For many, the Kamasutra is merely a name linked to condom brands and erotic chocolates, often dismissed as just a “dirty book.” However, this ancient text, rooted in the rich soil of Indian history, offers profound insights into sexual autonomy, particularly for women. By exploring its archaeological elements, we can uncover a narrative that transcends mere eroticism and speaks to the empowerment of women.

The Kamasutra, composed in the ancient Sanskrit language in the 3rd century by the Indian philosopher Vatsyayana, is not just a manual of sexual positions; it is a cultural artifact that reflects the complexities of human relationships and societal norms of its time. The term “kama” encompasses love, desire, and pleasure, while “sutra” signifies a treatise. This text serves as a window into a world where sexual pleasure was not only acknowledged but celebrated.

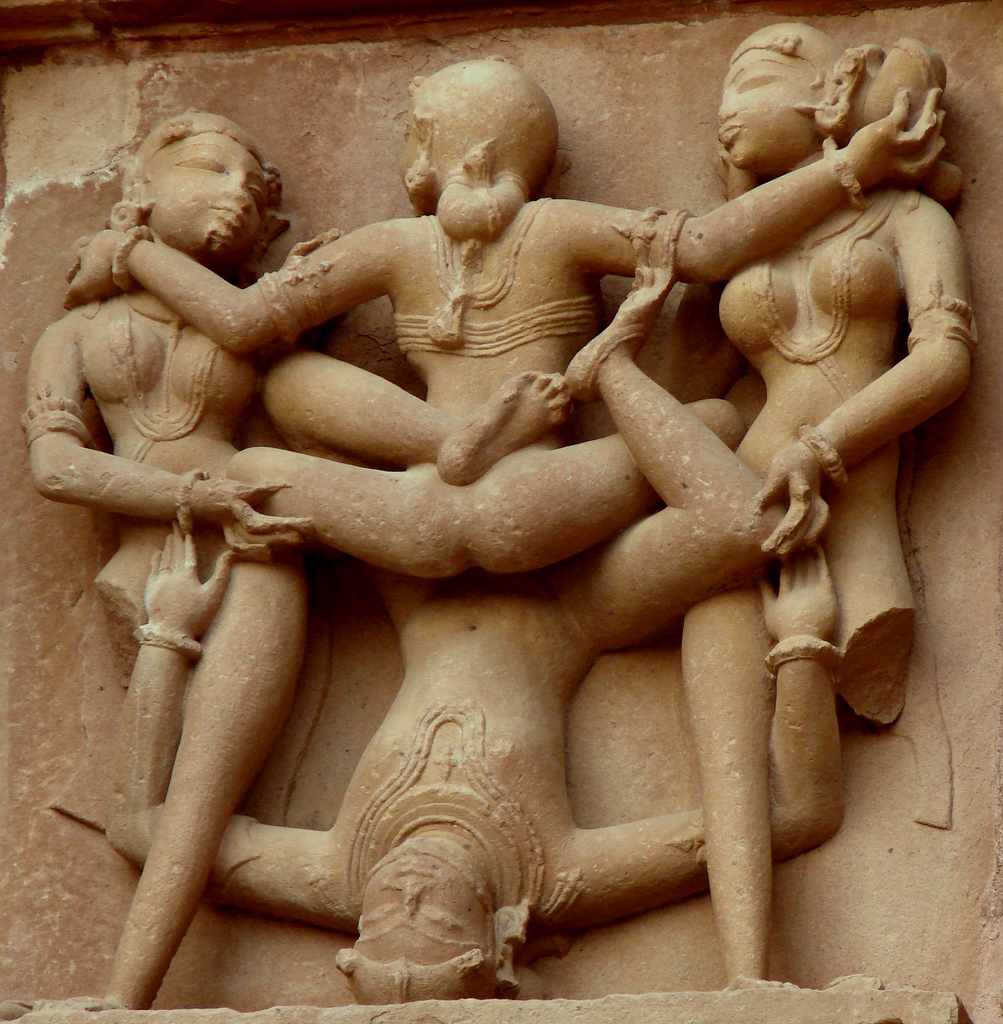

Archaeological findings from ancient India reveal a society that embraced sexuality as a natural part of life. Temples adorned with intricate carvings of couples in various intimate poses illustrate that sexual expression was not shrouded in shame but rather celebrated as an essential aspect of human experience. Notable examples include the Khajuraho temples in Madhya Pradesh, which are famous for their erotic sculptures and intricate designs. Built between 950 and 1050 AD during the Chandela dynasty, these temples showcase a unique blend of spirituality and sensuality. The erotic sculptures depict various aspects of love, relationships, and the human experience, making Khajuraho a UNESCO World Heritage Site and a significant cultural landmark.

