The genomic history of the Balkan Peninsula during the first millennium of the common era—a period marked by significant changes in language, culture, and population—has been reconstructed through a multidisciplinary study.

The team has recovered and analyzed whole genome data from 146 ancient people excavated primarily from Serbia and Croatia—more than a third of which came from the Roman military frontier at the massive archaeological site of Viminacium in Serbia—which they co-analyzed with data from the rest of the Balkans and nearby regions.

Iñigo Olalde, Ikerbasque Research Fellow at the University of the Basque Country (UPV/EHU) and Ramón y Cajal Researcher has, together with the Institute of Evolutionary Biology (IBE: CSIC-UPF), and Harvard University, led a study in which they have, for the first time, reconstructed the genomic history of the first millennium of the Balkan Peninsula.

The work, published in the prestigious journal Cell, depicts the Balkans as a global, cosmopolitan frontier of the Roman Empire and reconstructs the arrival of Slavic peoples in this region.

“Archaeogenetics is an indispensable complement to archaeological and historical evidence. A new and much richer picture comes into view when we synthesize written records, archaeological remains like grave goods and human skeletons, and ancient genomes”, said co-author Kyle Harper, a historian of the ancient Roman world at the University of Oklahoma.

📣 Our WhatsApp channel is now LIVE! Stay up-to-date with the latest news and updates, just click here to follow us on WhatsApp and never miss a thing!!

The Roman Empire transformed the Balkans into a global region

First, the Roman Republic and then the Roman Empire incorporated the Balkans and turned this border region into a crossroads of communications and a melting pot of cultures.

After Rome occupied the Balkans, it turned this border region into a crossroads, one that would eventually give rise to 26 Roman Emperors, including Constantine the Great, who shifted the capital of the empire to the eastern Balkans when he founded the city of Constantinople.

The team’s analysis of ancient DNA shows that during the period of Roman control, there was a large demographic contribution of people of Anatolian descent that left a long-term genetic imprint in the Balkans. This ancestry shift is very similar to what a previous study showed happened in the megacity of Rome itself—the original core of the empire—but it is remarkable that this also occurred at the Roman Empire’s periphery.

A particular surprise is that there is no evidence of a genetic impact on the Balkans of migrants of Italic descent: “During the Imperial period, we detect an influx of Anatolian ancestry in the Balkans and not that of populations descending from the people of Italy,” said Íñigo Olalde, Ikerbasque researcher at the University of the Basque Country and co-lead author of the study. “These Anatolians were intensively integrated into local society. At Viminacium, for example, there is an exceptionally rich sarcophagus in which we find a man of local descent and a woman of Anatolian descent buried together.”

The team also discovered cases of sporadic long-distance mobility from far-away regions, such as an adolescent boy whose ancestral genetic signature most closely matches the region of Sudan in sub-Saharan Africa and whose childhood diet was very different from the rest of the individuals analyzed. He died in the 2nd century CE and was buried with an oil lamp representing an iconography of the eagle related to Jupiter, one of the most important gods for the Romans.

“We don’t know if he was a soldier, slave or merchant, but the genetic analysis of his burial reveals that he probably spent his early years in the region of present-day Sudan, outside the limits of the Empire, and then followed a long journey that ended with his death at Viminacium (present-day Serbia), on the northern frontier of the Empire,” said Carles Lalueza-Fox, principal investigator at the Institute of Evolutionary Biology and director of the Museum of Natural Sciences of Barcelona.

The Roman Empire welcomed barbarian populations long before its fall

The study identified a number of individuals of northern European and steppe ancestry who inhabited the Balkan Peninsula during the 3rd century at the height of the Roman occupation. Anthropological analysis of their skulls reveals that some of them were artificially deformed, a custom peculiar to certain populations of the steppes and the Huns, often referred to as “barbarians”.

These findings support historical and archaeological research and point to the presence of individuals from outside the borders of the Empire, beyond the Danube, long before the fall of the Western Empire. “The borders of the Empire were much more diffuse than the borders of today’s nation-states. The Danube served as a geographical boundary of the Empire but acted as a communication route and was highly permeable to the movement of people,” said Pablo Carrión, Institute of Evolutionary Biology (IBE) researcher and co-lead author of the study.

