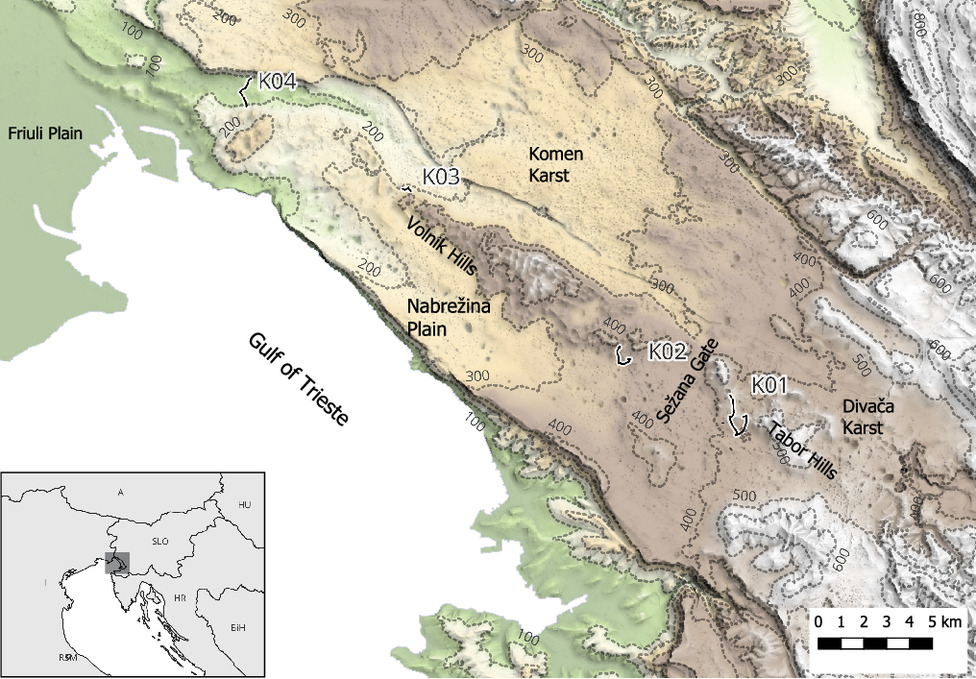

In a stunning discovery that reshapes our understanding of prehistoric Europe, archaeologists have uncovered monumental stone hunting megastructures hidden in the Adriatic hinterland of Slovenia and Italy. These vast constructions—spanning several kilometers across the rugged Karst Plateau—represent the first known evidence of large-scale, purpose-built hunting architecture in Europe.

Revealed through advanced airborne laser scanning (LiDAR), the newly identified sites consist of funnel-shaped stone alignments leading into concealed enclosures, apparently designed to guide and trap herds of wild animals such as red deer. Their architectural sophistication, monumental scale, and integration with the natural terrain suggest a high level of communal planning, coordination, and environmental knowledge among prehistoric builders thousands of years ago.

Published in PNAS (Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, October 2025), the research—led by Dimitrij Mlekuž Vrhovnik and Tomaž Fabec—positions these structures as the westernmost examples of a hunting tradition previously known only from the deserts of Southwest Asia and North Africa, where so-called “desert kites” were used to capture gazelles and other game. Their discovery in temperate Europe challenges long-standing assumptions about prehistoric subsistence, technology, and social organization.

Europe’s First “Desert Kites”

Until now, such sophisticated mass-hunting systems—known as desert kites—were thought to exist only in Southwest Asia and North Africa, where stone alignments stretching for kilometers guided gazelles and antelopes into traps.

“The Karst Plateau structures show striking architectural and functional similarities to the desert kites of Jordan, Syria, and the Negev,” the authors write. “They extend the known range of these megastructures into temperate Europe for the first time.”

📣 Our WhatsApp channel is now LIVE! Stay up-to-date with the latest news and updates, just click here to follow us on WhatsApp and never miss a thing!!

