In a discovery that deepens our understanding of ancient Mesopotamian spiritual and civic life, archaeologists working under Türkiye’s “Heritage for the Future” (Geleceğe Miras) project have uncovered a substantial public building dating to the Iron Age in the sacred site of Sogmatar. The find, located about four years into ongoing excavations near Yağmurlu village in the Eyyübiye district, pushes the occupational and ritual chronology of the site further back than previously confirmed.

The Discovery: Seven Room Complex from the Neo-Assyrian Era

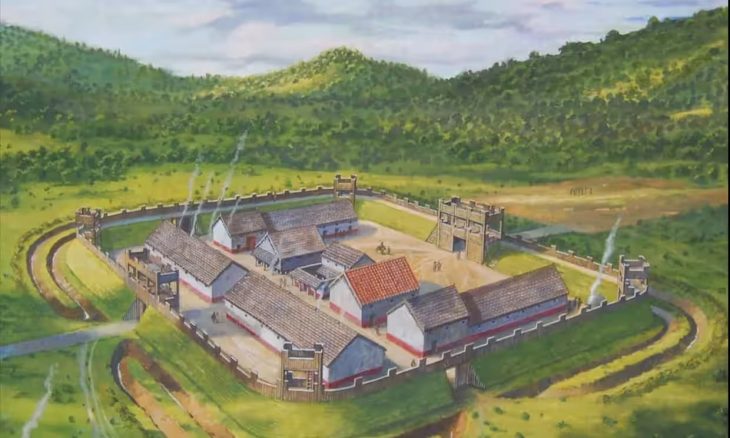

Sogmatar’s excavation team, led by Dr. Süheyla İrem Mutlu in coordination with the Şanlıurfa Museum under Celal Uludağ, identified a structure comprising seven adjoining rooms. Each room features walls standing up to two meters in height, with thickness of about one meter. Preliminary typological and stratigraphic evidence suggests the structure belongs to the Iron Age, possibly aligned with the Neo-Assyrian period (first millennium BCE).

Though Soğmatar has long been known for its rock-cut tombs and religious iconography (notably lunar and solar reliefs), this is the first time that a large-scale public or administrative complex has been exposed at the site. Dr. Mutlu emphasized that this building likely signals that Sogmatar was not simply a cult center or necropolis, but also performed civic or ceremonial functions. Its presence hints at a more integrated urban and ritual planning than previously understood.

From Necropolis to Civic Hub: Revising the Role of Soğmatar

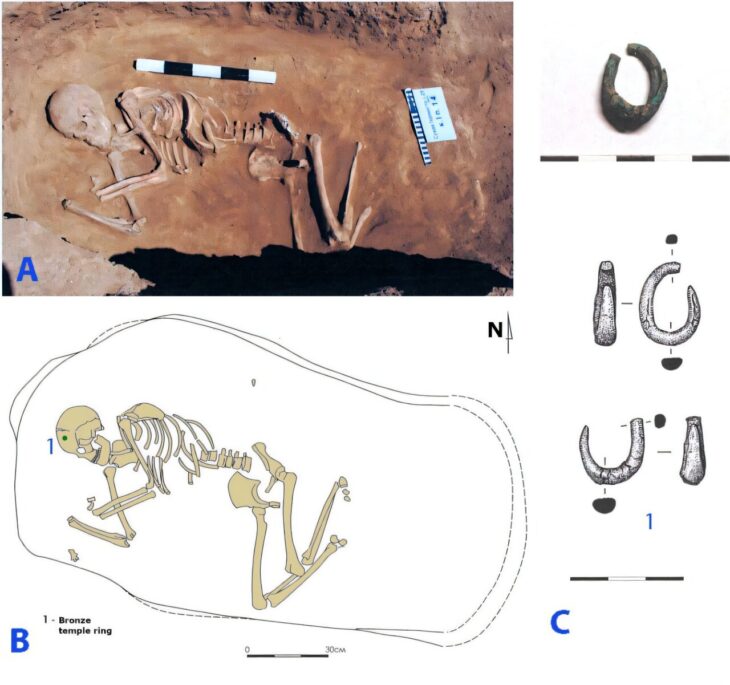

Excavations have also revealed the site’s extensive necropolis. To date, archaeologists have revealed 83 rock-cut tombs, spanning periods from the Early Bronze Age to Roman times. Among these, early shaft-type tombs (circa 2400 BCE) and later entrance-and-stair tombs (Roman era) stand out as two distinct typologies. This range confirms continuous use of the site as a sacred burial ground across millennia.

