Archaeologists have unearthed the earliest known evidence of body perforation in skeletons dating back 11,000 years at the Boncuklu Tarla excavation site in southeastern Türkiye.

Furthermore, analysis reveals that only adults had body piercings, indicating that the prehistoric custom might have been a ritual associated with coming-of-age ritual.

The findings, which date back to around 11,000 BC, shed new light on early sedentary communities’ body modification practices and call into question existing narratives about their origins in South-west Asia.

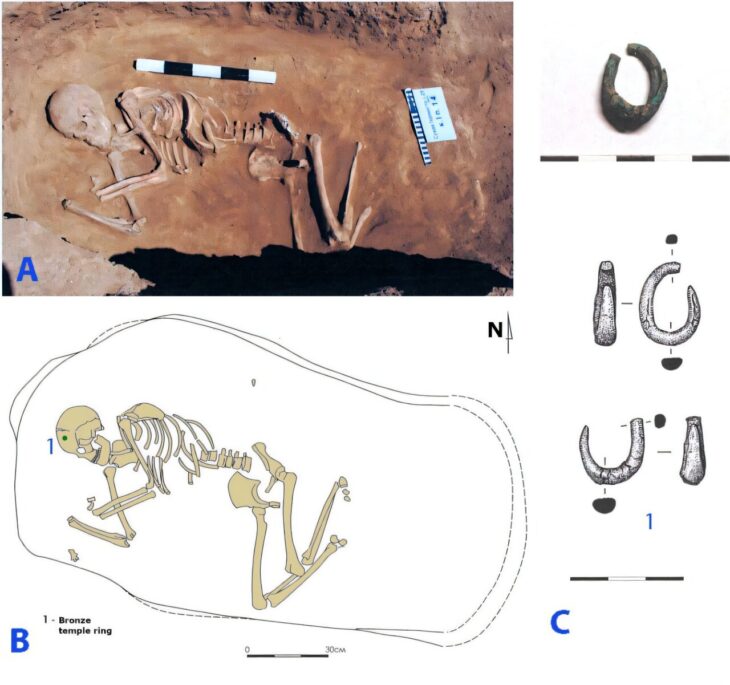

A team from Ankara University unearthed more than 100 ornaments buried in the graves of 11 thousand-year-old individuals during excavations carried out in Boncuklu Tarla between 2012 and 2017.

