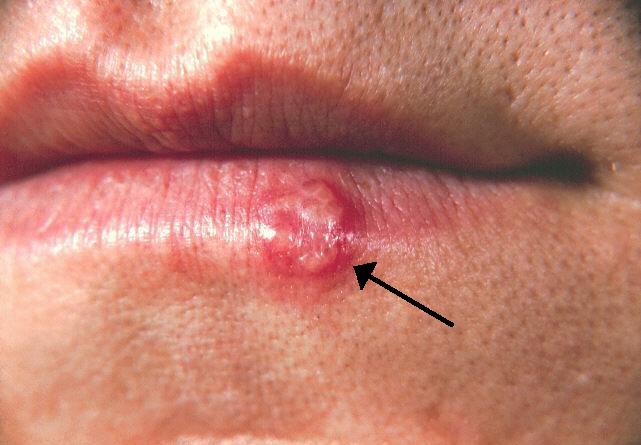

The ancient genomes of the herpes virus, which commonly causes lip sores and currently infects about 3.7 billion people worldwide, have been uncovered and sequenced for the first time by Cambridge University researchers.

However, despite its prevalence, little is known about the origins of this virus or how it spread over the globe. As a result, an international team of experts screened the DNA of teeth from hundreds of people found at ancient archaeological sites.

According to recent research, the HSV-1 virus strain that causes face herpes as we know it today first appeared some 5,000 years ago, following massive Bronze Age migrations into Europe from the Steppe grasslands of Eurasia and the ensuing population booms that accelerated transmission rates.

Herpes has been around for millions of years, and different strains of the virus infect everything from bats to coral. Despite its current prevalence in humans, experts say that ancient examples of HSV-1 were unexpectedly difficult to discover.

According to the study’s authors, the emergence of a new cultural activity brought from the east—romantic and sexual kissing—may have corresponded with the Neolithic flourishing of facial herpes observed in the ancient DNA.

📣 Our WhatsApp channel is now LIVE! Stay up-to-date with the latest news and updates, just click here to follow us on WhatsApp and never miss a thing!!

Researchers found four people who had the virus when they died. They extracted viral DNA from the roots of the teeth of the infected individuals. Herpes often flares during mouth infections and these ancient cadavers included two people with gum disease and one who smoked tobacco.

The individuals lived at various times over a thousand-year period. They included an adult male excavated in Russia’s Ural Mountain region. He lived during the Iron Age, about 1,500 years ago.

Another two samples were found near Cambridge. They were a female from an early Anglo-Saxon cemetery a few miles south of the city, dating from the 6th to the 7th centuries. The other was a young adult male from the late 14th century. He was buried in the grounds of medieval Cambridge’s charitable hospital and had suffered what researchers called “appalling” dental abscesses.

The fourth sample was from a young adult male excavated in Holland. They were able to surmise he had been a fervent clay pipe smoker, most likely massacred by a French attack on his village by the banks of the Rhine in 1672.

“By comparing ancient DNA with herpes samples from the 20th century, we were able to analyze the differences and estimate a mutation rate and, consequently, a timeline for virus evolution,” said co-lead study author Dr. Lucy van Dorp, from University College London’s Genetics Institute.

According to co-senior study author Dr. Christiana Scheib, “Every primate species has a form of herpes, so we assume it has been with us since our own species left Africa.” Scheib is a research fellow at St. John’s College, University of Cambridge, and head of the Ancient DNA lab at the University of Tartu.

“However, something happened around 5,000 years ago that allowed one strain of herpes to overtake all others, possibly an increase in transmissions, which could have been linked to kissing,” Scheib noted.

“Only genetic samples that are hundreds or even thousands of years old will allow us to understand how DNA viruses such as herpes and monkeypox, as well as our own immune systems, are adapting in response to each other,” said co-senior study author Dr. Charlotte Houldcroft, from the department of genetics at the University of Cambridge, in England.

The team would like to trace this hardy primordial disease even deeper through time, to investigate its infection of early hominins. “Neanderthal herpes is my next mountain to climb,” added Scheib.

The findings were published July 27 in the journal Science Advances.

Cover Photo: Dr Barbara Veselka