A newly published preliminary study has reignited one of archaeology’s most enduring controversies: when was the Great Pyramid of Giza actually built?

In a paper released in January 2026, Italian engineer Alberto Donini presents an unconventional dating approach—known as the Relative Erosion Method (REM)—which he argues may challenge the long-accepted chronology placing the construction of the Pyramid of Khufu around 2560 BC. According to Donini’s calculations, erosion patterns at the pyramid’s base could suggest a construction date tens of thousands of years earlier, potentially as far back as the late Paleolithic period.

The claim, if substantiated, would have far-reaching implications for the history of ancient Egypt and early civilization. Yet it also raises immediate questions about methodology, assumptions, and how such results should be interpreted within archaeological science.

Dating Stone Through Erosion

At the core of Donini’s work is REM, a method designed to estimate the age of stone structures by comparing relative erosion on adjacent rock surfaces made of the same material and exposed to the same environment.

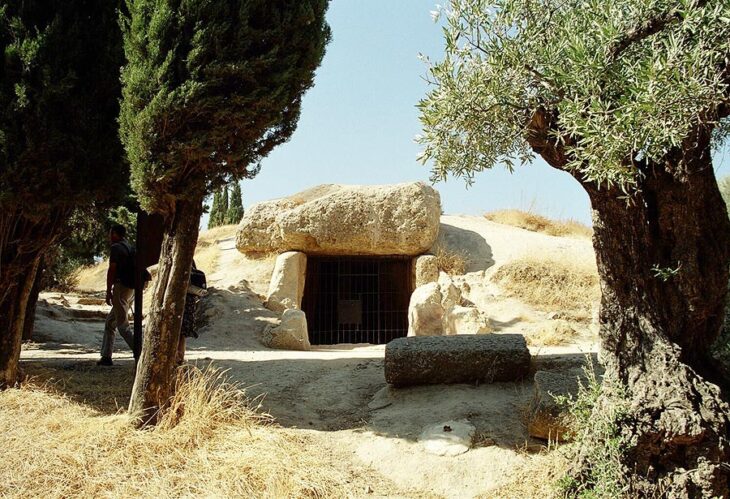

The logic is straightforward. At Giza, much of the Great Pyramid was once covered with smooth limestone casing blocks. Historical sources indicate that these casing stones were systematically removed and reused in Cairo after major seismic events—particularly following the powerful earthquake of 1303 AD—and during the Mamluk period. This means that some limestone surfaces at the pyramid’s base have been exposed to wind, moisture, salts, and foot traffic for roughly 675 years, while neighboring surfaces have remained exposed since the monument’s original construction.

📣 Our WhatsApp channel is now LIVE! Stay up-to-date with the latest news and updates, just click here to follow us on WhatsApp and never miss a thing!!

By measuring the difference in erosion between these two surfaces, Donini argues, it is possible to calculate how long the older surfaces must have been exposed.

Measuring Wear at the Base of the Pyramid

The study focuses on twelve measurement points around the base of the Great Pyramid. At each point, Donini examined either pitting erosion—small cavities formed by chemical and physical weathering—or uniform surface wear, estimating the volume or depth of material lost.

In one representative example, a pavement slab shows deeply pitted erosion on the side exposed since the pyramid’s construction, compared with much shallower erosion on the side uncovered only after the casing stones were removed. Using the ratio between these two erosion volumes and applying a linear erosion model, Donini calculates an exposure time of over 5,700 years before present for that point alone.

Other points yield far higher values. Several measurements suggest erosion equivalent to 20,000 to more than 40,000 years of exposure, while the arithmetic mean of all twelve points produces a result of approximately 24,900 years before present, corresponding to roughly 22,900 BC.

Probability, Not Precision

Donini emphasizes that REM is not intended to provide an exact construction date. Instead, it estimates an order of magnitude. To address uncertainty, the study applies a basic statistical analysis, calculating a standard deviation and constructing a Gaussian probability curve.

Based on this model, the report concludes that there is a 68.2% probability that the Great Pyramid was constructed sometime between roughly 9,000 BC and 36,000 BC, with the highest probability centered around the early 20,000s BC.

The author stresses that these conclusions are preliminary and invites further measurements and collaboration.

Sources of Uncertainty

The paper openly acknowledges numerous factors that could affect erosion rates over time. Climate conditions in ancient Egypt were likely wetter than today, potentially accelerating erosion in the distant past. Conversely, modern pollution and acid rain may have increased erosion rates in recent centuries, possibly skewing comparisons.

Human activity is another complicating factor. The base of the Great Pyramid now receives thousands of visitors daily, whereas foot traffic in antiquity would have been far lighter. Periodic burial of stone surfaces beneath sand—similar to what occurred at the Sphinx—may also have shielded parts of the pyramid from erosion for long intervals.

Because of these variables, Donini argues that individual measurement points may overestimate or underestimate age, but that averaging multiple points reduces error.

A Challenge to Established Chronology

The REM-based dates stand in sharp contrast to the conventional Egyptological timeline, which relies on historical records, inscriptions, tool marks, radiocarbon dating of associated organic material, and broader archaeological context to place Khufu’s reign firmly in the Fourth Dynasty of the Old Kingdom.

Donini suggests that this discrepancy could mean the pyramid predates Khufu and was merely renovated or repurposed during his reign—a hypothesis long present in fringe literature but rejected by mainstream scholarship.

At present, the study has not undergone peer review in a major archaeological journal, and its conclusions remain outside academic consensus. Most archaeologists caution that erosion rates are highly variable and difficult to model linearly over tens of thousands of years.

An Ongoing Debate

Whether REM will prove to be a useful complementary tool or a methodological dead end remains to be seen. What is certain is that the study underscores how even the most iconic monuments of the ancient world can still provoke fundamental questions.

For now, the Great Pyramid remains securely anchored in the Old Kingdom—yet studies like this ensure that debates about its origins are far from settled. As Donini himself notes, further measurements and independent verification will be essential before such extraordinary claims can be meaningfully assessed.

Donini, A. (2026). Preliminary report on the absolute dating of the Khufu Pyramid using the Relative Erosion Method (REM). University of Bologna. DOI:10.5281/zenodo.18315238

Cover Image Credit: Public Domain – Wikipedia Commons