Archaeologists in Tajikistan have unearthed an exceptionally rare fresco depicting priests performing a fire-worship ritual at the palace of Sanjar-Shah, a major Sogdian site near the historic Silk Road city of Panjikent.

The discovery, announced in the journal Antiquity, sheds light on one of Central Asia’s most vibrant ancient civilizations and offers new insights into the religious life of the Sogdians during Late Antiquity and the Early Islamic period.

A Palace at the Crossroads of the Silk Road

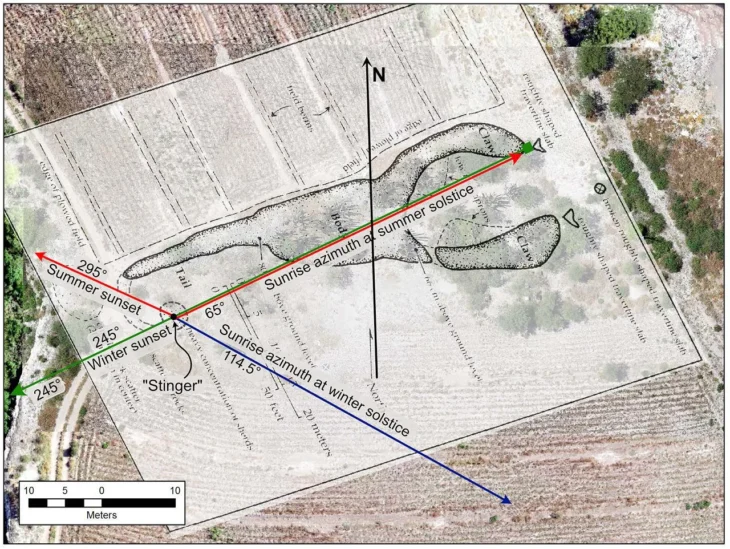

Sanjar-Shah, located in the fertile Zeravshan Valley 12 kilometers east of modern Panjikent, was a political and cultural center in the eighth century CE. Soviet archaeologists first identified the ruins in the late 1940s, but large-scale excavations began only in 2001. By the mid-eighth century, during the rule of Umayyad governor Naṣr ibn Sayyār, Sanjar-Shah had become a fortified town with an elaborate palace, thought to be the residence of the last ruler of Panjikent before the Arab conquest.

Finds from the palace, including a Chinese bronze mirror, a gilded belt buckle, and early Arabic letters written on paper—the earliest such documents known in Central Asia—underscore its elite status and extensive connections across Eurasia. The site was partially destroyed by fire in the third quarter of the eighth century, then reoccupied and subdivided into smaller domestic spaces during the early Samanid era (819–900 CE), offering a rare glimpse into Central Asia’s turbulent transition from pre-Islamic to Islamic culture.