Slavic populations changed the demographic composition of the Balkans

The Roman Empire permanently lost control of the Balkans in the sixth century, and the study reveals the subsequent large-scale arrival in the Balkans of individuals genetically similar to the modern Slavic-speaking populations of Eastern Europe. Their genetic fingerprint accounts for 30-60% of the ancestry of today’s Balkan peoples, representing one of the largest permanent demographic shifts anywhere in Europe in the early medieval period.

The study is the first to detect the sporadic arrival of individual migrants who long preceded later population movements, such as a woman of Eastern European descent buried in a high imperial cemetery. Then, from the 6th century onwards, migrants from Eastern Europe are observed in larger numbers; as in Anglo-Saxon England, the population changes in this region were at the extreme high end of what occurred in Europe and were accompanied by language shifts.

“According to our ancient DNA analysis, this arrival of Slavic-speaking populations in the Balkans took place over several generations and involved entire family groups, including both men and women,” explains Pablo Carrión, a researcher at the Institute of Evolutionary Biology and co-lead author of the study.

The establishment of Slavic populations in the Balkans was greatest in the north, with a genetic contribution of 50-60% in present-day Serbia, and gradually less towards the south, with 30-40% in mainland Greece and up to 20% in the Aegean islands. “The major genetic impact of Slavic migrations is visible not only in current Balkan Slavic-speaking populations, but also in places that today do not speak Slavic languages such as Romania and Greece,” said co-senior author David Reich, professor of genetics in the Blavatnik Institute at Harvard Medical School and professor of human evolutionary biology in Harvard’s Faculty of Arts and Sciences.

Bringing together historians, archaeologists, and geneticists

The study involved an interdisciplinary collaboration of over 70 researchers, including archaeologists who excavated the sites, anthropologists, historians and geneticists.

“This work exemplifies how genomic data can be useful for getting beyond contentious debates around identity and ancestry that have been inspired by historical narratives rooted in nascent nineteenth-century nationalisms and that have contributed to conflict in the past,” Lalueza-Fox said.

The team also generated genomic data from diverse present-day Serbs that could be compared with ancient genomes and other present-day groups from the region.

“We found there was no genomic database of modern Serbs. We therefore sampled people who self-identified as Serbs on the basis of shared cultural traits, even if they lived in different countries such as Serbia, Croatia, Montenegro or North Macedonia”, said co-author Miodrag Grbic, a professor at the University of Western Ontario, Canada.

Co-analyzing the data with that of other modern people in the region, as well as the ancient individuals, shows that the genomes of the Croats and Serbs are very similar, reflecting shared heritage with similar proportions of Slavic and local Balkan ancestry.

“Ancient DNA analysis can contribute, when analyzed together with archaeological data and historical records, to a richer understanding of the history of Balkans history,” said Grbic. “The picture that emerges is not of division, but of shared history. The people of the Iron Age throughout the Balkans were similarly impacted by migration during the time of the Roman Empire and by Slavic migration later on. Together, these influences resulted in the genetic profile of the modern Balkans—regardless of national boundaries.”

University of Oklahoma

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2023.10.018

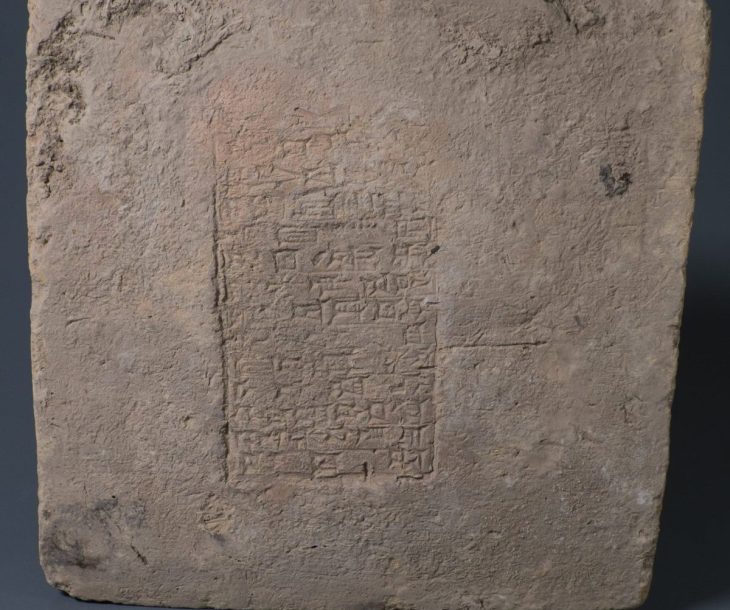

Cover Photo: Ilija Mikić.