Until now, most scholarship has framed Sogmatar as primarily a religious or funerary site—a “mountain of the gods,” so to speak. But the newly discovered building allows a more nuanced reading: Sogmatar likely blended sacred, civic, and mortuary functions. The dual excavation of the mound (höyük) and its surrounding necropolis is revealing the spatial logic that tied ritual, administration, and burial together.

📣 Our WhatsApp channel is now LIVE! Stay up-to-date with the latest news and updates, just click here to follow us on WhatsApp and never miss a thing!!

A Cosmos Carved in Stone: Sogmatar’s Astral Landscape

Sogmatar has long been associated with celestial cults. Its carved reliefs, inscriptions, and anatomical alignment with planetary symbolism suggest the site functioned as a cosmic sanctuary. Some scholars believe Soğmatar may have operated as an open-air counterpart to Harran—the great center of lunar worship—in effect an astral axis in the region.

One intriguing hypothesis posits that Sogmatar may have served as an ancient observatory: historian Theodor Hary argued it was designed (in the 1st or 2nd century CE) to mirror the positions of planets and constellations in Harran’s night sky.

The newly uncovered public structure may thus tie into that cosmic vision, possibly serving as a ceremonial pavilion or administrative center for rituals aligned with lunar or planetary cycles.

Sogmatar in Time and Space: Legends, Position, and Continuity

Sogmatar lies about 53 km from Harran, and roughly 15 km from the old settlement of Şuayib (often associated with regional sacred lore).

According to local tradition and some traditional sources, the site is even linked to Prophet Moses’s journey—legends claim that Moses passed through or temporarily settled in the region, meeting his father-in-law Shuayb.

Historical accounts suggest Sogmatar’s character transformed over time. It is said that in 165 CE, when Parthian incursions threatened Urfa, migrants fleeing southward established or reinforced the settlement, preserving its cultic identity well into the Islamic period.

Harran: The Lunar Capital and Cultural Anchor

To appreciate Sogmatar fully, we must place it in the orbit of Harran, one of Mesopotamia’s most enduring sacred cities. Harran is documented as early as the 3rd millennium BCE and functioned as a commercial, religious, and cultural hub.

Central to Harran’s identity was its temple complex dedicated to the moon-god Sin (also known in earlier Sumerian contexts as Nanna). Under the Assyrians and later regimes, Harran’s lunar cult became institutionalized; its Eḫulḫul (Temple of Rejoicing) was refurbished by kings like Shalmaneser III and Ashurbanipal.

Harran’s reputation as a pagan bastion persisted into the Islamic centuries—remarkably, pagan rituals and beliefs were tolerated there long after Christianization had overtaken neighboring cities. Harran remained a center of learning, astronomy, and theology well into the

While Sogmatar is not as grandiose as Harran, its role in the “lunar network” of the region has long been assumed. This new public building underscores how Sogmatar might have functioned as a subordinate node in Harran’s celestial and administrative geometry.

Implications and Next Steps

This discovery has at least three major implications:

Chronological deepening: Sogmatar’s history now demonstrably extends into the Iron Age, giving greater weight to arguments that the site’s ritual and communal functions are far older than surface architecture suggested.

Functional rethinking: The presence of a sizable public building forces scholars to move beyond labeling Soğmatar purely as a cultic or necropolis site. It likely bore administrative, ceremonial or perhaps even judicial roles.

Regional integration: The finding ties Sogmatar more firmly into the sacred geography of Harran and Mesopotamia’s astral cult tradition, underscoring how political, religious, and cosmic dimensions intertwined in the ancient Near East.

Subsequent work will include detailed architectural analysis, epigraphic recovery, and comparative studies with near sites in Harran and Göbekli / Karahan Tepe environs. The excavation team hopes eventually to publish site plans and perhaps reconstruct models of how Sogmatar’s sacred structures related to sky alignments.

For now, the newly uncovered building enriches the narrative: Sogmatar was not merely a mountain of graves and reliefs, but a living node in a cosmic civilization—an intersection of worship, governance, and astronomical imagination.

For a deeper look into the history, mythology, and archaeology of Sogmatar, check out our in-depth feature: “Sacred Hill of Moon God Sin “Sogmatar.”