The Fresco Discovery

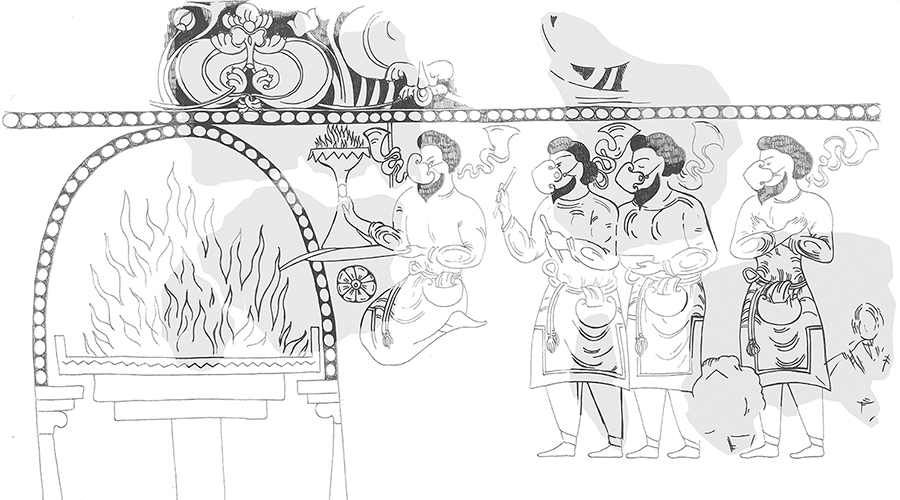

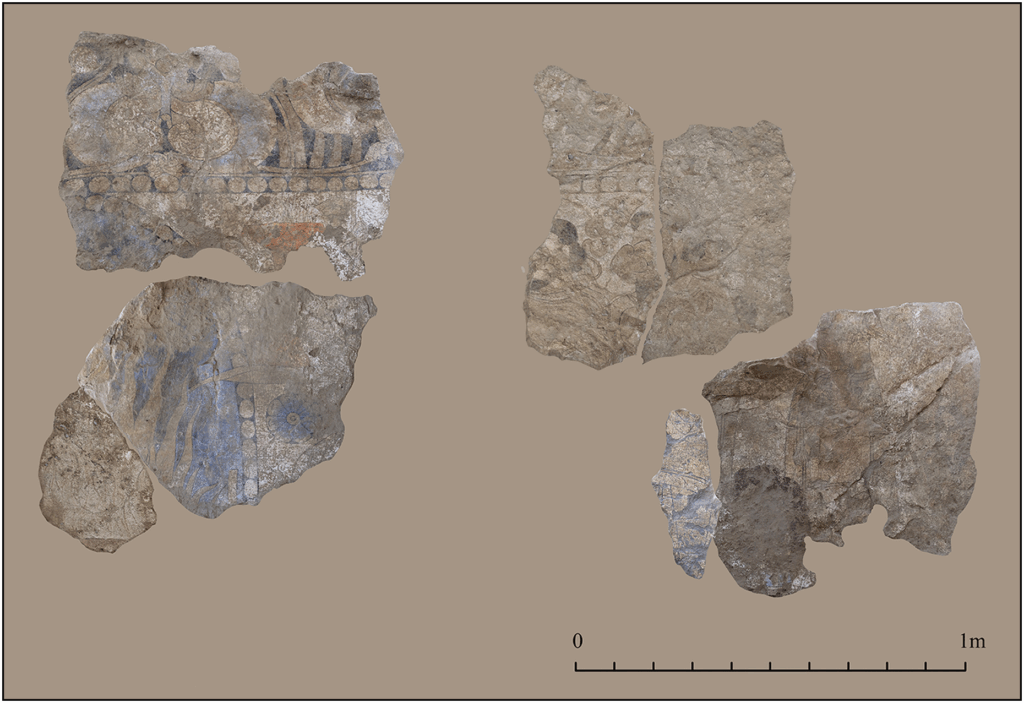

The newly reconstructed fresco was found in the palace’s massive “Rectangular Hall,” a 15.6-by-19-meter reception space unlike any other in Sogdian architecture. Excavations in 2022–2023 uncovered about 30 painted fragments that, when pieced together, revealed a composition measuring roughly 1.5 by 2.5 meters.

📣 Our WhatsApp channel is now LIVE! Stay up-to-date with the latest news and updates, just click here to follow us on WhatsApp and never miss a thing!!

The scene shows four priests, possibly accompanied by a child, walking in solemn procession toward a monumental fire altar beneath an arch—a motif more commonly associated with funerary ossuaries than palace walls. The leading priest kneels on both knees, offering incense on a portable burner, while another figure wears a padām, a ritual mouth covering still used by Zoroastrian priests to prevent impurity from reaching the sacred flame. Other details include belted robes, pouches, and ritual implements, offering a strikingly detailed visual record of Sogdian religious practice.

Fragments from the same hall also depict a battle scene featuring armored warriors and demonic figures, echoing themes from Panjikent’s famed “Blue Hall.” The combination of religious imagery, royal architecture, and martial iconography highlights the complexity of Sogdian courtly culture.

Insights into Sogdian Zoroastrianism

The Sogdians, an Iranian-speaking people who flourished along the Silk Road from the fifth to eighth centuries CE, were instrumental in connecting China, Persia, and the Mediterranean. Their merchants and artisans established trade colonies as far west as Byzantium and as far east as China’s Tang capital, Chang’an. Yet despite their wide influence, little direct evidence survives of their religious rituals.

Lead archaeologist Dr. Michael Shenkar of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem emphasized the fresco’s rarity:

“This is one of the very few depictions of Sogdian priests tending a stationary fire altar outside funerary contexts. It offers an unprecedented view of Zoroastrian ceremonial traditions in Sogdiana during a period of profound political and cultural change.”

