Across continents and thousands of years, two ancient mythological figures—one rooted in the Korean Peninsula, the other spanning the vast Turkic world—may share surprising conceptual and symbolic parallels. A recent comparative cultural study is drawing fresh scholarly attention to Mago Halmi, a primordial Korean creator goddess, and Umay Ana, the maternal protector spirit of Turkic mythology (known in various Turkic linguistic traditions as Umay Ene, Nana Umay, Humay, and in Bashkir folklore as Homay), revealing how distant societies may have developed strikingly similar sacred feminine archetypes.

The research, conducted by researcher Hyunjoo Park, examines how these two mythological figures functioned as creators, guardians of childbirth, and symbols of life itself. The findings suggest that mythological narratives often preserve ancient cultural memory, encoded long before written history emerged.

Myth as Cultural Memory and Social Blueprint

For centuries, myths have served as more than folklore or entertainment. They reflect humanity’s attempt to explain the natural world, social structure, and spiritual beliefs. The study highlights that both Korean and Turkic mythological traditions rely heavily on oral transmission, meaning stories evolved regionally while preserving core symbolic meanings.

In Korean mythology, Mago Halmi is described as a colossal divine grandmother who shaped the physical world—creating mountains, rivers, and landscapes through supernatural acts. The figure appears in ancient narrative traditions and is associated with the earliest cosmological myths of Korea.

Meanwhile, in Turkic mythology, Umay Ana emerges as a sacred maternal figure who protects pregnant women, newborns, and children. She is frequently described as a life-giving and protective spiritual entity deeply integrated into early Turkic cosmology and social life.

📣 Our WhatsApp channel is now LIVE! Stay up-to-date with the latest news and updates, just click here to follow us on WhatsApp and never miss a thing!!

Although separated geographically, both figures represent the ancient human tendency to conceptualize cosmic creation and human reproduction through maternal symbolism.

Shared Roles: Creator, Birth Goddess, and Protector

One of the most striking similarities identified in the study is the shared functional role of the two goddesses. Both Mago and Umay appear in mythological narratives as creators linked to the origins of humanity and the natural environment.

According to Korean mythological traditions, Mago was believed to have shaped the physical landscape and even produced human ancestors without conventional reproduction. Over time, however, her divine status evolved, and in some traditions, she transformed into a birth-related goddess associated with fertility and infant care.

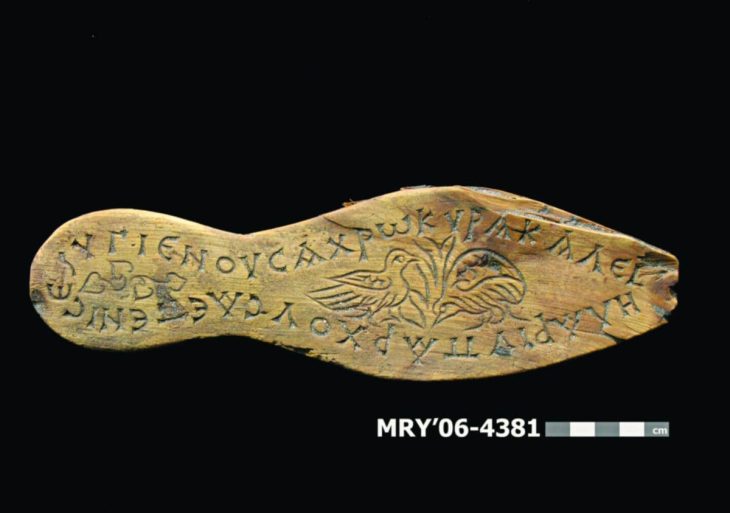

Similarly, Umay Ana holds a central place in Turkic belief systems as a guardian spirit responsible for fertility, childbirth, and child protection. Historical references to Umay appear in early Turkic inscriptions and oral traditions, where she is portrayed as a divine force influencing both physical and spiritual well-being.

The research suggests that these overlapping roles may reflect universal human concerns regarding survival, fertility, and maternal protection—key themes in many ancient mythologies worldwide.

Linguistic Clues Suggest Deeper Symbolic Connections

Beyond narrative parallels, the study explores potential linguistic similarities between the names and symbolic meanings of the two goddesses.

The term “Mago” is interpreted as containing linguistic elements related to motherhood and sacred femininity, with “ma” often symbolizing maternal identity in multiple Eurasian language traditions. In Korean cultural interpretations, Mago is associated with cosmic creation and life-giving energy.

