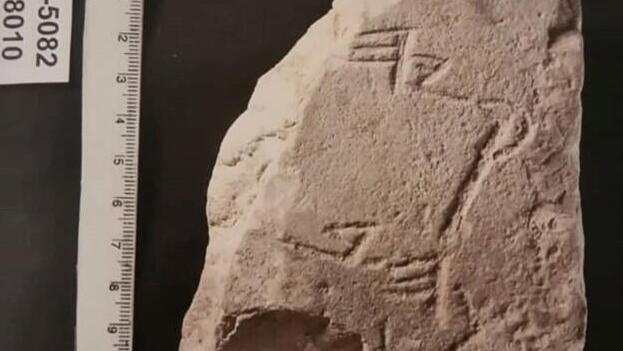

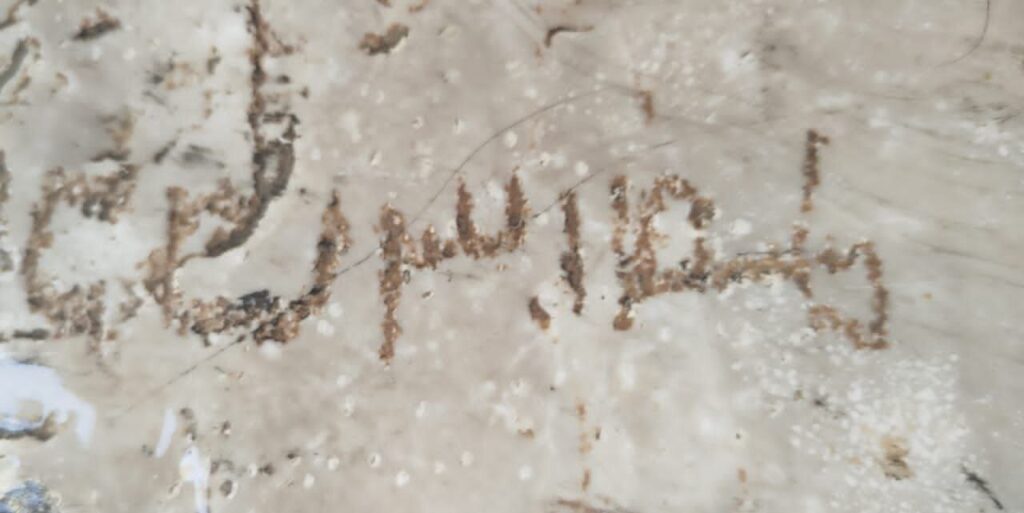

A rare Sassanid-era inscription has been unearthed in the historic region of Marvdasht, located in Iran’s Fars province, revealing deep insights into how ancient Persians viewed loyalty, justice, and the consequences of betrayal.

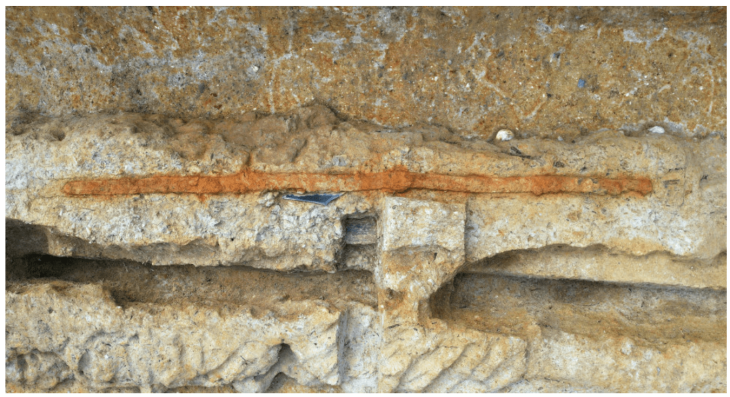

Marvdasht holds a significant place in ancient Persian history. Situated near Persepolis, the ceremonial capital of the Achaemenid Empire, it remained an important cultural and religious center during the Sassanid period (224–651 CE). The region was home to royal inscriptions, fire temples, and key administrative centers. Its mountainous landscape provided ideal locations for monumental carvings and religious sites, making it a symbolic setting for declarations of law and moral conduct.

The discovery, announced by historian Dr. Abolhassan Atabaki, is believed to reflect strong ethical values rooted in Zoroastrian beliefs and the cult of Mithra—the guardian of oaths and truth.

According to Dr. Atabaki, the inscription serves as a moral advisory aligned with the ancient Iranian ethical code. Deeply rooted in the spiritual teachings of Mithra (Mehr)—the Zoroastrian divinity of covenants, truth, and justice—the text condemns oath-breaking as a grave transgression, both socially and cosmically.

“This inscription is a remarkable example of how ancient Iranians viewed loyalty as a sacred value, and betrayal as one of the gravest sins,” Atabaki explained.

📣 Our WhatsApp channel is now LIVE! Stay up-to-date with the latest news and updates, just click here to follow us on WhatsApp and never miss a thing!!

