A small Roman glass vessel excavated in the ancient city of Pergamon has delivered the first direct chemical evidence that feces-based remedies described in Greco-Roman medical texts were not merely theoretical, but actively prepared and used in antiquity.

The findings come from an interdisciplinary study combining archaeochemical analysis with historical and philological research, offering a rare material confirmation of practices long known only from ancient authors. At the center of the discovery is an unassuming glass unguentarium—traditionally interpreted as a container for perfumes or cosmetic oils—that instead appears to have held a deliberately formulated medicinal mixture.

A Medical Center Yields an Unexpected Answer

Pergamon was one of the most important centers of medicine in the Roman world, closely associated with the cult of Asclepius and with prominent physicians active during the Imperial period. Yet despite the city’s medical reputation, direct archaeological evidence for many treatments described in ancient texts has remained elusive—particularly remedies involving substances considered socially or sensorially problematic.

The vessel examined in the study, catalogued as inventory number 4027 and now housed in the Bergama Archaeology Museum, dates to the second century CE. Its form belongs to a widely distributed type of Roman glass unguentarium, commonly assumed to have held scented oils or cosmetics. Until now, little attention had been paid to the possibility that such containers might also have transported medicinal compounds with more complex or controversial ingredients.

Chemical Analysis Reveals Human Fecal Biomarkers

To test this possibility, researchers conducted a detailed residue analysis using gas chromatography combined with mass spectrometry and flame ionization detection (GC–MS/FID). Samples were carefully collected from the neck and base of the vessel, yielding approximately 14.6 grams of dark, compact organic material.

📣 Our WhatsApp channel is now LIVE! Stay up-to-date with the latest news and updates, just click here to follow us on WhatsApp and never miss a thing!!

The chemical results were unambiguous. Two compounds—coprostanol and 24-ethylcoprostanol—were identified in a ratio that strongly indicates human fecal matter. These sterols are produced by microbial activity in the human gut and are widely recognized as reliable biomarkers for human excrement. Their presence, combined with rigorous contamination controls, ruled out accidental intrusion or later pollution.

This marks the first time that human fecal matter has been chemically identified inside a Roman medicinal container.

Odor Was Not an Accident—It Was Managed

Equally significant was the identification of carvacrol, an aromatic compound found in thyme and related plants native to Anatolia. This detail proved crucial for interpreting the find, as it closely mirrors prescriptions found in ancient medical literature.

Classical authors such as Galen, Dioscorides, and Pliny the Elder repeatedly described the medicinal use of animal—and occasionally human—excrement. These texts also show a clear awareness of the sensory challenges such remedies posed. Physicians frequently recommended mixing dung-based ingredients with aromatic herbs, wine, vinegar, or oils to suppress odor and improve patient compliance.

The chemical pairing of fecal biomarkers with thyme-derived compounds inside unguentarium 4027 provides the first material proof that these textual instructions were actively followed. This was not waste matter sealed by chance, but a deliberately prepared medicinal substance whose unpleasant qualities were carefully managed.

Rethinking the Role of Roman Unguentaria

The discovery forces a reassessment of how archaeologists interpret small glass vessels from Roman contexts. Unguentaria have long been classified almost exclusively as cosmetic containers, reinforcing a modern distinction between medicine and personal care that did not necessarily exist in antiquity.

Ancient medical practice routinely blurred the boundaries between healing, hygiene, ritual, and social acceptability. Ointments could serve therapeutic, cosmetic, and symbolic functions simultaneously. The Pergamon unguentarium suggests that these vessels may have played a key role in transporting and administering medicines that required careful sensory mediation.

In this sense, the container itself becomes part of the therapy—not just a neutral object, but a socially managed interface between physician, substance, and patient.

From Ancient Remedies to Modern Parallels

While the idea of feces-based medicine may appear unsettling today, the study draws a cautious parallel with modern medical practices. Fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT), now used to treat certain gastrointestinal disorders, similarly relies on the therapeutic potential of human gut material—albeit grounded in microbiological science rather than humoral theory.

The researchers emphasize that ancient physicians lacked any concept of microbes. Nonetheless, the continuity in recognizing fecal matter as a source of healing power invites a broader reconsideration of practices long dismissed as irrational or marginal. Within their historical and cultural frameworks, these treatments formed part of a coherent medical logic.

Material Proof Changes the Narrative

Until now, feces-based therapeutics in Roman medicine rested entirely on textual testimony. The Pergamon unguentarium changes that balance. By providing molecular-level evidence of human excrement intentionally combined with aromatic agents, the study confirms that such remedies were not hypothetical constructs, but physically prepared and circulated substances.

More broadly, the research demonstrates the value of integrating chemical analysis with historical scholarship. Together, these approaches reveal not only what ancient people wrote about medicine, but what they actually made, stored, and used.

In doing so, a modest glass vessel from Roman Pergamon has opened an unexpectedly concrete window onto the sensory, social, and therapeutic realities of ancient healthcare—adding a tangible chapter to the long and complex history of medicine.

Atila, C., Demirbolat, İ., & Babaç Çelebi, R. (2026). Feces, fragrance and medicine: Chemical evidence of ancient therapeutics in a Roman unguentarium. Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports

Volume 70, April 2026, 105589. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jasrep.2026.105589

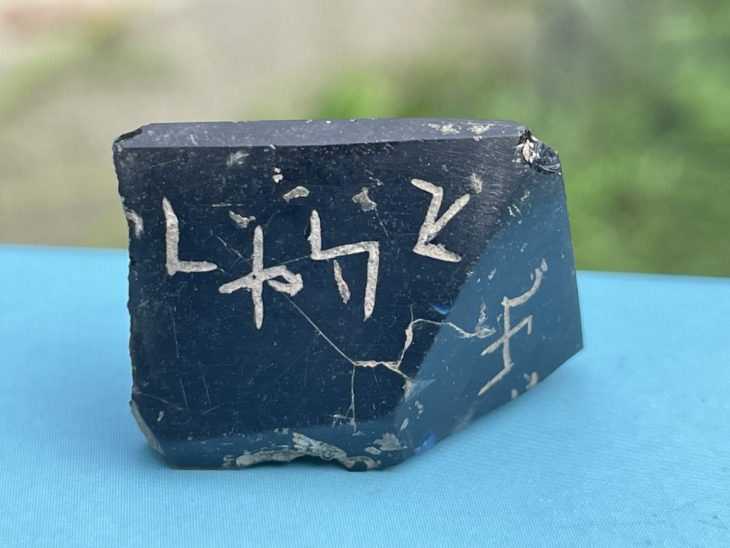

Cover Image Credit: Roman unguentaria, typically interpreted as cosmetic containers, were small glass vessels used to store scented oils, ointments, and, as new evidence suggests, medically prepared substances. Antiguarian