A multidisciplinary team combined archaeology, DNA, and isotopic science to reveal the human toll of Rome’s “Crisis of the Third Century.”

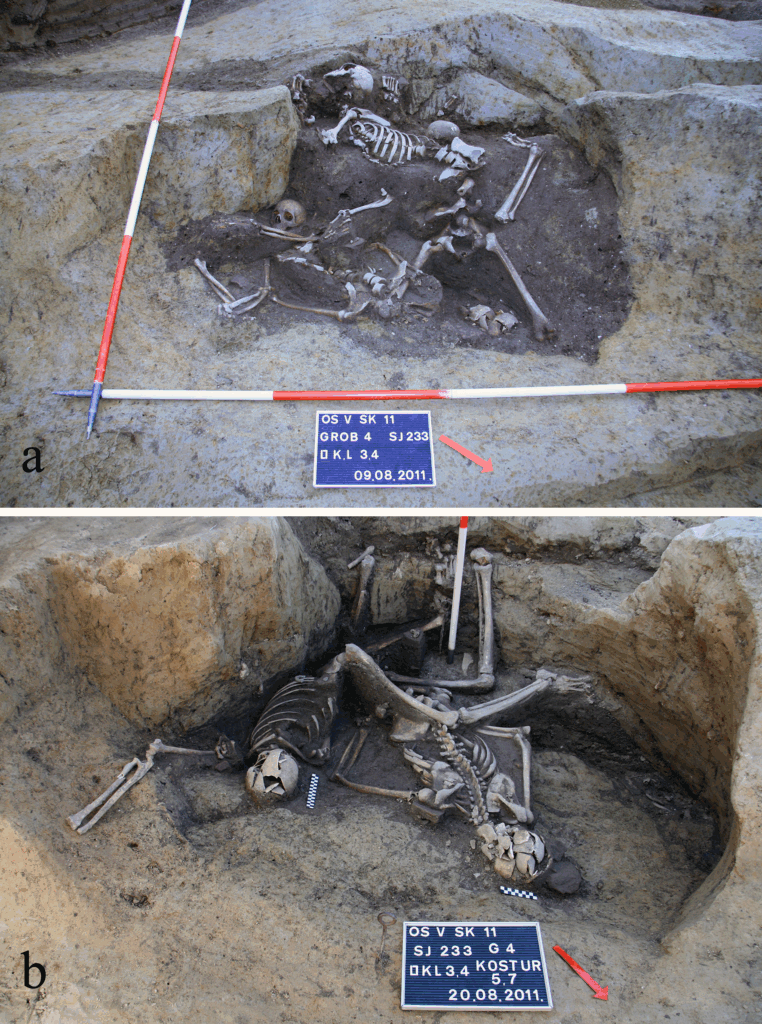

When archaeologists first peered into an abandoned Roman well in the Croatian city of Osijek, they did not expect to find the silent witnesses of a forgotten battlefield. Inside the dark shaft lay seven complete human skeletons—men who died nearly 1,700 years ago. Now, a new study published in PLOS ONE sheds light on their identity, suggesting that these men were Roman soldiers killed during one of the Empire’s most chaotic chapters: the mid-third century CE.