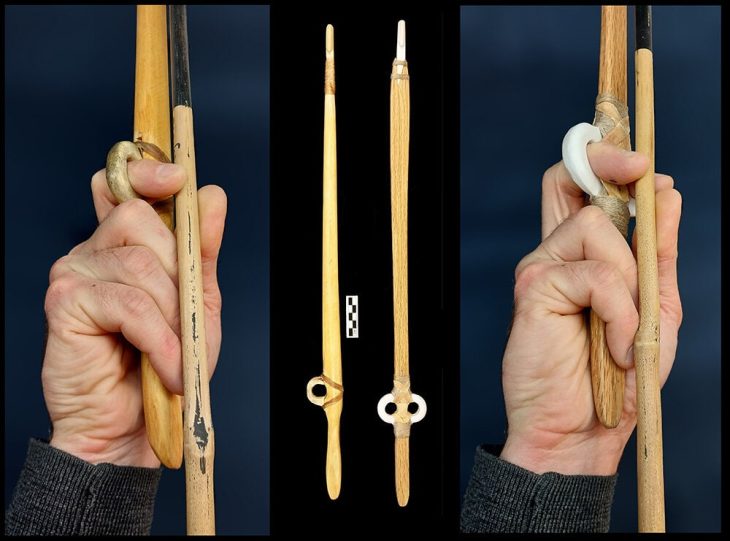

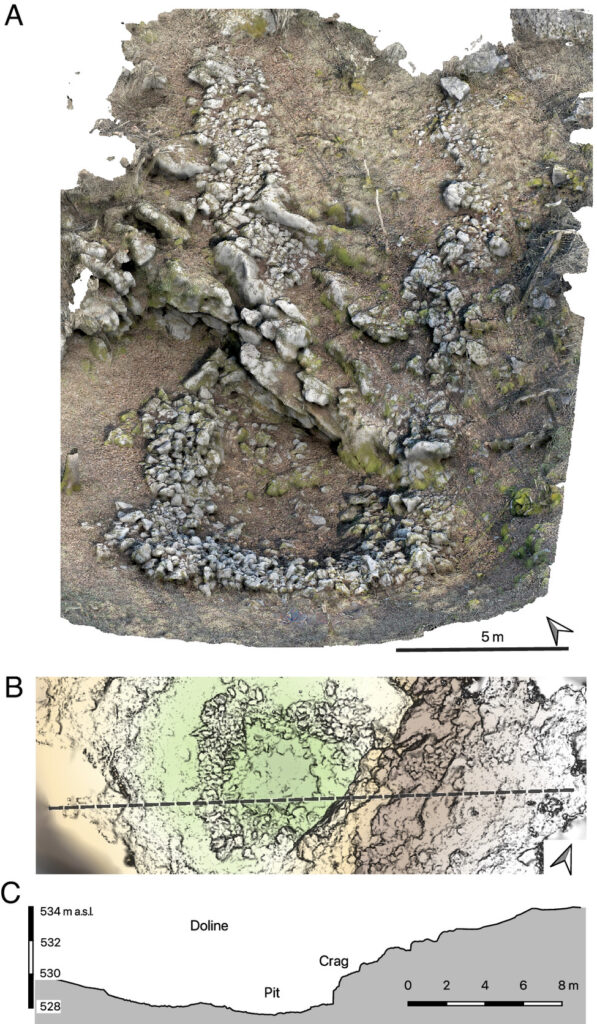

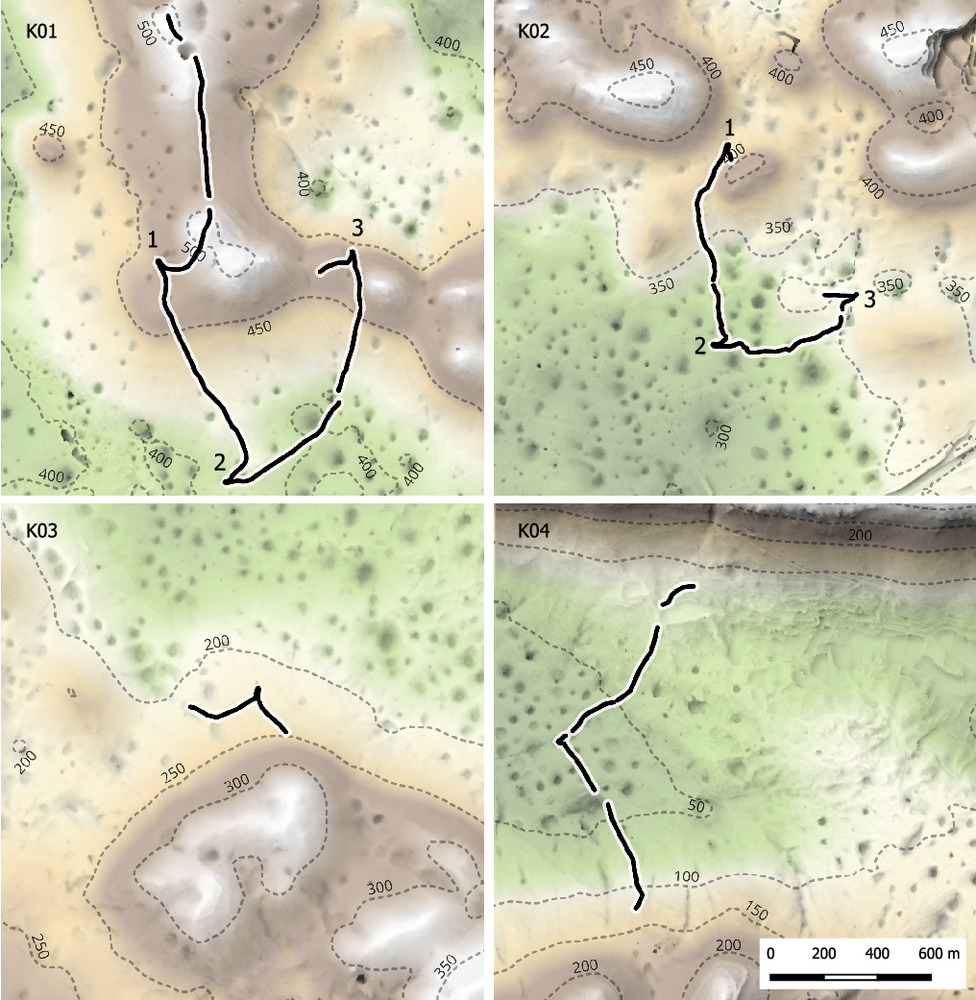

Each installation includes two long, low walls, some more than 3.5 kilometers in length, converging toward a deep pit or enclosure built into a doline—a natural sinkhole—often beneath a cliff or rock ledge. The result was an ingenious natural-architectural funnel: animals driven along the corridor would find themselves trapped in a steep, enclosed space with no escape.

