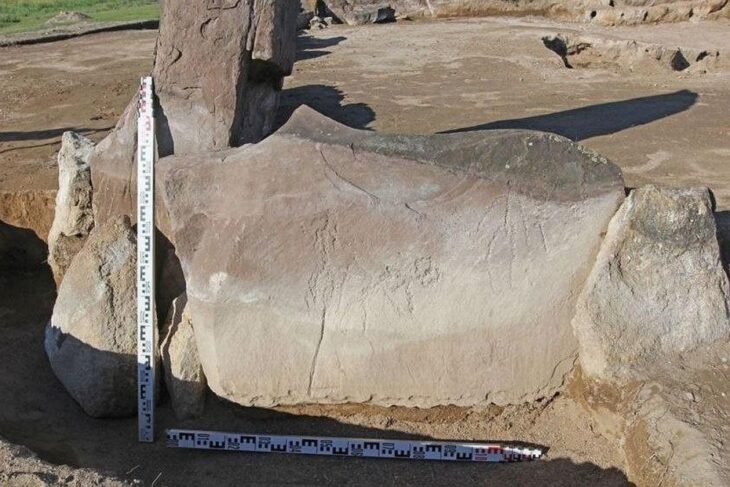

Dr. David Zhang and his team’s investigations of Quesang on the Tibetan Plateau in 2018 and 2020 sparked controversy, along with the discovery of potential parietal art.

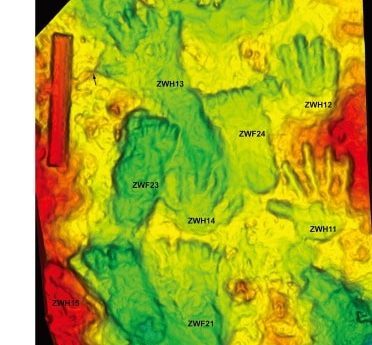

Dr. David Zhang first found hand and footprints near the hot spring bath in 1988 at the active Quesang Hot Spring near Quesang Village, about 80 km northwest of Lhasa, Tibet. Recent research conducted between 2018 and 2020 resulted in the finding of the possible parietal art.

According to Zhang’s team, whose findings were published in Science Bulletin, the tracks are between 169,000 and 226,000 years old, dating back to the Earth’s last ice age.

The use of hands as molds in cave paintings dates back to about 40,000 years ago in Sulawesi (Indonesia) and El Castillo (Spain).

Researchers believe the impressions may have been made by children aged 7 and 12. The traces were not imprinted during normal locomotion or by the use of hands to stabilize. As a result, researchers argue that deliberate track-making was an early parietal art act.

📣 Our WhatsApp channel is now LIVE! Stay up-to-date with the latest news and updates, just click here to follow us on WhatsApp and never miss a thing!!

As these results researchers point out, what constitutes art is a controversial issue. Even if the traces are not considered art, it is the oldest evidence of the existence of hominins on the Tibetan Plateau, which is called the “Roof of the World”.

The team that made the discovery debated whether the find could be a work of art in a joint article they published on ScienceDirect.

The scientists who evaluated the human hand and footprints and the article revealed by Zhang and his team shared the following.

It is still up for debate whether the impressions on the rock can qualify as the world’s oldest parietal art.

Paul Taçon, a professor of anthropology and archaeology at Griffith University in Australia, believes it might be “a stretch” to call the impressions art.

“The ‘impressions’ reported from Tibet could have resulted from a range of activity and we simply cannot state emphatically that they were made as a purposeful artistic creation,” Taçon told Time.

University of Oxford Professor Nick Barton questioned, “I agree from their patterning that the footprints don’t look like straight-forward tracks but could they be the kinds of traces left behind by kids at play?”

But for Zhang, the debate all boils down to context and the conception of what art is. “When you use stone tools to dig something in the present day, we cannot say that that is technology. But if ancient people use that, that’s technology,” stated Zhang.