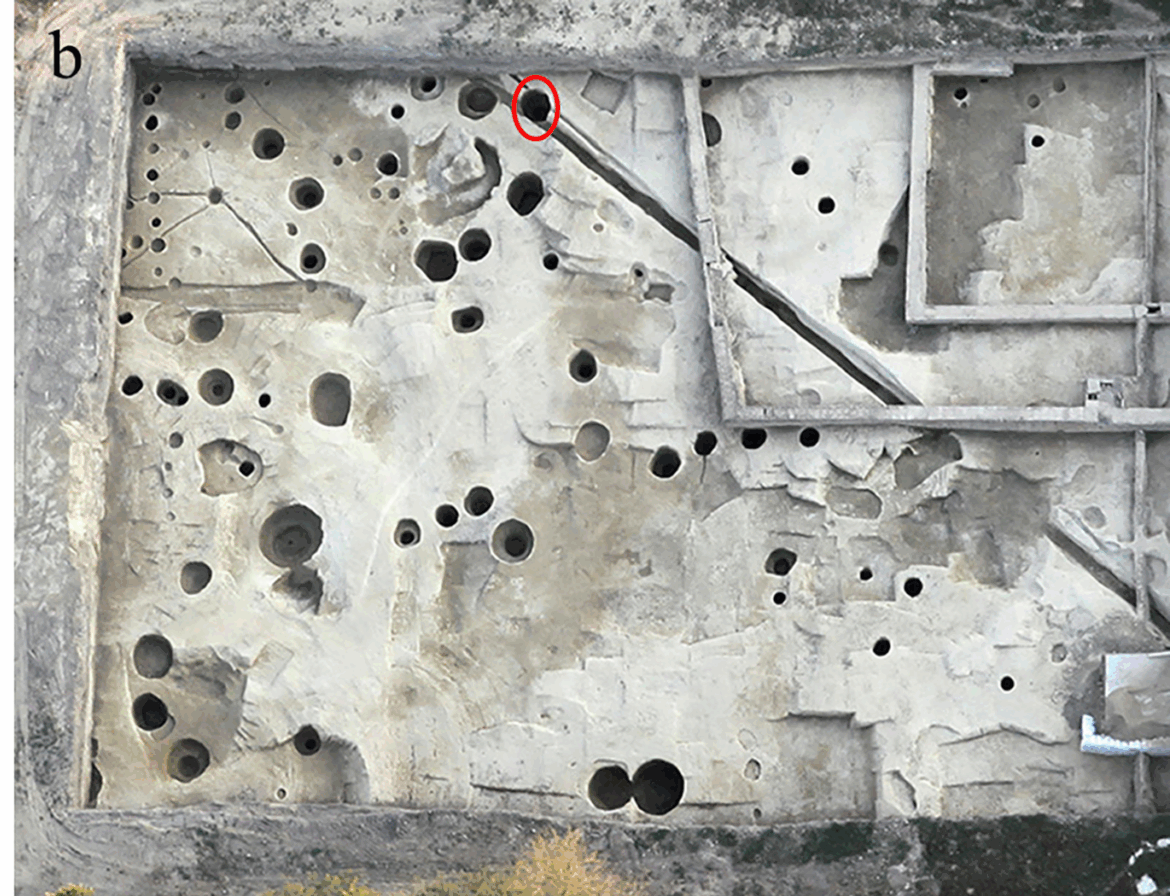

The discovery, made during excavations in 2011 at the site of the ancient Roman city of Mursa (modern-day Osijek), has since become one of the most striking archaeological finds from the Roman Balkans. Through a combination of radiocarbon dating, isotopic chemistry, and ancient DNA sequencing, researchers from Croatia, Germany, and Slovenia pieced together the story of the seven men whose final resting place was a disused water well.

A Death in the Time of Crisis

Radiocarbon dating places the burial between 240 and 340 CE, coinciding with the Crisis of the Third Century—a 50-year period of political instability, civil war, and foreign invasion that nearly tore the Roman Empire apart. Historical accounts describe two major battles fought near Mursa, including the clash between Emperor Gallienus and the usurper Ingenuus around 260 CE.

“Everything points to a single catastrophic event,” says Dr. Mario Novak, lead author from the Institute for Anthropological Research in Zagreb. “The seven men appear to have been buried—or more likely, dumped—into the well shortly after death, still fully fleshed, suggesting a mass disposal after battle.”

📣 Our WhatsApp channel is now LIVE! Stay up-to-date with the latest news and updates, just click here to follow us on WhatsApp and never miss a thing!!

Archaeological evidence supports this. The skeletons were found fully articulated, one atop another, implying a rapid, single deposition rather than a series of burials. A coin minted in 251 CE under Emperor Hostilian found nearby confirmed the mid-third-century timeline.

