Recent research on the Parthenon Sculptures has found traces of the original paint used to decorate the Parthenon Sculptures, revealing that these statues were once fact brightly colored.

Also known as the Elgin Marbles, the Parthenon Sculptures are a collection of marble decorative statues taken from the temple to Athena on the Acropolis in Athens.

Exhibited at the British Museum, the Parthenon Sculptures, originally from ancient Greece, have for centuries been admired for their white brilliance – yet new evidence finally proves they haven’t always been this colour.

The sculptures are from Athens’ Parthenon, an ancient temple within the Acropolis, a citadel perched atop a rocky outcrop overlooking the city. The gleaming marble temple, which has become synonymous with ancient Greece, was dedicated to the goddess Athena in the mid-5th century B.C. Its elaborate decorative sculptures depict scenes from ancient Greek mythology.

A team of investigators from King’s, the British Museum, and the Art Institute of Chicago used digital imaging techniques and scientific instrumentation to examine the sculptures at microscopic level, and discovered a “wealth of surviving paint”, revealing that the sculptures had originally been painted in multiple colours, patterns and designs.

📣 Our WhatsApp channel is now LIVE! Stay up-to-date with the latest news and updates, just click here to follow us on WhatsApp and never miss a thing!!

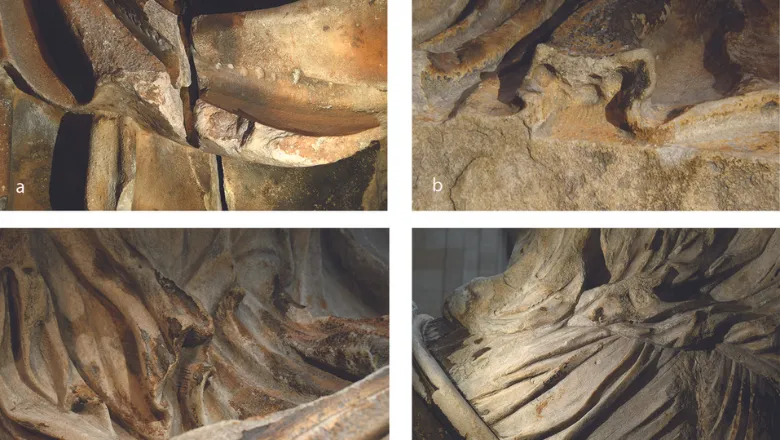

“Even if the surfaces were not explicitly prepared for the application of paint, however, carving and color were unified in their conception. The Parthenon artists were sympathetic to the final intended polychrome sculpture, providing surfaces that evoked textures similar to those of the subjects represented. It is likely that the painters took advantage of these mimetic surfaces to achieve the final effects,” says Dr. Will Wootton, Reader in Classical Art and Archaeology and Head of Classics Department.

Researchers used visible-induced luminescence imaging on the Parthenon Marbles in the British Museum, a non-invasive technique developed by Dr Giovanni Verri from the Art Institute of Chicago that can detect microscopic traces of a pigment called Egyptian blue, revealing the tiniest remnants of paint and patterns.

Egyptian blue is a man-made pigment composed of calcium, copper and silicon; it was already used in Egypt around 3000 BCE and was virtually the only blue pigments used in Greece and Rome.

Small traces of white and purple pigment were also detected on the sculptures. True purple pigment was very valuable in the ancient Mediterranean and was produced from shellfish, but the Parthenon purple apparently was not.

Paint does not often survive over time, especially when exposed to the elements throughout the centuries, and so by the time ancient Greek sculptures were being studied, most of the colour had already worn away. This meant for a long time many believed that ancient Greek art only used white marble.

Additionally, historic restorations have often removed any lasting traces of paint, to reestablish the assumed original ‘whiteness’ of the sculpture. This has made it difficult to understand and reconstruct the sculptures’ original appearance.

“The Parthenon Sculptures at the British Museum are considered one of the pinnacles of ancient art and have been studied for centuries now by a variety of scholars. Despite this, no traces of color have ever been found and little is known about how they were carved,” notes Dr Giovanni Verri.

The carving of the sculptures shows no distinct technical intervention between the surface finish of the marble and the application of paint. Instead, it indicates that the sculptors focused on reproducing the intended form (e.g. wool, linen, skin, etc), rather than crafting a special surface for the adhesion of paint through, for example, keying or abrasion.

These preliminary findings suggest that the painting of the Parthenon Sculptures was a more elaborate undertaking then ever imagined. This supports the belief that the colours, together with the carvings of ancient Greek sculpture were important for its creators and intended audiences.

The study was published in the journal Antiquity.