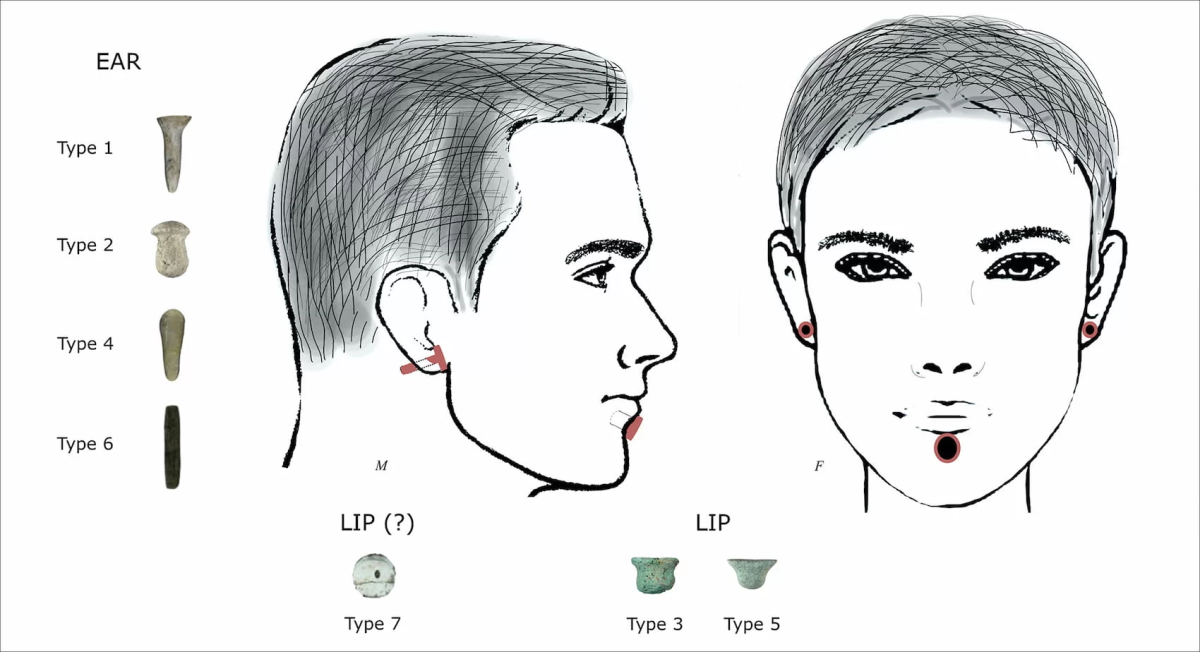

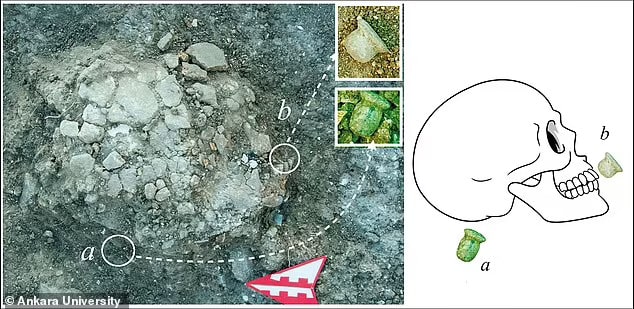

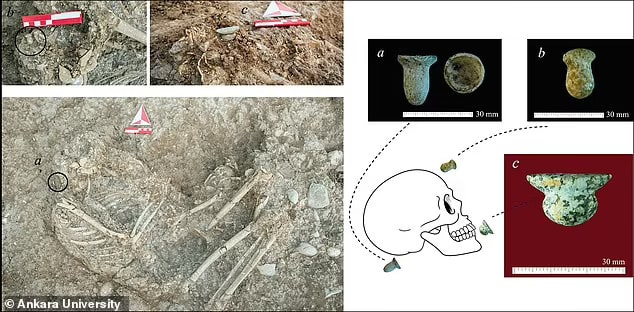

The ornaments were discovered in situ next to the ears and chins of the skeletal remains, and are mostly made from limestone, obsidian, chlorite, copper, or river pebbles. The variety of the ornaments suggests that they were designed for use in both ear and lower lip piercings known as labrets.

📣 Our WhatsApp channel is now LIVE! Stay up-to-date with the latest news and updates, just click here to follow us on WhatsApp and never miss a thing!!

This is corroborated by a skeletal analysis of the remains, which shows wear patterns on the lower incisors that match examples of labret wear in various cultures both historically and currently.

Further examination revealed that both males and females had piercings, but they were only worn by adults. None of the child burials at the site contained any evidence of these ornaments.

This suggests that piercings were not only aesthetic but also had social significance, the researchers said, adding that they are likely to have acted as a rite of passage, signifying a person reaching maturity.

Emma Louise Baysal, Associate Professor of Prehistory at Ankara University, a leading expert on Neolithic personal ornamentation, emphasizes the significance of these findings: The discovery of labrets and ear ornaments in situ at Boncuklu Tarla provides the earliest contextual evidence for the use of body augmentation requiring perforation of bodily tissue in South-west Asia. This challenges existing narratives that place initial engagement with body perforation practices around the middle of the seventh millennium BC.

These discoveries provide the first indication as to the purpose for which the earliest piercings were made and worn.

Labrets and ear ornaments were widely used in parts of southwest Asia during the early Neolithic period. Although some examples have been found in western Anatolia and the Aegean, there is no evidence for their use in the neolithic regions of central Anatolia.

The research team at Boncuklu Tarla, led by Dr Emma Louise Baysal, believes that this discovery will help clarify the terminology surrounding these artifacts and pave the way for a re-evaluation of existing South-West Asian Neolithic data.

Dr. Baysal said: ‘It shows that traditions that are still very much part of our lives today were already developed at the important transitional time when people first started to settle in permanent villages in western Asia more than 10,000 years ago.’

‘They had very complex ornamentation practices involving beads, bracelets, and pendants, including a very highly developed symbolic world which was all expressed through the medium of the human body,’ Dr Baysal added.

Researchers hope to learn more about the choices made regarding raw materials and the connections between general ornamentation activities and traditions of corporal ornamentation as they continue their excavations at Boncuklu Tarla.

The findings were published in the journal Antiquity.

https://doi.org/10.15184/aqy.2024.28

Cover Image: Illustration of the hypothetical use of labrets and ear ornaments found at Boncuklu Tarla. Credit: Ergül Kodaş, Emma L Baysal et al. / Antiquity