The name “Umay,” on the other hand, may derive from ancient Turkic linguistic roots connected to motherhood, fertility, and protective spiritual forces. In some early Turkic contexts, the word is also associated with the placenta, symbolizing life and birth itself.

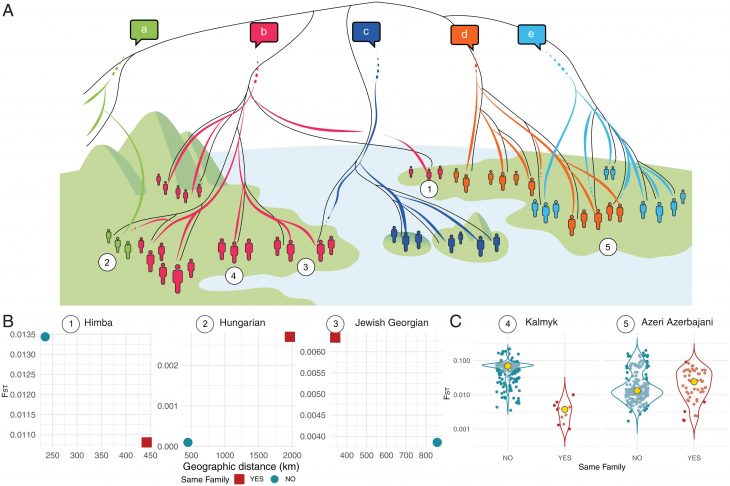

The study notes that similar symbolic associations appear in Korean traditions, where terms connected to childbirth and maternal care share conceptual parallels with Umay’s functions. These linguistic intersections are not presented as proof of direct cultural transmission, but they highlight how mythological language often reflects shared human perceptions of birth and creation.

From Sacred Mothers to Ambivalent Spirits

Another fascinating element of the research focuses on how both figures underwent dramatic transformations over time. As societies shifted from matriarchal or female-centered spiritual systems toward patriarchal religious structures, the roles of these goddesses evolved.

In certain Korean folk traditions, Mago eventually transformed into darker or ambivalent spiritual figures, sometimes portrayed as harmful or destructive entities. Scholars suggest this transformation may reflect changing gender hierarchies and social ideologies during Korea’s Confucian period.

Comparable transformations appear in Turkic folklore. In some traditions, Umay evolves into figures associated with Albastı, a spirit believed to threaten mothers and infants during childbirth. This shift, researchers argue, may reflect the cultural transition from early matrilineal belief systems toward patriarchal social structures.

The parallel evolution of these mythological figures suggests that religious transformation often mirrors societal change rather than purely theological reinterpretation.

Birth, Protection, and Ancient Ritual Practice

Both mythological systems reveal deep ritual connections to childbirth. Korean traditions describe ceremonial offerings to birth goddesses, including ritual meals prepared to ensure a newborn’s survival and health.

Similarly, Turkic communities historically developed protective customs during pregnancy and postpartum periods, often invoking Umay’s protection through symbolic rituals and folk practices. These traditions persisted across Central Asia and Anatolia, demonstrating the enduring cultural significance of maternal protective spirits.

Researchers argue that such practices highlight how mythological belief systems often functioned as early forms of social and psychological healthcare in pre-modern societies.

A Cross-Cultural Reflection of Ancient Feminine Divinity

The comparative analysis ultimately suggests that Mago Halmi and Umay Ana represent two manifestations of a broader Eurasian tradition of sacred maternal deities. Both figures embody creation, fertility, and spiritual guardianship, reflecting universal human concerns that transcend geography.

The research also demonstrates how mythology can reveal hidden cultural connections, even when historical migration or direct cultural exchange remains uncertain. By examining linguistic, symbolic, and ritual parallels, scholars are uncovering new ways to understand how ancient societies conceptualized life, gender, and cosmic order.

As archaeological, linguistic, and anthropological research continues to expand, studies like this may reshape modern understanding of early Eurasian belief systems—revealing that mythological storytelling may preserve traces of shared human memory stretching far beyond national or regional boundaries.

Park, H. (2024). Kore’deki “Mago Halmi” ile Türk dünyasındaki “Umay Ana”nın karşılaştırılması. ÇAKÜTAD, 4(2), 158–170. https://doi.org/10.71096/cakutad.1538710

Cover Image Credit: Artistic reconstruction generated by the author using AI technology, inspired by mythological and folkloric descriptions.