As the archaeological discoveries at Kansala, located in present-day Guinea-Bissau, reveal the tangible remnants of the once-mighty Kaabu Kingdom, the echoes of griots’ songs remind us that the rich tapestry of oral tradition holds the key to understanding a history that has long been shrouded in mystery.

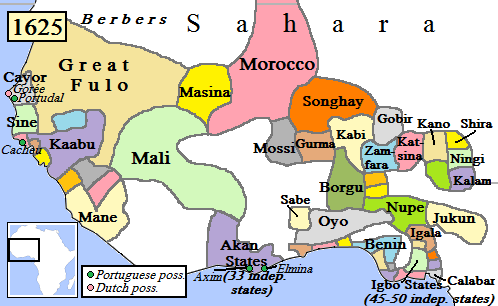

The captivating history of the West African kingdom of Kaabu, which flourished from the mid-1500s to the 1800s, has long been woven into the fabric of oral tradition, where griots—skilled storytellers—have kept alive the tales of its rulers and the kingdom’s remarkable legacy, awaiting the day when archaeology would unveil the truths behind these age-old narratives. This kingdom, at its zenith, encompassed regions that are now part of Guinea-Bissau, Senegal, and Gambia.

The stories of Kaabu were often passed down from generation to generation, sometimes from father to son, but more frequently through griots—West African oral historians renowned for their songs about the kingdom’s rulers. Nino Galissa, a musician and direct descendant of the griots who once performed for Kaabu’s last emperor, encapsulates this connection in a recent song inspired by archaeological discoveries at Kansala, the former capital of the kingdom.

“The griots have already sung it, but now we know it’s real,” Galissa reflects, highlighting the significance of the archaeological findings. These discoveries were part of a project led by the Spanish National Research Council, with Galissa’s song serving as a bridge between the past and present, effectively communicating the findings to the local community.

In Kansala, griots have historically played a crucial role in imparting history, often accompanied by the kora, a string instrument that resembles both a harp and a guitar. Antonio Queba Banjai, a descendant of Kaabu’s last emperors and president of the NGO Guinea-Lanta, emphasizes the importance of griots in African history. “They are the puzzle you cannot miss,” he states, underscoring how their narratives have shaped the understanding of his heritage.

📣 Our WhatsApp channel is now LIVE! Stay up-to-date with the latest news and updates, just click here to follow us on WhatsApp and never miss a thing!!

The archaeological team recognized the need to integrate oral history into their research, marking this as the largest archaeological dig ever conducted in Guinea-Bissau. Sirio Canos-Donnay, a leading researcher, expressed hope that this collaboration would demonstrate the value of local historical narratives alongside academic approaches. “We should respect local ways of producing and consuming history,” she noted, emphasizing the extraordinary insights that can arise from such interdisciplinary dialogue.

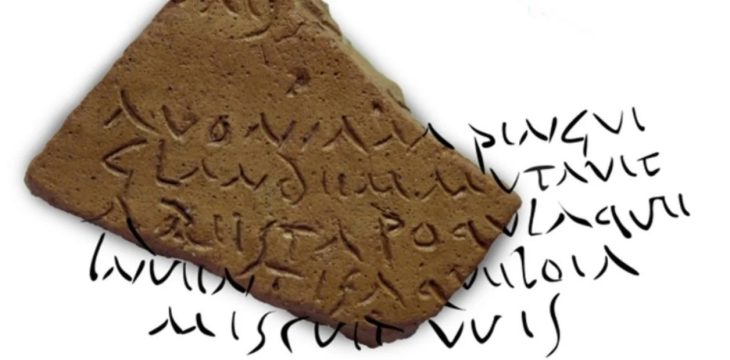

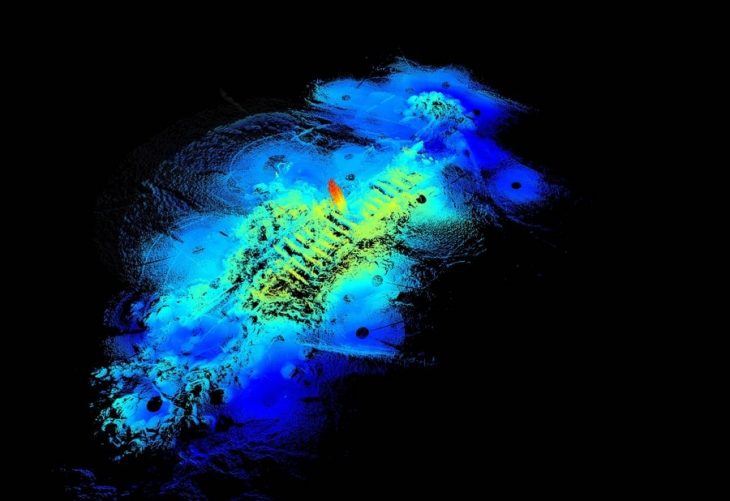

The excavation not only validated many events chronicled by griots but also revealed significant aspects of Kaabu’s history, including its dramatic downfall in the 1860s. According to legend, during a siege, the local king ignited a gunpowder store, leading to the destruction of the town. This event was corroborated by the archaeological evidence found at the site.

Additionally, the dig uncovered artifacts indicating extensive trade with Europeans, such as Venetian beads and Dutch gin, further enriching the historical narrative of Kaabu. Joao Paulo Pinto, former director of Guinea-Bissau’s National Institute of Study and Research, advocates for the recognition of West African oral history as a legitimate form of historical documentation, comparable to written records.

Banjai hopes that this project will shed light on the often-overlooked histories of West African kingdoms, ensuring that future generations appreciate their rich heritage. Through the fusion of archaeology and oral tradition, the story of Kaabu continues to resonate, bridging the past with the present.

Cover Image Credit: Nino Galissa, a seventh-generation griot – or oral historian – composed the musical version of the Kansala 2024 excavation report. Here, he plays a traditional instrument known as a kora at his home in Bissau, Guinea-Bissau. Credit: Ricci Shryock/VOA