In her book, Redeeming the Kamasutra, scholar of Indian culture and society Wendy Doniger emphasizes that Vatsyayana was an advocate for women’s pleasure, advocating for their right to education and the freedom to express desire. This perspective is echoed in the archaeological record, where depictions of women engaging in sexual acts with agency and enthusiasm suggest a society that valued mutual enjoyment and consent.

Other temples, such as the Sun Temple in Konark and the Brihadeeswarar Temple in Thanjavur, also feature erotic sculptures that reflect the same themes of love and desire. The Sun Temple, built in the 13th century, is renowned for its intricate carvings that depict not only deities but also couples in various stages of intimacy. Similarly, the Brihadeeswarar Temple, a UNESCO World Heritage Site, showcases sculptures that celebrate the beauty of human relationships and the divine connection between lovers.

📣 Our WhatsApp channel is now LIVE! Stay up-to-date with the latest news and updates, just click here to follow us on WhatsApp and never miss a thing!!

However, the Kamasutra’s narrative has been distorted over time, particularly following its first English translation by Sir Richard Burton in 1883. Burton’s omissions and alterations shifted the portrayal of women from active participants to passive recipients of male pleasure. This misrepresentation has had lasting effects, contributing to the ongoing suppression of discussions surrounding female sexuality in contemporary Indian society.

Despite the rich archaeological evidence of women’s active roles in intimacy, societal norms continue to dictate that women suppress their desires. Indian sex educator Leeza Mangaldas points out that cultural expectations often silence women, enforcing a narrative that prioritizes male pleasure. This is further reinforced by patriarchal norms that uphold virginity as a virtue for women while imposing no such expectations on men.

Yet, the Kamasutra itself offers a counter-narrative. In its original form, it describes women as vibrant participants in their pleasure, likening their sensuality to delicate flowers that require care and respect. This imagery, supported by archaeological findings, underscores the importance of nurturing and valuing women’s desires.

Sharha, a PhD candidate at Cardiff Metropolitan University, explores the concept of ‘Kamasutra feminism’ in her article published in The Conversation, which posits that this ancient text is not merely about sex but about reclaiming sexual autonomy. It challenges patriarchal norms by promoting women’s freedom to articulate their desires and take control of their pleasure. The Kamasutra advocates for mutual satisfaction and consent, a revolutionary idea that resonates with the archaeological evidence of women’s agency in ancient Indian society.

Doniger describes the Kamasutra as a feminist text, emphasizing its focus on women choosing their partners and engaging in pleasurable sexual relationships. This perspective is crucial in understanding the economic independence that the text recognizes as vital for women’s sexual autonomy. Archaeological findings suggest that women in ancient India had more freedom and agency than often assumed, allowing them to make choices about their bodies and desires.

Ultimately, the Kamasutra represents a clash between the oppressive forces of passions about intimacy, allowing women to reclaim their voices in relationships.

For over a century, the Kamasutra has been misinterpreted, its radical message buried beneath layers of cultural shame and censorship. However, by examining its archaeological context, we can uncover a text that speaks to the importance of consent, equality, and female agency.

Reclaiming the Kamasutra as a guide for sexual empowerment, informed by its archaeological roots, could help dismantle deeply ingrained taboos and reshape the conversation around women’s pleasure. In a world where female desire is still policed, this ancient manuscript serves as a reminder that women’s pleasure is not a luxury but a fundamental right, deserving of recognition and respect.

The erotic sculptures found in temples like Khajuraho, Konark, and Thanjavur not only celebrate the beauty of human relationships but also challenge the modern narrative that often marginalizes women’s sexual autonomy. By revisiting these ancient texts and their artistic representations, we can foster a more inclusive understanding of sexuality that honors both the historical context and the ongoing struggle for women’s rights.

In conclusion, the Kamasutra and the temples of ancient India collectively offer a rich tapestry of insights into the interplay between sexuality, spirituality, and gender. They remind us that the conversation around sexual autonomy is not new; it has deep historical roots that deserve to be acknowledged and celebrated. By embracing this legacy, we can work towards a future where women’s desires are recognized, respected, and fulfilled.

Cover Image Credit: Erotic detail from the base of Lakshana Tempel in Khajuraho. CC BY 2.0