Beneath the waves between Java and Madura, scientists have unearthed the first underwater fossils of Homo erectus— revealing a lost world once teeming with life.

A Lost World Rises from the Sea

For the first time, scientists have uncovered fossilized remains of ancient humans from a landscape that no longer exists — a land now swallowed by the sea between Java and Madura. Two skull fragments dredged from the Madura Strait, north of Surabaya, have been identified as belonging to Homo erectus, the long-lived ancestor of modern humans that once roamed Southeast Asia.

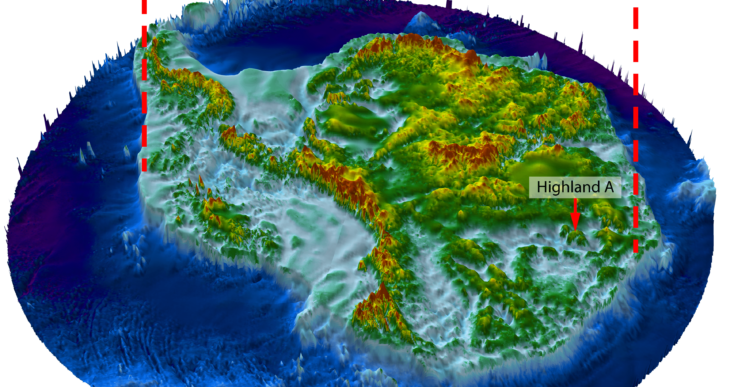

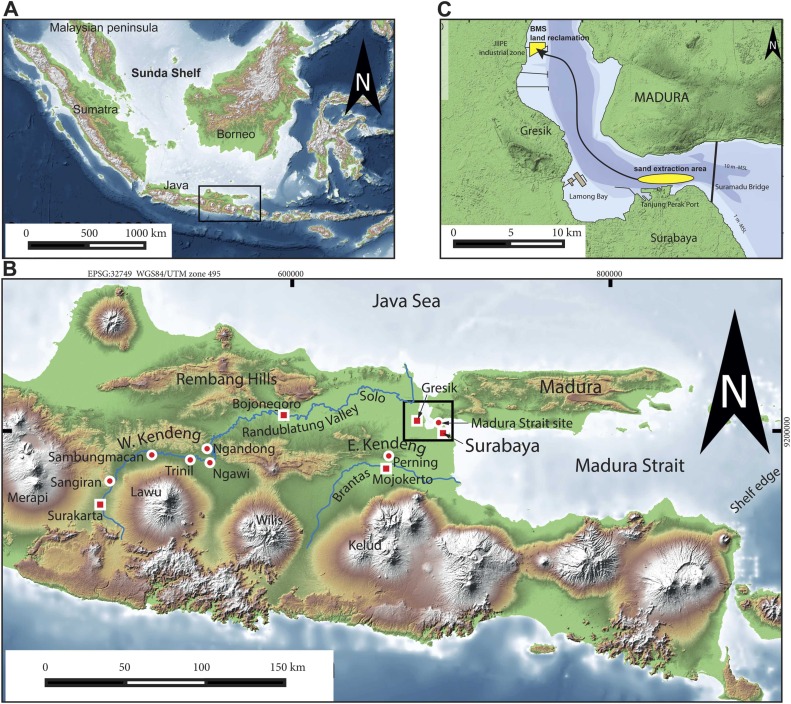

The discovery, reported by an international team from Leiden University, the University of Tokyo, and Indonesia’s Geological Museum Bandung, marks the first hominin fossils ever recovered from the submerged Sunda Shelf, a vast plain that once connected many of today’s Indonesian islands. Their find offers a rare glimpse into life in Sundaland, a prehistoric continent that thrived before rising seas drowned it some 130,000 years ago.

Lead author Harold W. K. Berghuis describes the moment succinctly: “We realized we were holding the bones of humans who had lived on land that is now deep underwater. It changes how we see the story of Java Man.”

Unearthing Bones from Beneath the Sea

The fossils emerged by chance during sand-dredging operations between 2014 and 2015, when around five million cubic meters of seabed material were removed to build an artificial port island near Gresik, Java. After the work finished, locals and researchers noticed the reclaimed ground glittered with fossils — more than 6,700 vertebrate remains, from ancient elephants and buffaloes to the two crucial hominin skull pieces that would rewrite regional prehistory.

📣 Our WhatsApp channel is now LIVE! Stay up-to-date with the latest news and updates, just click here to follow us on WhatsApp and never miss a thing!!

Dating analyses using optically stimulated luminescence (OSL) revealed that the ancient river valley where the bones originated was active between 162 000 and 119 000 years ago, during the Marine Isotope Stage 6 glacial period. At that time, sea levels were far lower, exposing the Sunda Shelf as a fertile lowland traversed by massive rivers such as the Solo River, which once extended far beyond modern Java into what is now the Madura Strait.

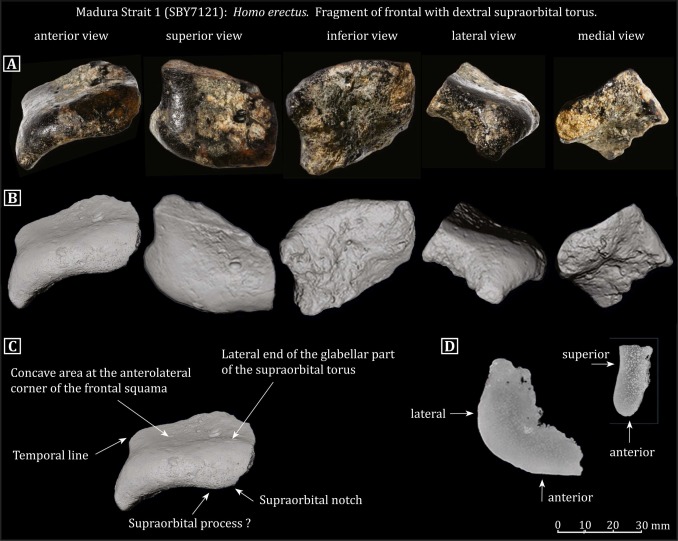

The fossilized bones — a right frontal fragment and a parietal piece of skull — were preserved in these ancient river sands, later buried and sealed beneath marine sediments as the ocean reclaimed the valley.

