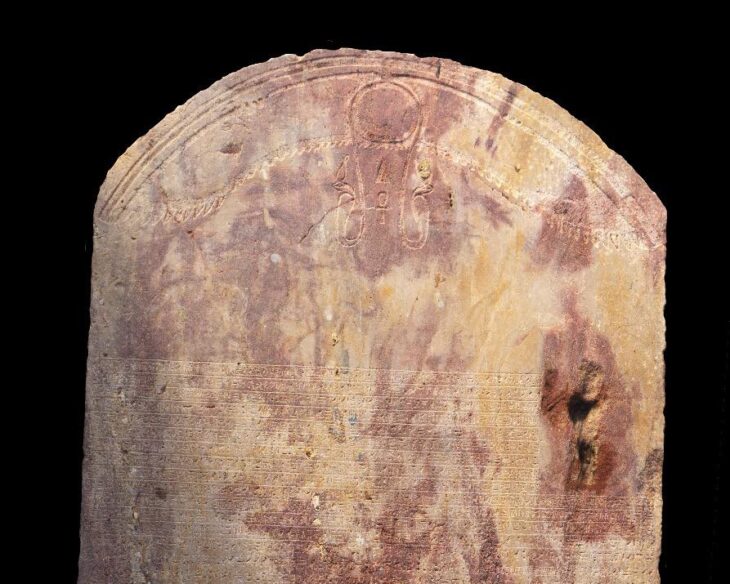

The recently uncovered stone mold, measuring approximately 11 cm in height, 13.7 cm in length, and 5.4 cm in width, is one half of a bivalve mold used to create coin blanks—raw, unminted metal discs that would later be stamped into coins. The mold features a flat surface with circular casting marks and signs of thermal use, indicating its role in the coin-making process. Petrographic analysis confirmed that the stone used for its manufacture originated from the local geological unit of Porcuna, highlighting the resource exploitation for industrial tool-making in antiquity.

X-ray fluorescence spectrometry analysis revealed a binary copper-lead alloy in the mold’s metallic impressions, consistent with the compositions found in coins from Obulco. Researchers have linked this mold to the production of bronze asses dated between 189 and 165 BCE, marking it as part of one of the first coin series issued by the city.

📣 Our WhatsApp channel is now LIVE! Stay up-to-date with the latest news and updates, just click here to follow us on WhatsApp and never miss a thing!!

Obulco, a key city in the Upper Guadalquivir region during the Iberian and Roman periods, was one of the most active mints in southern Hispania, issuing coins from the late 3rd century to the 1st century BCE. The iconography of its coins reflects the city’s integration into the Roman economic system, featuring agricultural motifs that symbolize the local economy’s reliance on cereal production.

The mold’s discovery in a suburban area near the city’s fortifications raises intriguing questions about the mint’s location within Obulco’s urban layout. Similar findings at Carteia, another identified mint, suggest that minting workshops may have been situated in peripheral areas under local magistrates’ or military control.

This mold not only provides insights into the technical aspects of coin production but also reflects the socioeconomic changes driven by Roman expansion in Hispania. Coins minted in Obulco during the 2nd century BCE bear the names of local magistrates inscribed in both Iberian and Latin characters, illustrating the gradual assimilation of Roman administrative practices within indigenous communities.

The increasing monetary production during this period coincides with the territorial reorganization and expansion of cereal agriculture, linked to the Roman Republic‘s extractive economic system. Thus, the Obulco mold serves as a tangible indicator of the transformations experienced by Iberian cities as they integrated into the Roman imperial framework.

This remarkable discovery not only addresses the long-standing archaeological gap regarding the visibility of mints but also paves the way for new research opportunities focused on the locations and operations of these critical economic spaces in Republican Hispania.

By shedding light on the intricacies of coin production, this find contributes significantly to our understanding of the multifaceted economic, political, and social dynamics that influenced the Romanization of the Iberian Peninsula. Furthermore, it highlights the pivotal role that coinage played in facilitating these transformations, serving as a vital link between local communities and the broader Roman economic system. As researchers delve deeper into the implications of this mold, it is expected to enrich our comprehension of how ancient societies adapted to and integrated with the expanding Roman influence.

María Isabel Moreno-Padilla, Mario Gutiérrez-Rodríguez, et al., Dealing with the archaeological invisibility of the Iberian mints: A technological and contextual analysis of the first stone mould for blank coin production found in Hispania. Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports, Volume 63. Doi.org/10.1016/j.jasrep.2025.105083

Cover Image Credit: Detailed images of the stone mould used for blank coin production. It corresponds to the flat valve of a bivalve mould. Credit: M.I. Moreno-Padilla et al.