Archaeologists in Spain have uncovered nearly 1,000 inscriptions at the Iberian site of Azaila, revealing the largest archive of pre-Roman writing in Hispania and offering rare insight into everyday literacy, trade, and daily life before Roman conquest.

On a low hill overlooking the Ebro Valley in northeastern Spain, archaeologists have uncovered something far more revealing than monumental temples or heroic statues. At the site known as Cabezo de Alcalá, near today’s town of Azaila in Teruel, nearly one thousand inscriptions scratched onto everyday objects have transformed how scholars understand literacy in pre-Roman Iberia.

The city’s original name remains unknown. Its fate, however, is clear. Sometime between 76 and 72 BC, during the violent Sertorian Wars that shook Roman Hispania, the settlement was destroyed and abandoned. What survived was not its architecture, but its words—preserved on plates, jars, amphorae, and weights used by ordinary people in their daily lives.

According to a comprehensive new study published in Palaeohispanica, this assemblage represents the largest known archive of Palaeohispanic inscriptions ever found at a single site. And unlike official decrees or funerary monuments, these texts capture something rarer: the routine language of work, trade, storage, and household organization.

Writing Beyond Elites: A City That Lived With Text

The inhabitants of Azaila belonged to the Sedetani, an Iberian people who lived at the crossroads of Iberian, Celtiberian, and Roman worlds. Far from being marginal, writing was woven into the fabric of daily life. Nearly all inscriptions—more than 96 percent—are written in the Iberian language, while a small but significant number appear in Latin, reflecting growing Roman influence before the city’s destruction.

📣 Our WhatsApp channel is now LIVE! Stay up-to-date with the latest news and updates, just click here to follow us on WhatsApp and never miss a thing!!

What makes Azaila exceptional is not only the quantity of texts but their function. Writing was not reserved for priests, elites, or official spaces. It appeared in kitchens, storerooms, and marketplaces. Plates were marked to identify their user. Amphorae were labeled with names, weights, or contents. Even humble clay weights bore symbols and letters that conveyed practical information.

This pattern challenges older assumptions that Iberian literacy was limited or ceremonial. Instead, the evidence suggests a society where basic writing skills were widely shared, at least to the degree needed for marking and recognizing signs.

Two Pottery Worlds, Two Writing Habits

The inscriptions reveal a striking contrast between imported Roman goods and locally produced Iberian ceramics.

On Italian black-gloss pottery, considered luxury tableware, inscriptions tend to be short—often just one or two letters—and placed in discreet locations such as the base or underside of a vessel. Scholars believe these marks helped identify objects during storage while preserving the aesthetic value of prized items.

Local Iberian pottery, by contrast, tells a different story. Here, inscriptions are longer, more visible, and boldly positioned on the exterior walls or rims of vessels. These texts were meant to be read during use, not hidden away. The difference reflects two parallel attitudes toward writing: one discreet and conservative, the other open and functional.

Names, Words, and the Language of Ownership

Many inscriptions consist of personal names, sometimes abbreviated, sometimes complete. One especially clear example reads etesike-en-ni, interpreted as “belonging to Etesike,” using possessive particles characteristic of the Iberian language. Other names appear repeatedly in shortened forms, suggesting a shared understanding of identity markers within the community.

Yet not all words are names. On locally made pottery, researchers have identified longer sequences that likely belong to everyday vocabulary, a rare glimpse into the spoken Iberian language. One recurring root, kutu-, appears on multiple objects and is associated with writing itself—possibly meaning “text” or “inscription.”

Even more intriguing is the appearance of the word belenos on two amphorae. Linguists suggest it may be a borrowing from Celtiberian, referring to henbane, a toxic plant used medicinally and ritually. If correct, the inscriptions may record not only trade but also specialized contents mixed with wine or other liquids.

Commerce Written on Clay

The strongest evidence for practical literacy appears on amphorae and storage jars, where writing intersected directly with trade. These vessels carry names, numerical marks, stamps, and painted labels—some in Iberian, others in Latin—recording information about ownership, capacity, age of wine, or fiscal control.

One painted Latin inscription identifies wine as vetus—four years old—a valuable commodity at the time. Such details reveal an economy in which Iberian and Roman systems overlapped, cooperating rather than competing. Roman-produced amphorae circulated through Iberian hands, marked and remarked as they moved through networks of exchange.

Signs for Those Who Did Not Write

Not everyone needed full literacy to participate. Around 10 percent of the markings are non-alphabetic symbols: crosses, X-shapes, vertical lines, and even a five-pointed star found on a coordinated set of tableware. These symbols formed a shared visual language, allowing users to distinguish objects without writing words.

Such marks blur the line between literate and non-literate behavior. They show how meaning could be conveyed through signs alone, reinforcing the idea that communication in Azaila was inclusive, adaptive, and deeply practical.

A City Frozen Before Silence

Azaila’s destruction, sudden and violent, sealed this archive in place. Unlike cities that evolved gradually under Roman rule, Cabezo de Alcalá offers a snapshot of Iberian society just before disappearance. There are no grand inscriptions praising rulers or gods. Instead, there are plates, jars, and weights—each carrying traces of human intent.

Together, these nearly one thousand inscriptions form an unparalleled record of how writing functioned in an ancient city, not as an abstract skill, but as a daily habit. Azaila may have lost its name, but through these marks, its people still speak—quietly, practically, and unmistakably human.

López Fernández, A. (2025). Azaila: Writing in an Iberian city. Palaeohispanica, 25, 227–254. https://doi.org/10.36707/palaeohispanica.v25i1.710

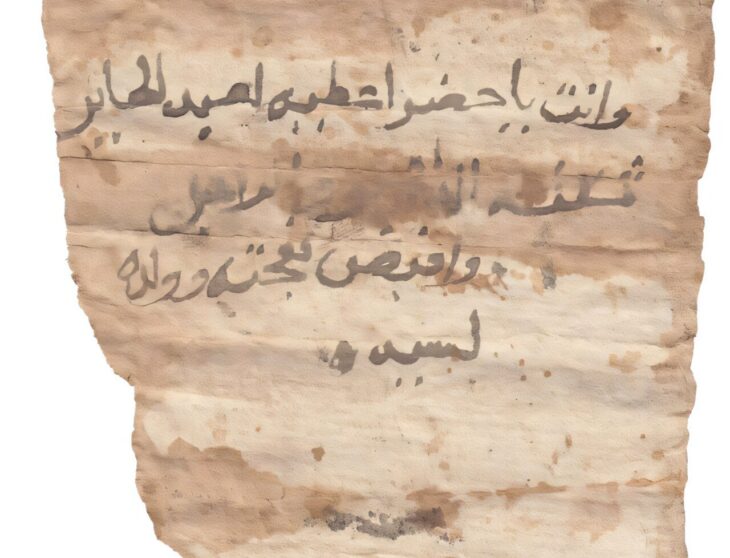

Cover Image Credit: Public Domain – Wikipedia Commons