The fresco confirms that Sogdian clergy wore simple robes and beards rather than aristocratic attire, and used ritual accessories such as ladles, barsoms (sacred twigs or rods), and portable censers. This imagery bridges a gap between Zoroastrian practices known from Persian sources and their local expression in Central Asia.

A Vanished Civilization Remembered

While Panjikent was abandoned after the Arab conquest in the late eighth century, Sanjar-Shah remained inhabited into the ninth century, its palace repurposed by peasant communities. The survival of its wall paintings, despite fire damage and centuries of reuse, makes the site a treasure trove for historians of the Silk Road.

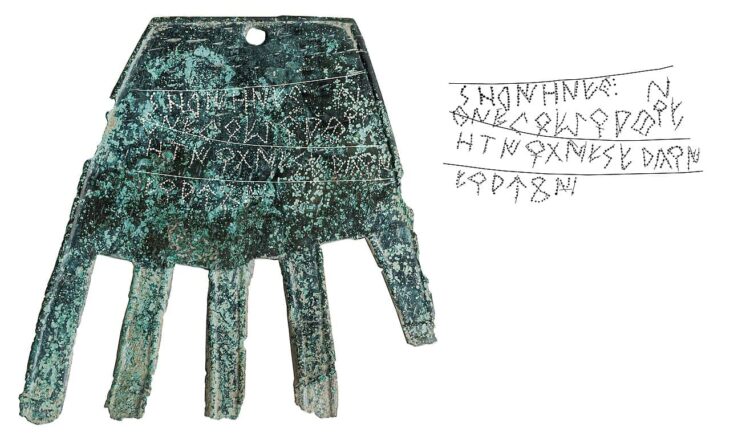

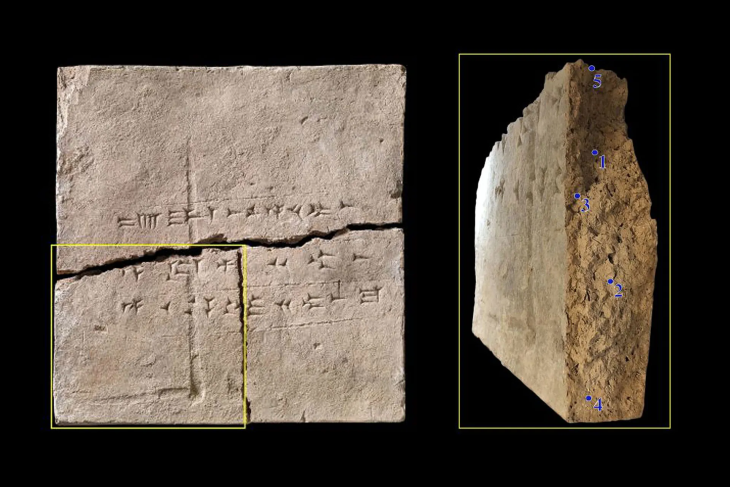

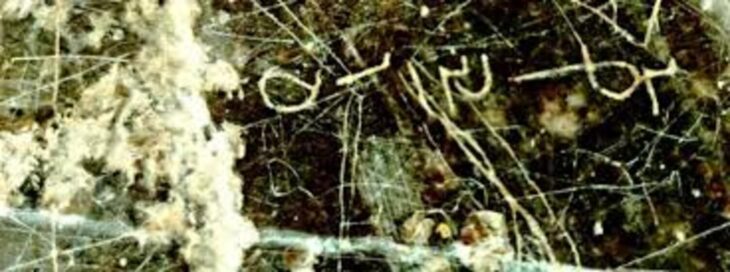

Together with carved wooden panels and inscriptions discovered at the palace, the fresco illustrates Sogdiana’s unique blend of Iranian religious traditions, local artistic styles, and foreign influences brought by merchants and diplomats. Excavations at Sanjar-Shah, supported by the Society for the Exploration of EurAsia, are continuing to reveal how this cosmopolitan culture adapted during the early Islamic period before gradually disappearing as a political power.

Shenkar, M., Kurbanov, S., & Pulotov, A. (2025). A unique scene of fire worship from the late Sogdian palace at Sanjar-Shah. Antiquity, 1–7. doi:10.15184/aqy.2025.10180

Cover Image Credit: Sanjar-Shah Palace, looking east during the excavations. Michael Shenkar