Lives of Soldiers, Deaths of Violence

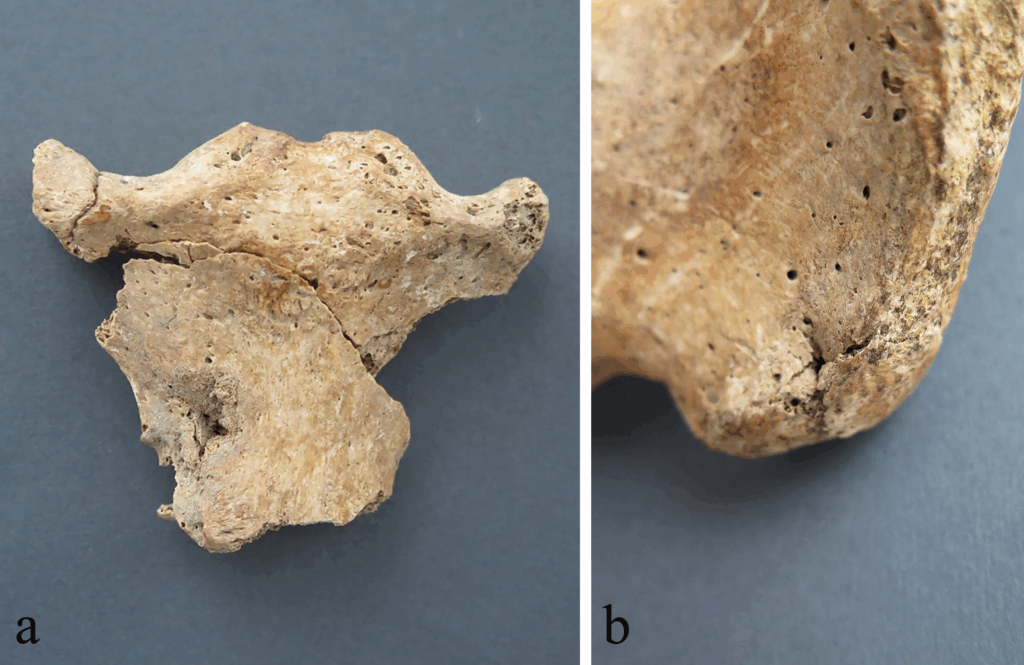

Bioarchaeological analysis revealed that all seven were adult males, aged between 18 and 50, with an average height of 172.5 cm—taller and more robust than typical civilians of the era. Their bones told stories of hardship and combat: healed fractures, muscle stress markers, and spine damage consistent with years of physical strain.

Several individuals bore clear signs of combat trauma. One man had a puncture wound through the chest bone, likely from a spear or arrow. Another showed a sword cut to the arm and rib, while a third bore healed blunt-force injuries to the skull. These were not victims of plague or famine, but men who had lived—and died—by the sword.

“The demographic profile matches that of Roman legionaries,” Novak explains. “They were young, strong, and highly active individuals who likely fought in organized military units.”

What They Ate—and Where They Came From

To further understand their lives, scientists extracted collagen from the men’s ribs to analyze carbon and nitrogen isotopes. The results pointed to a mixed C3/C4 plant-based diet, dominated by grains like wheat and millet, with limited meat and almost no seafood—remarkably similar to historical records of Roman military rations.

Ancient DNA (aDNA) provided even more striking insights. Four of the skeletons yielded enough genetic material for sequencing, revealing a surprising genetic diversity. Unlike the local Iron Age population, none of the men shared regional ancestry. Instead, their genetic profiles traced to Northern Europe, the Eastern Mediterranean, and the Pontic-Caspian steppes.

“This level of genetic heterogeneity reflects the Roman army’s diversity,” says Dr. Cosimo Posth of the University of Tübingen, a co-author of the study. “The Empire recruited soldiers from across Europe and beyond, and this mass grave captures that diversity in a single moment of crisis.”

Science Illuminates a Forgotten War

The combination of isotopic, genomic, and archaeological evidence paints a vivid picture: seven soldiers from different corners of the Empire, united in service, perished together in the Battle of Mursa—one of the bloodiest yet least understood conflicts of Roman history.

While ancient sources offer little detail about the 260 CE battle, they do mention massive casualties. The victors likely showed little mercy; the losers may have been executed or left unburied. For centuries, the traces of that violence lay hidden beneath the streets of modern Osijek.

“This find doesn’t just tell us how these men died,” Novak says. “It tells us how far the reach of Rome extended, how interconnected its people were, and how devastating the empire’s internal conflicts could be.”

A Well of History

The Mursa mass grave stands as a microcosm of the Roman Empire itself—multicultural, militarized, and ultimately fragile under the weight of its own ambitions. Each skeleton offers a data point in a growing scientific effort to reconstruct the lived experiences of ancient soldiers.

By merging archaeology with genomics, scientists can now move beyond artifacts and inscriptions to explore the biographies of the dead—where they came from, what they ate, and how they met their end.

As the study concludes, “The multidisciplinary analysis of the Mursa mass grave reveals the human cost of Rome’s third-century turmoil, preserved for millennia in the silence of a well.”

Novak M, Yavuz OE, Carić M, Filipović S, Posth C (2025) Multidisciplinary study of human remains from the 3rd century mass grave in the Roman city of Mursa, Croatia. PLoS One 20(10): e0333440. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0333440

Cover Image Credit: The exact location of the well SU 233/234 during the excavation (in red circle). Credit: PLoS One (2025)