The Sassanid View of Betrayal: A Threat to Order and Nature

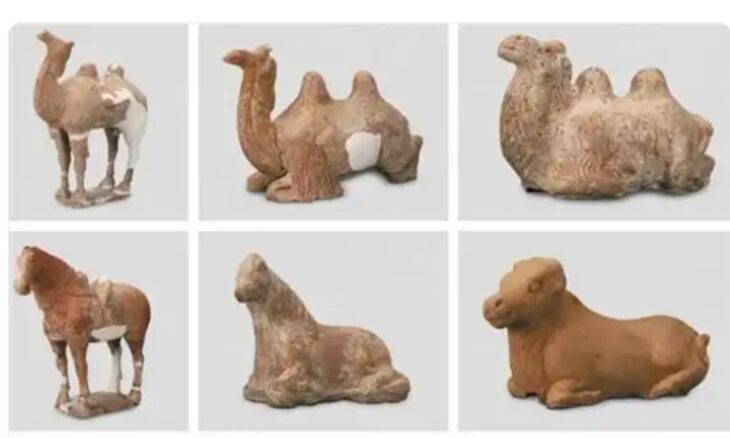

During the Sassanid period (224–651 CE), the last great Persian empire before the advent of Islam, loyalty was more than a moral ideal—it was a divine expectation. Influenced by Zoroastrianism, the dominant religion of the time, the breaking of oaths was believed to invoke the wrath of Mithra, leading to natural disasters such as drought and social instability.

“When a person breaks an oath, Mithra becomes enraged, and the violator’s land suffers—facing drought, disorder, and decline,” Atabaki noted.

This worldview was not limited to religion but extended into governance and justice. Dishonest rulers or corrupt judges were seen as direct contributors to cosmic imbalance. In a society where divine law and civil order were intertwined, public trust was not only a political necessity but a spiritual mandate.

A Glimpse into Zoroastrian Legal Philosophy

The Sassanids, who revived the ancient Persian imperial tradition, placed a strong emphasis on law and order. This was underpinned by Zoroastrian teachings found in the Avesta, which stressed the importance of truth (asha) and condemned the lie (druj). Sacred texts warned that liars and oath-breakers risked being cut off from divine favor and communal trust.

Even mythical covenants, such as the eternal battle and balance between Ahura Mazda and Angra Mainyu, were viewed as binding agreements that could not be violated. To break an oath was to reject the cosmic order itself.

“A person who breaks a vow or lies under oath is likened to one who renounces the Avesta and the teachings of Zoroaster,” said Atabaki.

Mithra: The Divine Enforcer of Social Harmony

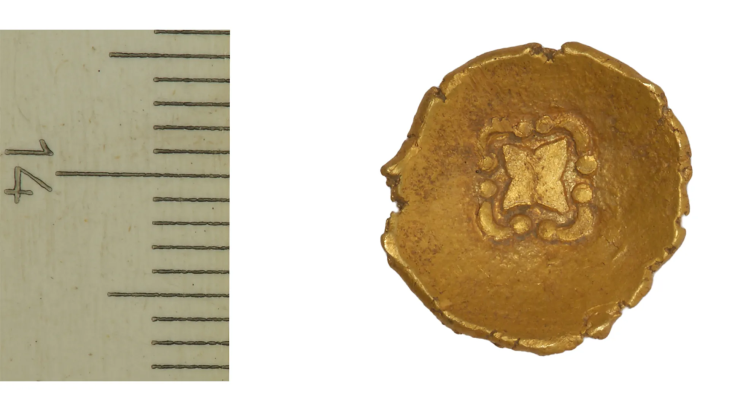

The discovery also underlines the enduring influence of Mithra across the Iranian plateau. Initially venerated in Achaemenid inscriptions and later by Sassanid monarchs such as Ardashir I and Ardashir III, Mithra served as the guardian of warriors, protector of contracts, and overseer of marital and social bonds. In both Iranian and Vedic traditions, the deity symbolized unwavering commitment to truth and harmony.

“In a diverse and vast land like ancient Iran, the foundation of the social order among kings, farmers, nomads, traders, and artisans was built upon the sacredness of pledges,” Atabaki emphasized.

A Testament to Sassanid Ethical Thought

Beyond its spiritual dimensions, the inscription stands as a reflection of the advanced ethical and legal philosophy that characterized the Sassanid Empire. The era is noted for its codification of laws, religious tolerance within the Zoroastrian framework, and a structured judiciary that emphasized the role of divine justice in civil affairs.

As historians and archaeologists continue to analyze the text, the find is expected to deepen our understanding of how ancient Persian society managed the delicate balance between divine command, legal authority, and human relationships.

Cover Image Credit: Taq-e Bostan in Kermanshah city: high-relief of Ardeshir II investiture; from left to right: Mithra, Ardeshir II, Shapur II. Lying down: dead Roman emperor Julian. Public Domain