Laser Scans Reveal Hidden Giants

The discovery was possible thanks to high-resolution LiDAR (light detection and ranging) technology, which can penetrate dense vegetation to expose ancient topography. The team mapped over 870 square kilometers of the Karst region, revealing the massive stone alignments preserved for millennia.

While some of the walls remain only half a meter tall today, their layout, scale, and integration with terrain suggest careful planning and coordinated community labor. The largest site, dubbed K01, required an estimated 5,000 hours of collective work and more than 3,000 cubic meters of stone—a feat comparable to early monumental construction elsewhere in the prehistoric world.

“These were not random piles of rock,” says Mlekuž Vrhovnik. “They represent a shared vision—engineering on a landscape scale—built by communities who understood animal movement and topography intimately.”

Ancient Engineers of the European Wilds

Radiocarbon dating from charcoal found inside one of the pits suggests the structures were abandoned before the Late Bronze Age, possibly originating much earlier—perhaps during the Mesolithic or Early Neolithic period (over 6,000 years ago).

At that time, red deer dominated hunting economies in the region. Sites such as Grotta dell’Edera and Pupićina Cave show intensive red deer exploitation, consistent with cooperative, seasonal hunts. These large-scale events may have supplied food surpluses, reinforced community ties, or even fueled ritual feasts celebrating successful drives.

If so, the Karst structures could represent the largest and most complex hunting system ever identified in prehistoric Europe—a remarkable testament to communal organization long before the rise of cities or states.

Built for the Hunt, Not for Herding

While some stone enclosures elsewhere have been linked to early pastoralism, the Adriatic traps’ hidden, cliff-edge locations make them impractical for livestock. Their design—concealed endpoints, steep drops, and visually guided approach routes—matches hunting logic, not animal management.

Visibility analyses show that the final pit remains invisible until the last 20 meters of approach, suggesting hunters could surprise animals at the final moment. The structures exploit natural ridges, valleys, and saddles, shaping the animals’ path through both architecture and terrain.

“The builders understood how to manipulate movement, light, and perspective,” notes Fabec. “They designed landscapes of deception.”

A Challenge to Old Narratives

The implications are profound. Archaeologists have long assumed that large-scale, organized hunting architecture was unique to the arid zones of the Middle East. This new evidence from Slovenia challenges that view, suggesting that European prehistoric societies were equally capable of complex planning and cooperative engineering.

It also highlights the sophisticated environmental knowledge of early communities who could read the landscape, predict animal behavior, and mobilize labor to reshape entire ecosystems for collective survival.

“These findings rewrite what we thought we knew about prehistoric Europe,” says Mlekuž Vrhovnik. “They show that monumental architecture did not begin with temples or tombs—it began with the hunt.”

Reconstructing Forgotten Landscapes

The research contributes to a growing recognition that prehistoric peoples were landscape architects as much as hunters. The Karst Plateau’s stony terrain, riddled with dolines and escarpments, preserved these traces remarkably well.

By combining LiDAR data, excavation, GIS modeling, and environmental analysis, the team paints a vivid picture of cooperative hunting societies thriving in Europe’s early Holocene landscapes—communities that could coordinate labor, design large-scale traps, and manage resources collectively.

Whether these structures date to the Mesolithic foragers or the early Bronze Age herders, they demonstrate a shared capacity for collective vision, technological innovation, and ecological adaptation—qualities that echo across human history.

A New Chapter in Prehistoric Europe

The Karst hunting megastructures stand as silent witnesses to a forgotten era—when early Europeans turned stone and landscape into tools of survival.

Their rediscovery opens a new frontier in archaeology, linking Europe’s deep past with global traditions of mass hunting and monumental construction.

As the study concludes: “These installations expose the prehistoric coupling of animal ecology with architectural foresight—transforming the natural world into infrastructure.”

From the windswept ridges above the Adriatic, the ancient hunters’ design still endures—etched into the rock, hidden beneath forests, waiting thousands of years to tell its story.

Mlekuž Vrhovnik, D., & Fabec, T. (2025). Prehistoric hunting megastructures in the Adriatic hinterland. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 122(42), e2511908122. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2511908122

Cover Image Credit: Location of the study area in the northern Adriatic hinterland, showing the four funnel-shaped stone structures identified on the Karst Plateau. The map highlights key landscape features connecting the Gulf of Trieste with the interior. Mlekuž Vrhovnik & Fabec, 2025.