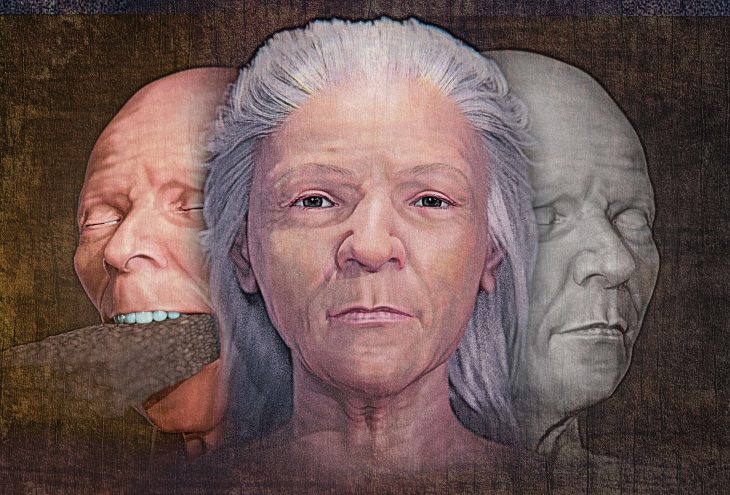

Who Were the Madura Strait People?

Detailed CT scans and morphological comparisons show the fossils closely match those of late Homo erectus individuals from Ngandong and Sambungmacan in central Java. These well-known sites, situated along the upper Solo River, had long represented the youngest known population of Homo erectus on Earth. The new finds confirm that these hominins were not confined to inland Java but ranged widely across the now-vanished plains of Sundaland.

The frontal bone from the Madura Strait displays a straight brow ridge and weak post-orbital constriction, hallmarks of the later Javanese Homo erectus rather than earlier, more primitive forms. It also lacks the pronounced frontal sinus cavities typical of earlier skulls, suggesting an evolutionary refinement toward lighter cranial architecture.

Interestingly, the researchers note the brow ridge of this specimen is thinner than most adult examples — perhaps belonging to a young or more gracile individual. Even so, the anatomy firmly places it within the Ngandong/Sambungmacan/Ngawi paleodeme, a term used to describe the final evolutionary phase of Homo erectus in Java.

Life on the Lost Continent of Sundaland

During the Middle Pleistocene, Sundaland was a sprawling tropical landmass connecting Sumatra, Java, Borneo, and the Asian mainland. Instead of islands, the region formed a continuous expanse of savannas, forests, and river valleys that provided abundant food and water. Fossil fauna from the Madura Strait — including ancient elephants (Stegodon trigonocephalus), wild buffaloes, and deer — paints a picture of open, grassy landscapes dotted with large herds and perennial rivers.

Such environments would have been ideal for Homo erectus, who relied on river corridors for fresh water, tool-making stones, and animal prey. The study’s authors propose that these waterways acted as lifelines across the exposed Sunda Shelf, allowing hominins to migrate, hunt, and perhaps interact with other populations, long before the sea reclaimed their world.

When the ice melted and seas rose around 130 000 years ago, these plains vanished beneath the waves. The people who once lived there either perished or retreated to the higher lands of Java — leaving behind a ghost landscape now buried beneath 30 meters of mud and clay.

Why This Discovery Matters

Until now, every Homo erectus fossil from Southeast Asia had come from dry land sites. The Madura Strait discovery proves that underwater fossil deposits can survive and even hold key evidence of human evolution.

“This changes the game,” says co-author Yousuke Kaifu of the University of Tokyo. “We now know that important parts of our evolutionary history lie on the sea floor. Sundaland may contain many more clues about how early humans adapted to changing climates and landscapes.”

The find also fuels the debate over how Homo erectus interacted with other archaic humans in the region — such as the tiny Homo floresiensis of Flores Island and the mysterious Denisovans, whose genetic traces still linger in the DNA of modern Australians and Papuans. Could the lowlands of Sundaland have served as a crossroads for these ancient populations? For now, the fossil record is too sparse to tell — but the Madura Strait hints that answers may lie hidden beneath the waves.

A New Frontier: Subsea Archaeology

The researchers call their work the beginning of “subsea zooarchaeology” — exploring ancient human habitats now lost to the ocean. Modern technologies like high-resolution sonar mapping and underwater excavation could soon reveal entire Pleistocene landscapes on the Sunda Shelf.

The implications reach far beyond Indonesia. As global sea levels rise today, the submerged history of Sundaland reminds us that coastlines have always shifted, taking whole civilizations — or species — with them.

“Every grain of sand we lift from the seabed could hold a chapter of human history,” Berghuis reflects. “We are just beginning to read the story.”

Berghuis, H. W. K., Kaifu, Y., Wibowo, U. P., van Kolfschoten, T., Sutisna, I., Noerwidi, S., Adhityatama, S., van den Bergh, G., Pop, E., Suriyanto, R. A., Veldkamp, A., Joordens, J. C. A., & Kurniawan, I. (2025). The late Middle Pleistocene Homo erectus of the Madura Strait, first hominin fossils from submerged Sundaland. Quaternary Environments and Humans, 3, 100068. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.qeh.2025.100068

Cover Image Credit: Public Domain